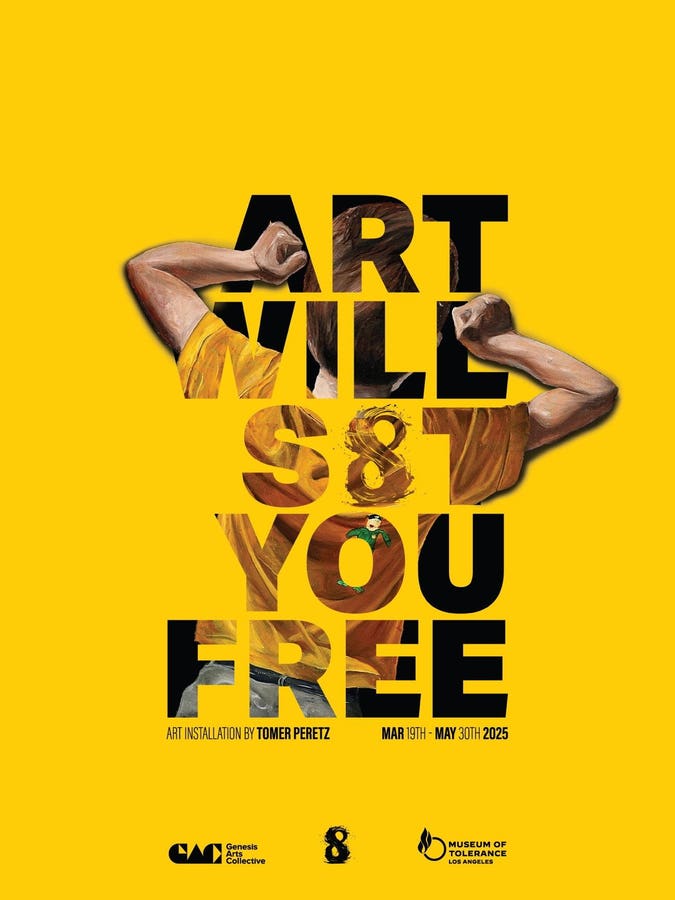

Poster for exhibition Art Will S8t You Free at Museum of Tolerance

Poster by Rotem Fhima, courtesy of Tomer Peretz and Simon Wiesenthal Center Museum of Tolerance

The healing power of art is a phrase one hears a lot, but in a new exhibition, ART WILL S8T YOU FREE, at the Museum of Tolerance in Beverly Hills, one can see art therapy in action, in a collection of eight works that Los Angeles-based Israeli-American artist Tomer Peretz, the first artist in residence at the Museum of Tolerance, made with October 7th survivors and first responders. The exhibition is all the more meaningful because doing so was part of Peretz’s own response to his traumatic experience as a first responder to Kibbutz Be’eri, one of the most murderous sites of the Hamas-led pogrom.

What one sees in the lobby of the museum are eight works made collaboratively with different groups of survivors, orphans, first responders, and frontline soldiers. The museum has also set up an installation of a large canvas that will be painted on site. Also, groups can arrange to visit the museum and collaborate with Tomer and/or his team of artists. Finally, in the space below the lobby, Israeli artist Kalia Gisele Littman, who makes trauma-based art, has an installation combining sound, video, and photography of Tomer and his group of first responders returning to Be’eri.

“The Museum of Tolerance has a longstanding connection to art therapy as a method of exploring and healing human suffering, from the personal anguish of the individual to historic levels of collective trauma,” said Jim Berk, CEO of the Simon Wiesenthal Center’s Museum of Tolerance. “Launching our artist in residence program marks a significant step in expanding the Museum’s mission to educate, inspire and engage global audiences through the power of art. Tomer Peretz’s work exemplifies resilience, healing and the unyielding strength of the human spirit.”

Tomer Peretz

Photo by Michael ‘Mike’ Canon Courtesy of Canon and Tomer Peretz

Play Puzzles & Games on Forbes

Peretz’s own story is one of trauma, creative expression, avoidance, and finding healing and meaning in what he can do for others.

