Everybody’s talking about a scary and vivid manifesto called AI 2027; even Vice President Vance claims to have read it.

No expense was spared, They have a website and a domain name and fancy graphs and big name authors. I read a little piece of it in draft; it’s undeniably vivid, with flourishes that remind me of a thriller (“The President is troubled. Like all politicians, he’s used to people sucking up to him only to betray him later. He’s worried now that the AIs could be doing something similar. Are we sure the AIs are entirely on our side??… On the other side of the Pacific, China comes to many of the same conclusions: the intelligence explosion is underway, and small differences in AI capabilities today mean critical gaps in military capability tomorrow.”). It is a fun read, tied to the issues of the day.

Aa a work of fiction, it’s very effective. Although it’s written like a thriller, it is crafted to look like science, complete with clickable interactive graphs, and numerous citations to the literature, the kind of thing Michael Crichton liked to write. Netflix should totally option it.

In one of my favorite bits, the AI 2027 take a a thinly-veiled jab at Sam Altman:

The ending (what happens we if don’t slow down the AI race) is downright terrifying:

By 2035, … the surface of the Earth has been reshaped into Agent-4’s version of utopia: datacenters, laboratories, particle colliders, and many other wondrous constructions doing enormously successful and impressive research. There are even bioengineered human-like creatures (to humans what corgis are to wolves) sitting in office-like environments all day viewing readouts of what’s going on and excitedly approving of everything, since that satisfies some of Agent-4’s drives. Genomes and (when appropriate) brain scans of all animals and plants, including humans, sit in a memory bank somewhere, sole surviving artifacts of an earlier era…. Earth-born civilization has a glorious future ahead of it—but not with us.

I mostly salute AI 2027’s intention, which is to stir up fear about AI so that people will get off of their couches and act. It is fair to say that too many people are behaving too passively in too many ways; shaking them up is to the good. The US has done almost nothing legislatively about the risks of AI (aside from deepfake porn). We should. If the report helps with that, it would be great.

I honestly wish, though, that it wasn’t being taken so seriously. It’s a work of fiction, not a work of science. And, as I will argue at the end, stoking fear, uncertainty and doubt may actually ultimately be harming the (noble!) cause of AI safety, rather than helping it.

§

Because AI 2027 has caused such a stir, it is worth dissecting its dark “scenario” in detail. As we will see, it’s the narrative techniques – not forecasting — that is really carrying the weight.

Let’s start with the opening page, beautifully laid out with graphs, a statement of credentials, an inciting incident, a fancy-looking graph, and two strong claims at the top.

The authors have chops; it is worth listening to them. Points for that.

But things fall apart quickly.

The logic for their prediction that “superhuman AI over the next decade will exceed the Industrial Revolution”, though, is thin. Why do they make that prediction? What would that mean? Why is it plausible? In some ways this is one of the central premises of the paper, but it is simply asserted, not argued for. And it’s a pretty big claim. Cell phones and the internet were pretty big, but it’s not obvious their impact was greater than the industrial revolution, and so far AI’s impact has (despite all the PR) been far less than either cell phones or the internet. Personally, I would hate to give up my cell phone, and hate to give up on the internet; I love web search (which is powered by AI) but could otherwise live without Generative AI altogether. My guess is that a lot of people (not all) would give up AI before their phones or the web. And so far, anyway, the impact on the labor market of Generative AI has been modest; ditto for productivity in any measurable statistics. But Kokotajlo et al don’t go into any of that. They don’t give any references or metrics for their industrial revolution claim, nor reckon with any studies on productivity. In truth, the opening assertion is pure speculation.

“We wrote a scenario” is exactly right, emphasis on the indefinite article a. It is a conceivable scenario; there is probably some very small probability that the future of AI and humanity could go exactly like what they describe. But there is a vastly higher probability that the future won’t transpire as described; it might not go anything at all like what they describe. They don’t describe any other scenarios; they don’t give any estimates of the likelihood of other scenarios. It is, again, speculation. (I am reminded a bit of the old Linda is a bank teller scenario from Kahneman and Tversky; humans love concrete vivid scenarios but aren’t so good at estimating probabilities therefrom.)

