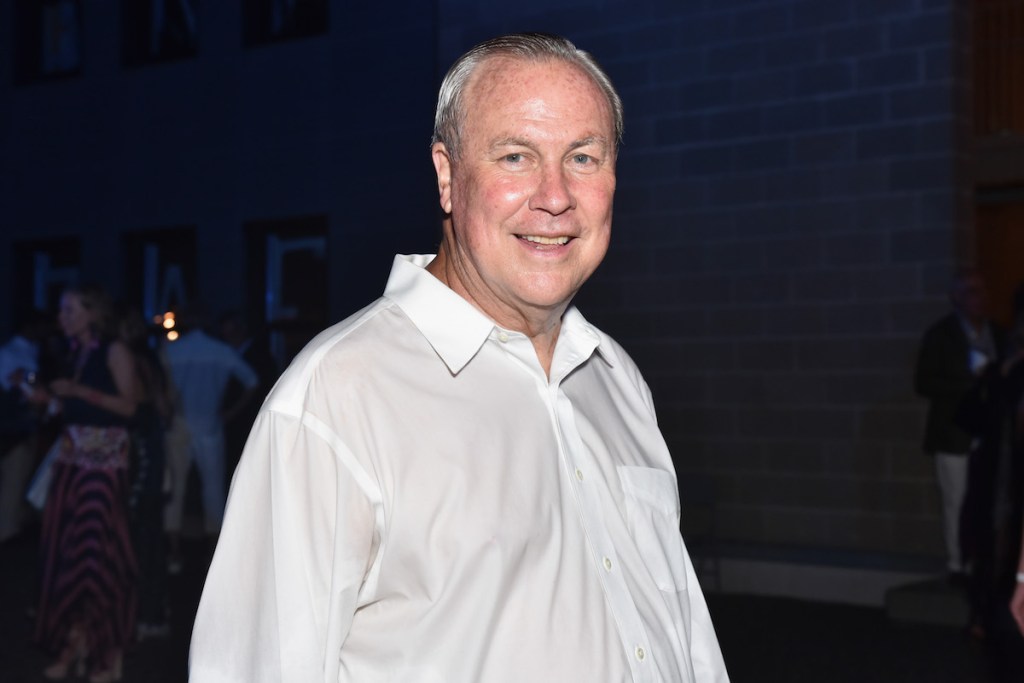

Robert Wilson, a playwright and artist who cultivated a loyal following in the art world for spare productions that bridged the gap between performance art and theater, died on Thursday in Water Mill, New York, at 83. His death was announced by the Watermill Center, the arts center he founded there, which said he died of a brief but acute illness.

“While facing his diagnosis with clear eyes and determination, he still felt compelled to keep working and creating right up until the very end,” the arts center wrote in its announcement. “His works for the stage, on paper, sculptures and video portraits, as well as The Watermill Center, will endure as Robert Wilson’s artistic legacy.”

Related Articles

Wilson’s work ran the gamut from artworks shown in museums to unconventional stage adaptations premiered in theaters. Much of his work was characterized by an interest in stillness and slowness, qualities that could be found in both his durational performances and his art.

One widely seen series of videos, for example, was meant to act as portraits of its subjects: the singer Lady Gaga taking up the pose of Mademoiselle Caroline Rivière in a famed 1806 Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres painting; the actor Brad Pitt standing in a pair of thin white shorts in a room lit blue; the artist Pope.L lounging a model of a treed landscape, his skin turned silver. Each of these videos runs around three minutes, though little happens during that span, which was exactly Wilson’s point—to make viewers notice things that may otherwise go unnoticed.

“If you slow things down, you notice things you hadn’t seen before,” Wilson once told the critic Hilton Als, who profiled him for the New Yorker in 2012.

Wilson broke new ground in 1976 with his production of Einstein on the Beach, an opera about that tells the biography of Albert Einstein in only the loosest sense, his life narrated abstractly via music by Philip Glass and choreography by Lucinda Childs, who co-authored the libretto with Christopher Knowles and Samuel H. Johnson. Though the opera is nearly five hours long, it contains minimal dialogue and generally functions more like a piece of performance art, with audience members permitted to enter and exit at will.

The opera was perceived almost immediately as a provocation. “A great deal of this is boring,” wrote Clive Barnes in the New York Times. “But it was Logan Pearsall Smith, at the beginning of century, who pointed out that boredom taken to its ultimate degree becomes, in itself, species of art. And Mr. Wilson uses theatrical boredom just as Mr. Glass uses his electric organ. They know that, once in a while, it is nice when they stop.”

Now, the opera has become a classic. Many other major theatrical productions by Wilson have followed, including one centering around the life of performance artist Marina Abramović.

For Wilson, much of his work was deeply related to his background in art. He said he saw no division between art in the traditional sense and theater, something evident in the programming for the Watermill Center, which he founded in 1992.

“What interests me about theater is that it brings together all the arts,” Wilson said in a recent interview conducted by Hauser & Wirth gallery. “It’s architecture, painting, light, poetry, dance, music and philosophy. All the arts can be found in what we call ‘theater.’ In the Latin sense of the word, ancient theater was ‘opus,’ meaning all inclusive. My early works were called silent operas. And in a sense, they were ‘opera’ in the Latin sense of the word, in that they were all-inclusive works.”

This obituary will be updated.