Peretz grew up in South East Jerusalem. His father came to Israel as a child from Morroco and worked as a clerk in a bank; his mother cleaned houses. They lived not far from the Western Wall, in an area surrounded by Arab neighborhoods that he had to traverse each day on his way to school. He was often harassed and got into fights most days.

As a kid, he was always drawing in his notebooks at school, eventually creating murals on his friends’ bedroom walls. He enjoyed creating but didn’t think of himself as an artist. However, he did apply to Bezalel, Israel’s prestigious art academy, but was not accepted.

Peretz entered the military (the IDF) around the time of the Second Intifada (roughly 2000-2005). During this period there were 138 Palestinian suicide bomb attacks, targeting civilians in bars, markets, and public places, sometimes as many as fifteen in one month. Peretz was in the elite Golani Brigade for four years, intensely involved in military operations. Peretz did not disclose where he was or what he did, but it is no secret that during that time Israel launched Operation Defensive Shield, with combat in civilian areas in West Bank cities such as Jenin, Nablus. Bethlehem, Ramallah, Tulkarm and Hebron. 30 Israeli soldiers were killed and 127 were wounded. B’Tselem reported that 240 Palestinians were killed by Israel security forces. For years, Peretz would have flashbacks and PTSD from his military service.

After leaving the military, Peretz, in the tradition of many young Israelis before him, went backpacking across South America. His original plan was to spend 11 months doing so, end up in LA, to work and save money, and then go to India. Wherever he went, he painted on walls. In Argentina and Brazil, he made murals to soccer superstars Maradona and Ceara. Eventually he made his way to LA, spending two years there, before returning to Israel.

However, once back in Israel, Peretz no longer wanted to be part of the existential drama of living there. He’d had enough. He was burned out. He had given his time to the IDF and he was done. He came back to LA which he felt was “the big world. The place where you can really achieve your dreams and do big things.”

Los Angeles then was a place where street art was in full bloom, from Shepard Fairey to Mr. Brainwash, Peretz was aware of their work and even attended Mr. Brainwash’s first show on Melrose in the Fairfax district.

Rather than paint murals in homes or street walls, Peretz decided to go smaller and paint on canvases. He developed what can be called a journalistic or reportorial style, in which he spent extended time with his subjects really getting to know them, in ways that allowed him to tell their story through his portraits. He became a successful artist able to support his wife and children.

Peretz went on to explore photography, videos, even NFTs, expanding the boundaries of his practice. His works expanded on occasion to tell the stories of social challenges or people doing interesting things in far-flung places. Peretz began to travel again, finding new subjects as diverse as his own ascent to the Everest Mountain base camp. For Peretz there were potential portraits subjects everywhere, from his taxi driver in Thailand to a popular Mexican actor whose grandmother lived a simple life in Puebla.

But one place he was disconnected from was Israel. Peretz had made a life in LA. He still brought his family, his wife and three children, back to Israel to see his parents and relatives, and he stayed in touch though social messaging apps with his friends from his former combat unit, but he did not participate in reserve duty. That part of his life had been put away.

More than a year ago, he went to Israel to attend a wedding, accompanied by his two sons, age six and nine. His wife and his daughter stayed in LA. He arrived in Israel on October 2nd, 2023.

Before, Tomer Peretz collaborative painting, 2024 Pastel, Oil, Spray Paint and Markers on Canvas 72″ … More

Courtesy of Tomer Peretz and Museum of Tolerance

October 6th was a Friday, and because it was a holiday weekend (Saturday was Simchat Torah), Tomer had a reunion on the beach in Tel Aviv with members of his former combat unit and their families. It was a great day, a great celebration that went late.

The next morning, beginning at 6:30AM, Peretz’s phone started to go crazy. There were sirens. He went with his children to the bomb shelter and was “trying to explain to my kids what was going on.”

As Peretz began to understand the seriousness of what was occurring, he felt that he needed to do something. He called his military friends, but their phones were not responding (which Peretz understood to mean they were on active duty). Not being part of the IDF reserves he could not show up at a military base to report for duty or even volunteer. So, he began trying aid organizations, offering to do anything he could.

