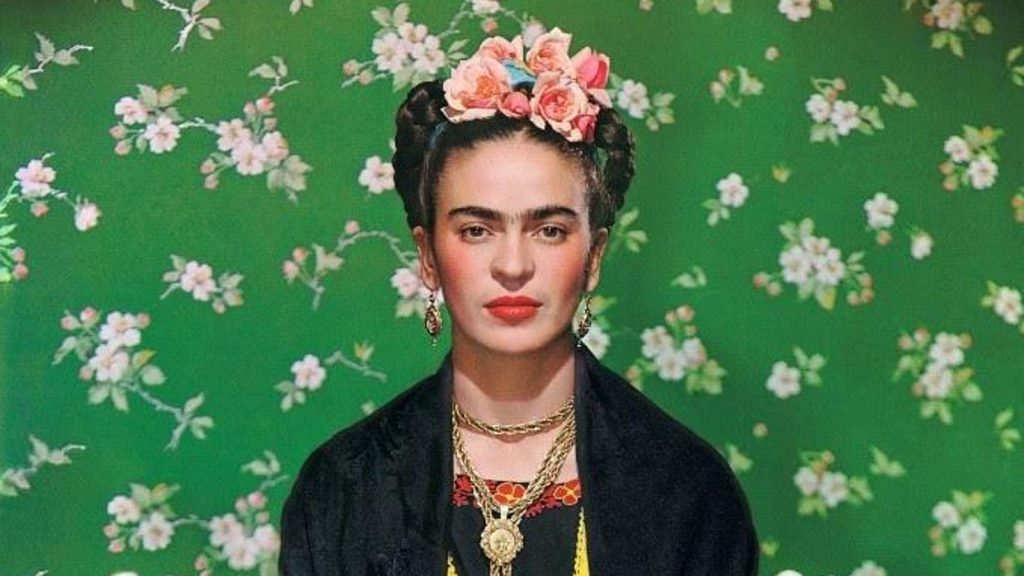

‘Frida on White Bench, New York, 1939,’ Nickolas Muray (American, born Hungary, 1892–1965). Carbon pigment print. Private Collection.

© Nickolas Muray Photo Archives, Licensed by Nickolas Muray Photo Archives

From Norfolk in the east on Chesapeake Bay to Charlottesville in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains to the northwest, Virginia is for art lovers this month. Taking a nod from the state’s iconic tourism slogan–“Virginia is for lovers” was cheeky decades before “what happens in Vegas, stays in Vegas”–art exhibitions currently on view across “Old Dominion” rival those found anywhere in the nation.

Furthermore, with spring sprung and trees blooming across the state, now’s a perfect time to get out and see some art!

Norfolk And Williamsburg

Amador Montes (Mexican, born 1975), ‘Untitled (Soy lo que dibujo),’ 2024. Etching, aquatint, direct acid, and silkscreen Museum purchase, 2024.43.15.

Chrysler Museum of Art

Through May 11, the Chrysler Museum of Art in Norfolk presents “Oaxaca Central: Contemporary Mexican Printmaking,” an exploration of the artistic landscape of Oaxaca, one of Mexico’s most renowned cultural hubs.

“Printmaking in Oaxaca, and across Mexico, has a history stretching back to the 17th century,” Mark Castro, director of curatorial affairs, Chrysler Museum of Art, told Forbes.com. “Over the last 20 years it has taken on new meaning, in part due to the civil unrest that gripped Oaxaca in 2006, when tense labor negotiations between the state government and a local teachers’ union turned violent. In response, the existing printmaking scene got an infusion of artists who wanted to explore the medium’s potential for making their voices heard.”

Printmaking’s roots lie in social protest. In quickly and cheaply disseminating images and messages to the masses. So it was for the printing press going all the way back to Martin Luther and the Protestant Reformation in early 1500s. So it was for Diego Rivera (1886–1957), Jose Clemente Orozco (1883–1949) and David Alfaro Siqueiros (1896–1974)—los tres grandes, or “the three greats,” of Mexican modernism.

“Over the last century, Mexican artists embraced printmaking not only for its creative potential, but for its ability to communicate,” Castro said. “If you are looking to get a message out into the world, prints are an ideal medium. They can be produced in large quantities and are easy to distribute—they’re a form of popular mass communication that predates social media.”

Featuring more than 100 works from the Chrysler Museum’s permanent collection—many recent acquisitions debuting for the first time—”Oaxaca Central” showcases a range of mediums, including woodcut, engraving, etching, lithography, and serigraphy, as well as new approaches that reflect the ingenuity of Oaxaca’s thriving contemporary scene.

Oaxacan artists are pushing the boundaries of printmaking, empowering artists worldwide to approach the medium with fresh perspectives.

“One of the things that struck me about the Oaxacan printmaking workshop was that so many of the artists are working in multiple techniques–they’re not just making a woodcut, they’re combining woodcut with aquatint, silk-screening, etc.,” Castro said. “The openness to learning and combining methods is attracting the attention of a wider array of international artists who are keen to embrace that innovative spirit.”