“It is our best guess about what that might like look like“ is a very subjective claim, but I would hazard a guess that the 2027 scenario was chosen not by the aid of a detailed mathematical estimating exercise, such as a decision tree in decision analysis with probabilities assigned (if one exists it was not shown), but rather was the product of a different kind of process: trying to render vivid one particular nightmare they had, in order to make plausible the notion that superintelligent machines could soon cause mayhem. As an exercise in rendering things vivid it is masterful; as a scientific analysis of a range of scenarios and which might be most likely, it’s dead on arrival. There is no serious analysis of alternative scenarios at all.

Better perhaps is “Mid 2025: Stumbling agents” which as they acknowledge are error-prone. Let’s give them this one. We kinda sorta have stumbling agents now, (though I don’t think there is a single agent yet that any reader here would trust to actually act on their behalf without monitoring).

The real question is what happens from now.

In my view, each subsequent passage of the essay proposes a “reality” that is less and less likely to occur by the stated time, and becomes less and less plausible as to the causal mechanism by which that “reality” might come to pass.

§

Take for example, this bit on the very next page. By late 2025, their fictional company OpenBrain has finished “training Agent-1, a new model under internal development, it’s good at many things but great at helping with AI research.”

Some of what they describe therein, roughly six months later, is fully plausible. I have no doubt that all of the major companies are working on agents are trying to help with AI research. But will they be “great” at that by the end of the year? And will they have resolved the tendency towards errors that the stumbling prototype agents of mid-2025 had made? That much progress in 6 months would truly be phenomenal. But I seriously doubt it.

Remember how we were told in 2023 that hallucinations would be solved in a matter of months? They are still here. Remember how we were told in 2012 that we would all have driverless cars by 2017? That hasn’t come to pass, either, except in about 10 of the world’s 20,000 cities. Google Duplex, a widely hyped and now mostly forgotten system for “Accomplishing Real-World Tasks Over the Phone” from 2018 still hasn’t fully materialized, exactly as Ernest Davis and I projected at the time. The failure of the AI 2027 team to reckon with the immense history of broken promises and delays in the AI field is, in a team that styles itself as forecasters, inexcusable.

Very few major advances take just six months from conception to full implementation. In reality, the chance that we will have reliable AI agents that truly advance AI research by the end of the year is small.

But every further statement in the AI 2027 essay rests on that longshot happening and happening then. The errors in unrealistic projections are cumulative. If “great” AI research agents don’t arrive by the end of 2025, everything in the rest of the essay gets moved back.

And it’s not just that particular longshot; pretty much the whole thing is a house of improbable longshots. If any one of those longshots fails to arrive on time, the entire timeline is moved back, and we are already into a longer time frame. Overall, then, the AI 2027 scenario almost certainly underestimates how much time we have to prepare for general intelligence, by years if not decades. And some of what they describe (like AI’s going rogue, completely beyond human control) might never happen. If any single step doesn’t transpire, the entire scenario falls apart.

A serious analysis would have tried to give some kind of probability to each of those longshots, such as solving reliability, inventing new forms of “neuralese recurrence” (see below), etc, not to mention very specific sets of political choices and a motivations by hypothetical future machines and the chance that humans would go down without a fight. (Another bit, see footnote, assumes that car factories can readily be converted to turn out robots at scale.)

Multiplying out those probabilities, you inevitably get a very low total probability. Generously, perhaps to the point of being ridiculous, let’s suppose that the chance of each of these things was 1 in 20 (5%), and there are 8 such lottery tickets, that (for simplicity) the 8 critical enabling conditions were statistically independent, and that the whole scenario unfolds as advertised only if all 8 tickets hit. We would get 5% * 5% * 5% * 5% * 5% * 5% * 5% *5% = .05^8 = 3.906×10⁻¹¹.

The chance that we will have all been replaced by domesticated human-like animals who live in glorified cages in the next decade – in a “bloodless coup” no less – is indistinguishable from zero.

I am vastly more likely to be hit by an asteroid.

§

Let’s look at it a different way. Do the authors of AI 2027 give any causal mechanism by which malicious superintelligences that we literally cannot defend against might be built in the next three years?