The first to call him back was ZAKA. Having lived through the second intifada, he was very well aware of Zaka, a volunteer group, often made up of Jewish ultra-orthodox men who are paramedics, who go to sites of violence to collect the bodies, or remains of the dead, so they can be identified and buried according to Jewish law.

Peretz dropped off his kids at his parents in Jerusalem and then, early on the morning of October 8th, he was picked up by a group of Zaka volunteers.

At that point, terrorists were still thought to be roaming the South of Israel near Gaza, planning further civilian ambushes, murders and kidnappings. As they were driving South, Peretz imagined that he would end up driving the van, getting them food, or doing some clerical or guard duty to allow the Zaka volunteers to do their work.

They arrived first at the site of the Nova music festival. The Jewish corpses had already been identified the day before. They collected the bodies of the terrorists and delivered those to the Israeli authorities. Their team was then assigned to go to nearby Kibbutz Be’eri.

Peretz was one of the first civilians allowed to enter the kibbutz. There were bodies everywhere. Peretz was asked to pitch in to the team and collect the bodies with them.

As mentioned before, the members of Zaka are most often Ultra-Orthodox. Peretz is not observant, and he is covered with tattoos. So, he felt the other members were watching him and Peretz was hyper-conscious of wanting to do a good job. “I was afraid of being kicked out.”

DURING, collaborative painting by Tomer Peretz, 2024, Pastel, Oil, Spray Paint and Markers on Canvas … More

Courtesy of Tomer Peretz and Museum of Tolerance

Seeing bodies of all ages and types of people, and the way they were left, more than half shot in the head, many with marks of having been tortured, Peretz could not process what he was seeing. Many of the bodies were left in such strange positions – Peretz paused. “I don’t want to get too graphic here.” He focused on the technical aspect of what he had to do in gathering and transporting the bodies. He didn’t allow himself to think or even consider what he was seeing.

Peretz worked with Zaka for five full days, going to his parents’ home each night. Because he would leave early and return late, he barely saw his kids, and didn’t talk to them about what he was doing. He had not told his wife that he was collecting the bodies. But he had taken some pictures of what he saw – the devastation at the Nova site with all the festival detritus, burned out cars, and no people; pictures at Kibbutz Be’eri of bloody mattresses in a children’s room, burned out cars, and the bagged bodies Zaka collected. He posted them on social media. One post read, “Today Zaka pulled out 108 Bodies from Be’eri and there is more.” One of the most affecting posts was a picture of a small garbage bag-like plastic bag that contains a baby’s body. His wife saw the posts and understood what he was doing.

After his work with Zaka, Peretz gathered his sons and returned to LA. At LAX, when he exited customs, and saw his wife and daughter, he collapsed, crying. The airport security had to help him stand.

“From that moment on,” Peretz told me, “I got into a very, very, very heavy depression.” Peretz saw no reason to paint, or work, or even get out of bed. How could he create art, lead a business with partners, when, as Peretz put it, “everything is not important anymore.” He wouldn’t leave his room.He stopped answering the phone.

In the 20 years since he’d left the army, he’d only experienced PTSD flashbacks on three occasions. Now, he experienced flashbacks every hour. His lowest point was when he woke up at 3AM one night, and he was standing in the middle of the street in front of his house with a 9mm gun, guarding it as if he were on patrol.

Peretz understood that he had a problem. He was prescribed all sorts of medications that didn’t work. The only thing that woke him up enough to get out of bed was Adderall, which he took for three months but stopped because he was concerned that he would become addicted.

Tomer’s social media posts about Zaka and the work he did with them at Kibbutz Be’eri made him known not only to various media who wanted to interview him, but also to groups in Israel working with Oct 7 survivors and families.

It was only a few months after October 7, when Peretz was contacted about a group of 120 Nova survivors, relatives of the hostages and Israeli first responders, who were coming to Los Angeles.

The Future, collaborative painting by Tomer Peretz, 2024, Pastel, Oil, Spray Paint and Markers on … More

Courtesy of Tomer Peretz and Museum of Tolerance

Peretz decided that he would do an art project with them. He gave the group, who were not artists and had no art training, free reign to write, draw, color, however they wanted on a large canvas. They actually filled up three canvases. Afterward, Peretz added some of his own narrative artistic flourishes, such as large letters saying “The Light Will Win” that seems to emerge from the canvases.