Castro visited Oaxaca’s printmaking workshops numerous times, meeting with artists to select the works on view in the exhibition. The Chrysler’s interest in Oaxacan prints only began in 2022 following a chance trip to the city made by the museum’s director during which he became inspired and directed staff to start building a collection.

“It’s an incredibly vibrant city in every sense of the word—the buildings are colorful, the food delicious, and you can hear music on the streets,” Castro said. “It’s also one of the epicenters of Mexican cultural history. Being there brings you into contact with a diverse array of people and traditions that make Oaxaca, and really all of Mexico, such a unique place.”

The 45 miles between Norfolk to Williamsburg, VA takes art adventurers from Oaxaca to Rome with the Muscarelle Museum of Art at William & Mary college displaying Sistine Chapel sketches by Michelangelo never before exhibited in the United States. The exhibition was previously reviewed by Forbes.com.

Richmond

Nickolas Muray, Frida with her Pet Eagle, Coyoacán, 1939, printed 2024, inkjet print, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, gift of Nickolas Muray Photo Archives.

© Nickolas Muray Photo Archives

Keep a Mexican state of mind continuing up Interstate 64 another 50 miles from Williamsburg to Richmond where the queen of Mexican art, Frida Kahlo, takes centerstage at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. “Frida: Beyond the Myth” shows off roughly 30 of the icon’s extraordinary paintings, drawings and prints–many rarely seen outside of Mexico–along with supplemental photographs of the artist by internationally renowned photographers and members of her inner circle.

“Frida: Beyond the Myth” explores the defining moments of Kahlo’s life as depicted through her self-portraits, still lifes and works on paper from the beginning of her career in 1926 until her death in 1954. Shown alongside photographs by the friends, family members and fellow artists who knew her best, the exhibition lifts the veil of myth that continues obscuring Kahlo as an individual. Visitors can admire her jewel-like paintings up close while learning about the deeply personal context and traumatic events that inspired her work, thus gaining insight into this remarkable artist who used her creativity to overcome emotional and physical pain.

Throughout her life, Kahlo crafted an opaque, mysterious persona. She claimed to have been born in 1910, the year of the Mexican Revolution, but was in fact born on July 6, 1907, in Coyoacán, a suburb of Mexico City. The bizarre fashion Kahlo portrayed herself in portraits has further had the effect of encouraging admirers to let their imaginations run wild with who she really was, what she really was like. An avalanche of global popular culture attention in the past 30 years, long after her passing, much of it straining reality and breaking from it entirely, has additionally contributed to a Kahlo shrouded more in myth than truth.

It’s a safe bet assuming she would have liked it that way.

Consider it an occupational hazard for the woman who has surpassed Picasso, surpassed Pollock, surpassed Warhol to become the most famous modern artist of all time–at least by facial recognition. Those eyebrows and her colorful clothing adorn tote bags and every other conceivable piece of merchandise from Tokyo to Tanzania.

Kahlo constructed a persona of opposing characteristics: seductive and innocent, strong and vulnerable. She was complex. The world–the art world and otherwise–has always struggled with complex women.

The show takes guests through a closer examination of the events that shaped her life and how she responded to them, progressing chronologically from her early childhood in Mexico, to her tumultuous marriage to Diego Rivera, to her blossoming career between Mexico and the U.S. and, ultimately, to her difficult final years when her health began deteriorating.

Charlottesville

Jody Folwell, ‘Wild West Show, 1996–2003.’ Clay, paint. 21 7/16 x 14 1/16 in. Courtesy of the School of Advanced Research, cat. no. SAR.2004-16-1.

Photo by Addison Doty © Jody Folwell

Continuing to road-trip across the state, 71 miles northwest of Richmond on I-64, art lovers find themselves at the University of Virginia’s Fralin Museum of Art for a presentation as equally rare in these parts as Michelangelo sketches or Kahlo’s paintings. “O’ Powa O’ Meng: The Art and Legacy of Jody Folwell” features 20 works by Jody Folwell (b. 1942) a contemporary potter from Kha’p’o Owingeh (Santa Clara Pueblo, New Mexico).

Folwell revolutionized contemporary Pueblo pottery—and Native art more broadly—by pushing the boundaries of form, content, and design. She is the first Pueblo artist to employ writing and designs as personal, political, and social narratives on her pottery. Radical, daring, brave innovations of an artform and lifeway going back thousands of years.

O’ Powa O’ Meng (“I came here, I got here, I’m still going” in the artist’s Tewa language) displays many of Folwell’s most signature and individual ceramics, including those commenting on the War on Terror and Barak Obama’s election as president, experimentations with theme and style that have no precedent in Pueblo pottery.

From Norfolk to Charlottesville by way of Richmond, and from Oaxaca to Rome by way of Mexico City and Santa Clara Pueblo, Virginia in April reminds us essential global arts destinations aren’t limited to New York and Paris.

More From Forbes