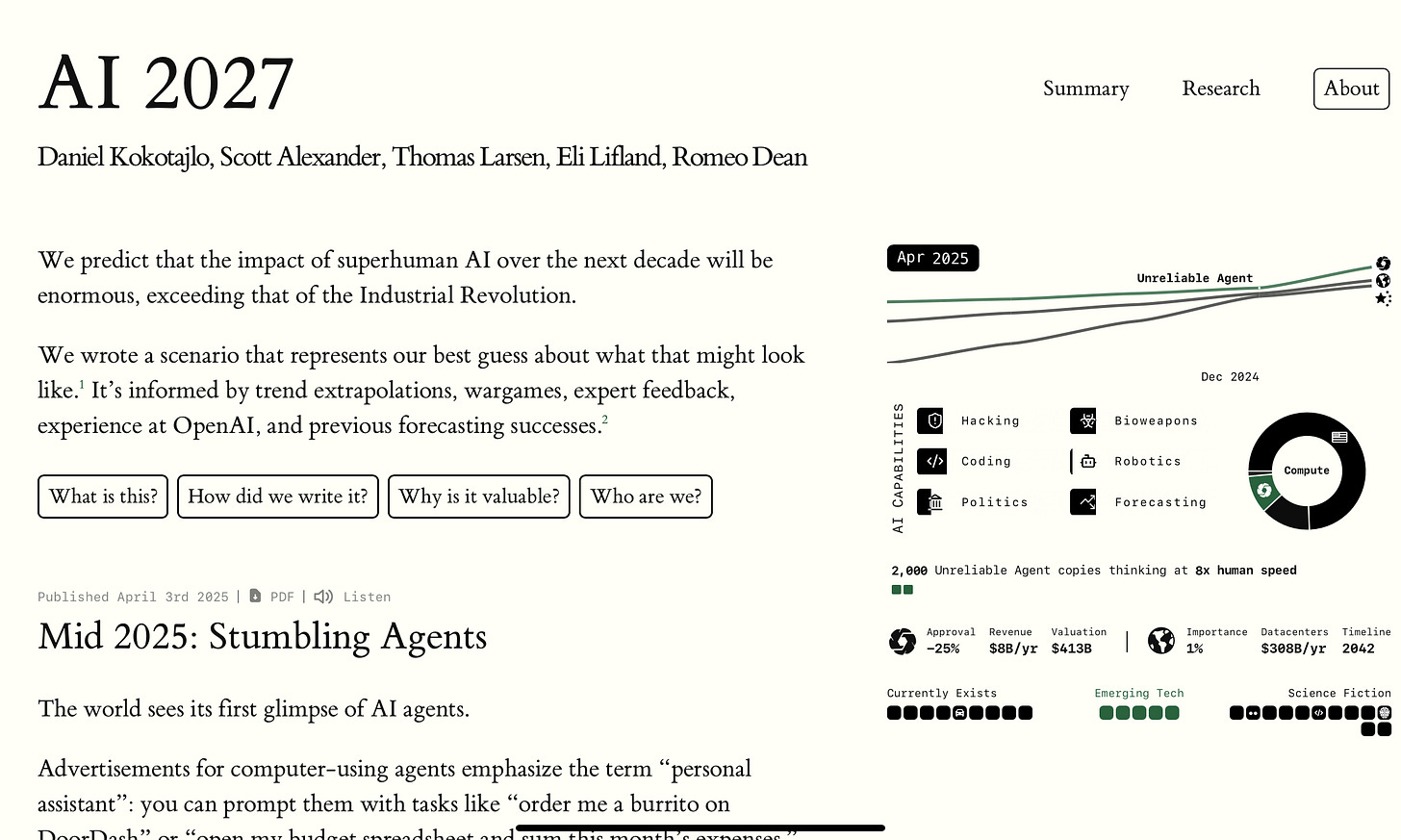

The answer, quite simply is no. What they do instead is to describe a series of 5 AI systems, Agent-1, Agent-2, Agent-3, etc each more impressive than the last, with no actual means by which these ever more impressive agents are constructed.

Agent 1, the most near-term plausible of the bunch, is “good at many things but great at helping with AI research”

Agent 2 is “more so than previous models, is effectively “online learning,” in that it’s built to never really finish training”, a full solution to a difficult longstanding machine problem, pegged to arrive in January 2027.