For the first time, since October 7, what Peretz was doing had meaning. Rather than dwelling on his interior state, he was helping and guiding others. “Instead of going in, I was going out,” he said. He had found his reason for being and how to put his artistic talents in the service of others, which had a tremendous healing impact on him.

Sweats. collaborative work by Tomer Peretz, at Museum of Tolerance.

Courtesy of Tomer Peretz and Museum of Tolerance, Photo by Linda Kasian Photography

Since then, Peretz has done nothing but host group after group for art projects, work that has become art therapy (with professionals consulting on the project). Some of the projects are whimsical: Since many of the victims and hostages were wearing sweatpants, Tomer has made sweatpants decorated by the art groups, giant versions of which have been displayed on buildings calling attention to the hostages’ plight.

Zaka. collaborative painting by Tomer Peretz, 2924

Courtesy of Tomer Peretz and Museum of Tolerance Photo by Linda Kasian Photography

Peretz has made art with a troop of soldiers who served more than 200 days in Gaza and 70 in Lebanon. They came to LA for vacation because one of them lives here. They had never held a paintbrush and had not been allowed to express themselves. Names float across the canvas with diagrams of areas of battle and an exploded car, and in the center there is a powerful image of a clenched fist, and nearby the words “wanting to kill our compassion.” Another was made by Tomer and his Zaka team, on which Tomer painted the image of a woman as he found her lying in a strange position but now she seems to be floating. Another group was a special camp for kids, ages 9-14, who October 7 made orphans. Peretz asked them to draw superheroes – many drew Superman but some drew their siblings or their parents who were murdered.

Kalia Gisele Littman

Courtesy of the artist

As word spread of what Peretz had been through and what he was doing now, he was contacted by Kalia Gisele Littman, an Israeli documentarian and photographer who wanted to make a work about his Zaka unit. “I create art from trauma,” she told me recently. Littman had experienced severe burns as an 8 year old. For her, “Part of my healing was going back to the place of my trauma and revealing for the first time my scars.”

Zaka team installation by Kalia Gisele Littman

Photo by Linda Kasian Photography, Courtesy of the artist

asked Tomer and his Zaka unit to return to Kibbutz Be’eri almost a year after they had been there. “We went back to those houses [where] we picked up the bodies,” Tomer said. “It was so therapeutic for us. It helped us so much to deal with the pain.” She photographed each team member in the ruins of a house that had belonged to a 94 year old Jewish Kibbutz resident, taken hostage on October 7, who escaped by throwing himself out of a moving car as they were driving back to Gaza. His home in Be’eri was one of the few where there were no dead bodies for Zaka collect. In photographing them there, Littman said, “What I wanted to bring is hope. I wanted to bring their resilience because I felt like one year after, what we need is strength.”

Installation view of collaborative art wall at ART WILL S8T YOU FREE exhibition at Museum of … More

Photo by Linda Kasian Photography, Courtesy of the artists

On the floor below Tomer’s exhibit is an installation by Littman. Presented in a circular enclosure, along with video and the sounds of nature that Littman recorded at the Kibbutz when they returned, one hears the sounds of the natural world going on, interspersed with an official loudspeaker warning that aired in the Kibbutz on October 12, telling survivors to come out of hiding while alerting them that terrorists were still at large.

Peretz said that in Israel he also met with some Holocaust survivors, some of whom are artists and that doing so was a conversation about “How can you live with this for the rest of y our life. How can you create a colorful life, a good life in spite of all the memories?”

Peretz once again feels deeply connected to Israel. “As a Jewish artist, I was never naïve about the harsh realities of collective trauma from war and violence, but there’s no question my experience on October 7 and every day after has profoundly affected my transformation as a human and an artist,” said Peretz. “ART WILL S8T YOU FREE is intended to create a secure and nurturing environment for groups and survivors of terror attacks to explore their emotions and embark on their healing journey.”

ART WILL S8T YOU FREE is presented by the Museum of Tolerance in partnership with The Genesis Arts Collective and The 8 Foundation. For tickets and more information click here.