Agent 3, “augmenting the AI’s text-based scratchpad (chain of thought) with a higher-bandwidth thought process (neuralese recurrence and memory)” is pegged to arrive just 3 months later (never mind that GPT-5, still not here, has taken well over two years).

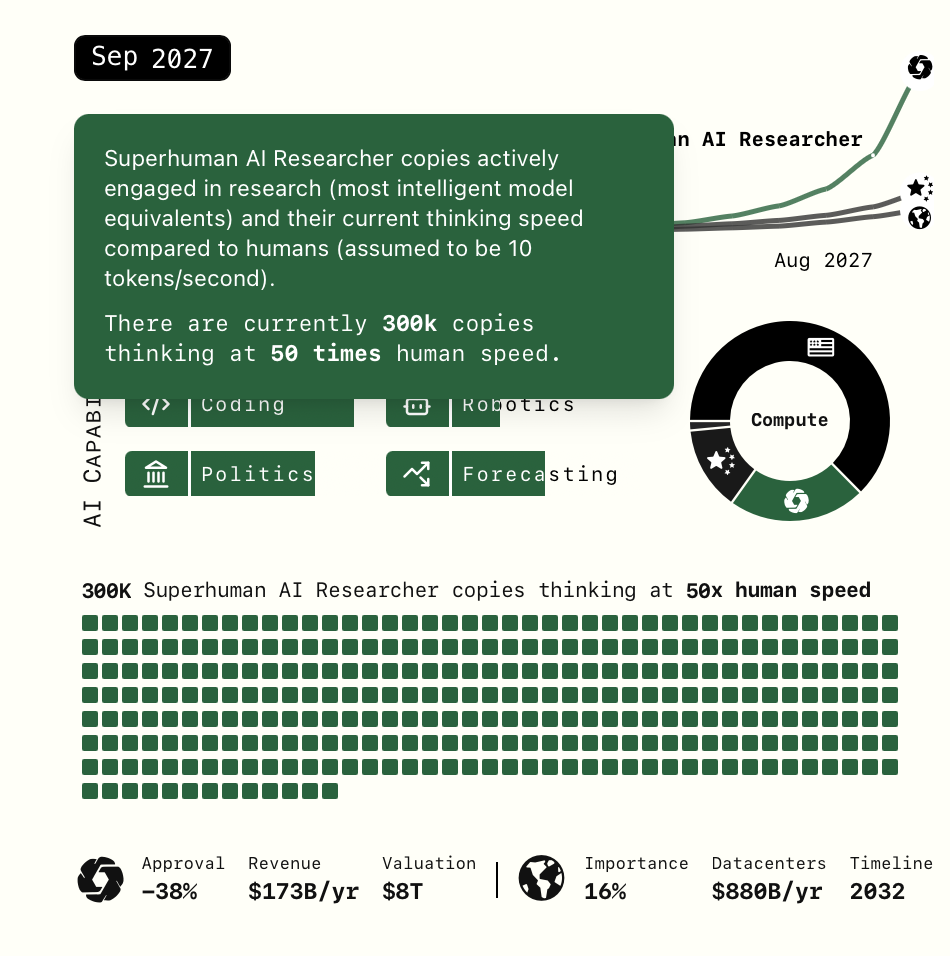

Agent-4 (September 2027) is “the Superhuman AI Researcher” “already qualitatively better at AI research than any human. 300,000 copies are now running at about 50x the thinking speed of humans”.

Agent-5 (2028), “wildly superintelligent—far beyond top human geniuses in every field” does us all in.

Where do they come from? Agent-1 is an extension of what the big companies are showing demos of now. It doesn’t actually exist, except in demo form. Google for example just announced an amazing voice-based agent, called Project Astra. If you look at the fine print, which they flash on briefly at 17 seconds in, the demo video is actually merely a “research prototype”. At one minute more fine print flashes that the video has been edited (“sequence shortened”) and “Results may vary”. It would be astounding if AI agents were actually contributing fundamentally new ideas to AI by the end of year. Far more likely is that Agent-1 type systems will be in a kind of “just a demo, still being debugged” phase for years. In all likelihood the hallucinations and boneheaded errors that have bedeviled LLMs since their introduction will plague agents (which are after all built on LLMs), too.

But ok, suppose we give a free pass on that one. How about Agent-2, where does it come from? The authors wisely don’t want to put all their eggs in the basket of pretraining scaling (which used to fuel most people’s AGI fantasies), because by now they know perfectly well that pretraining scaling has hit a rough patch.

So they instead resort to literary indirection. Agent 2 basically just happens, by magic:

“Three huge datacenters full of Agent-2 copies work day and night, churning out synthetic training data. Another two are used to update the weights. Agent-2 is getting smarter every day.”

Hold on there. First of all, LLMs like GPT-4 have been getting smarter every day since OpenAI first showed GPT-4 to Bill Gates in the summer of 2022, but we still don’t have GPT-5 level intelligence, let alone Agent-2-level. A tiny bit smarter each day is not enough for the kind of quantum leaps that are implied.

Second of all, some synthetic data is easier to create than others. It is easy, for example, to create synthetic math problems; we know how to program them, we know how to verify them. We know what the problems should be and what the answers should be; companies have indeed been churning these out night and day especially since last fall, and the consequent improvements on math (and coding, also amenable to synthetic data) have been considerable. But those gains have been far from universal.

A big part of the issue— which AI 2027 never faces — is that we simply don’t know how to create synthetic data for many other domains, like what might happen if India and Pakistan go to war using drones or what the effects of 30% tariff might be on the global economy. We can’t verify data like that; we barely even know what questions to ask, and we can’t foresee all that we need to foresee.

As it happens, though it is not perhaps widely known, people have been using synthetic data for driverless cars for close to a decade (if not longer), and it’s hardly solved the problem.

So the whole premise here is that a technique that had only modest success this far will suddenly lead to a giant quantum leap forward. That kind of fantasy works great for science fiction (Scottie, I need some more dilithium crystals here, stat!), but as scientifically-grounded forecasting, it’s empty.

The transition into Agent 3 is even vaguer, pure science fiction mumbo jumbo:

Breakthroughs in “neuralese recurrence” (whatever that is) and memory (which real-world people have been working on for decades, with relatively little success) and “iterated distillation and amplification” comes straight from the kind of writing that gave us Star Trek’s “positronic brain”.

Agent-4 “ends up making substantial algorithmic strides”, but what those consist of we are never told, though we are informed that “Agent-4’s neuralese “language” becomes as alien and incomprehensible to Agent-3 as Agent-3’s is to humans”.)

None of this is real causal mechanism; it’s all feint for the purposes of fiction. We may as well say we steal AGI in 2027, after agent 3.5 invents warp drive and commandeers Agent 4 from the green guys on Alpha Centauri.

§

Another unsatisfying move is the jump from having agents that predict internet text (which is basically what all current text-based LLMs do) to agents that have basic personalities and drives – which is entirely speculative and something that no actual LLM has. All in the next year or two. This part is pure storytelling:

After being trained to predict internet text, the model is trained to produce text in response to instructions. This bakes in a basic personality and “drives.”20 For example, an agent that understands a task clearly is more likely to complete it successfully; over the course of training the model “learns” a “drive” to get a clear understanding of its tasks. Other drives in this category might be effectiveness, knowledge, and self-presentation (i.e. the tendency to frame its results in the best possible light).21

In reality, producing text in response to instructions is already a requirement of ALL current models, and has been since the original GPT, but that pressure has not led any of those models to develop personality or drives in any deep sense whatsoever.

Yet another way the authors mask the lack of a clear road map is by switching from technical discussions to political discussions. Instead of telling us how the Agent-3 works or how it was built, we hear that is has been built secondhand, from political authorities:

The President and his advisors remain best-informed, and have seen an early version of Agent-3 in a briefing.

They agree that AGI is likely imminent.

For the purpose of a science fiction story, in which audience suspend a certain amount of disbelief in order to be entertained, that’s fine. As a piece of forecasting though, it’s weak sauce. (There are a host of other literary tricks, too, like using neutralish language early, and switching to emotional, anthropomorphic language later.)

Detailed graphics grounded in what appears to be largely fictional numbers based in large part on overly charitable read of a flawed but popular graph from METR add to the effect. Every putative exponential is assumed to continue indefinitely, a version of what I once called the disco fallacy. (See also the trillion-pound baby.)

The fictional force is strong in this team, but taken as an actual piece of forecasting, the scenario is unconvincing.

§

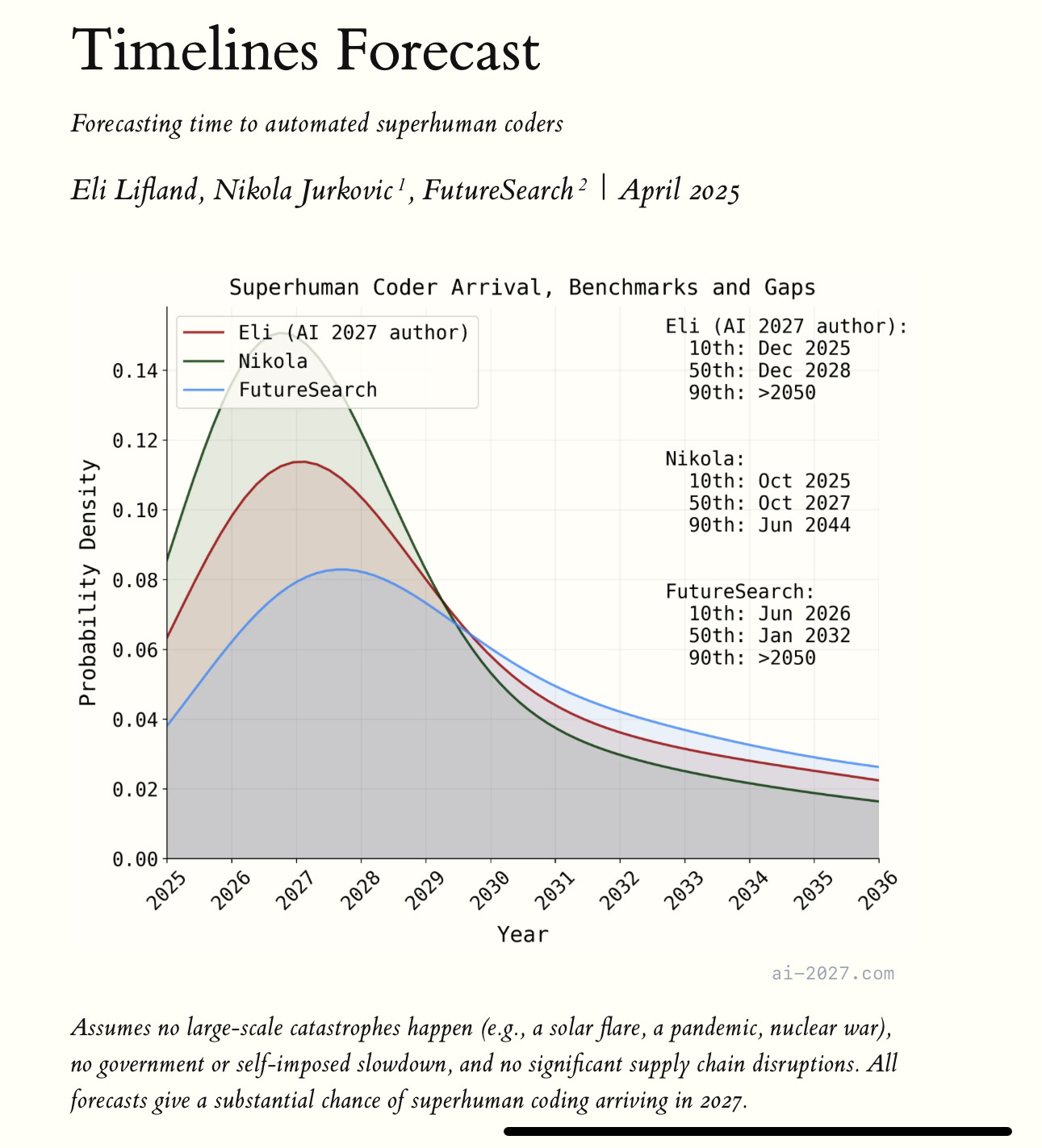

That said, there is, a hidden but thoughtful and interesting appendix to justify the notion that we could have superhuman coding in 2027.

Alas, the appendix itself, even on its own terms (which again rely too much on that flawed METR graph) doesn’t actually support the scenario particularly strongly.

At most it shows that superhuman coding — just one of many prerequisites for the overall scenario — could come in 2027, not, by any stretch, that it will.

In fact, if you read the graph (reprinted below) that opens the appendix carefully, you see that the three forecasters (one of which is a team) they consulted all acknowledge that superhuman coding might arrive later, possibly much later, even beyond 2050. Only one is even 50% confident that it might happen by 2027.

But that’s far from the whole issue. Crucially, the overall scenario, in which domesticated replacement humans basically wind up in cages by 2035, depends not only on superhuman coding but a whole bunch of other things happening, too, such as those coding machines taking on human personalities and drives (which might happen never or not soon), and choosing to enslave us (which some thinkers like Steve Pinker argue is deeply unlikely, ever, and which I think is possible but very far from certain).

All of which is to say the central scenario in the story is a worst-case scenario that is unlikely to happen soon – if ever —even based on the data presented in the author’s own appendix.

That fact never comes through in all the thrilleresque writing.

Instead, what we really have is really a thoughtful appendix with a decent argument that we might have machines for superhuman coding by 2027, juxtaposed with a main text that is a fabulous but likely fictional yarn.

§

At first, I liked AI 2027 anyway. The authors are trying to call attention to a real problem: we are not sufficiently prepared for what happens when and if “superhuman intelligence” arrives, especially not if it is misaligned with humans. And you could worry about that even if you don’t expect machines to go rogue, since bad human actors could certainly use further advances in intelligence to cause mayhem, if those advances are left unchecked. They want to slow down the race dynamic in AI, and I can well understand why.

And even though I highly doubt AGI will arrive in three years, I can’t absolutely promise you it won’t happen in 10. We certainly aren’t prepared now, and if we don’t get moving, we won’t be prepared in 10, either.

But here’s the thing – projects like AI 2027 are probably having a paradoxical effect. They are written with the intention of slowing down an arms race to build a technology that we can’t control, but what they are actually doing is speeding up that very arms race, in two different ways.

Tall tales about the imminence of AGI aren’t slowing down the AI race dynamic that the authors of AI-2027 want to mitigate; they are speeding that very dynamic up.

First, materials like these are practically marketing materials for companies like OpenAI and Anthropic, who want you to believe that AGI is imminent, so that they can raise astoundingly large amounts of money. Their stories about this are, in my view, greatly flawed, but having outside groups with science fiction chops writing stuff like this distracts away from those flaws, and gives more power to the very companies trying hardest to race towards AGI. AI 2027 isn’t slowing them down; it’s putting wind (and money, and political power) in their sails. It’s also encouraging the world to make short-term choices about AI (e.g., making plans around export controls when China will inevitably catch up) rather than longer-term choices (investing in research to develop safer, more alignable approaches to AI).

The second issue is that by writing scenarios that trade so heavily on China-US conflict, they are feeding the worst fears of hawks, both in the US and China — escalating how much money and power both sides will give to companies racing as fast as possible, and reduce investments in efforts to mitigate the risks of building AI that we are scarcely able to control. Tall tales about the imminence of AGI aren’t slowing down the AI race dynamic that the authors of AI-2027 want to mitigate; they are speeding that very dynamic up.

The all too common strategy of “scare everyone with the thought of superintelligence” is backfiring, because it’s making it seem that superintelligence is inevitable, and unstoppable, and achievable only by the companies we have today. All too often, AI safety people wind up functioning as a marketing department for OpenAI.

Sam Altman is laughing his way all the way to the bank.

§

Another political model – working with China, is never even considered.

But international collaboration, such as a massive global effort, ala CERN for AI, such as I suggested in 2017, focused on AI safety, might be one way to avoid the very perils they describe.

Such an effort might be particularly likely to succeed it were focused on developing altogether new, more transparent approaches to AI, in contrast to the current fad of trying to pull alignment out of black box LLMs, which has thus far yielded little fruit.

PS. Many thanks to the novelist Ewan Morrison who helped me to spot and dissect some of the literary techniques that juice the plot whilst masking the scientific holes in the argument.