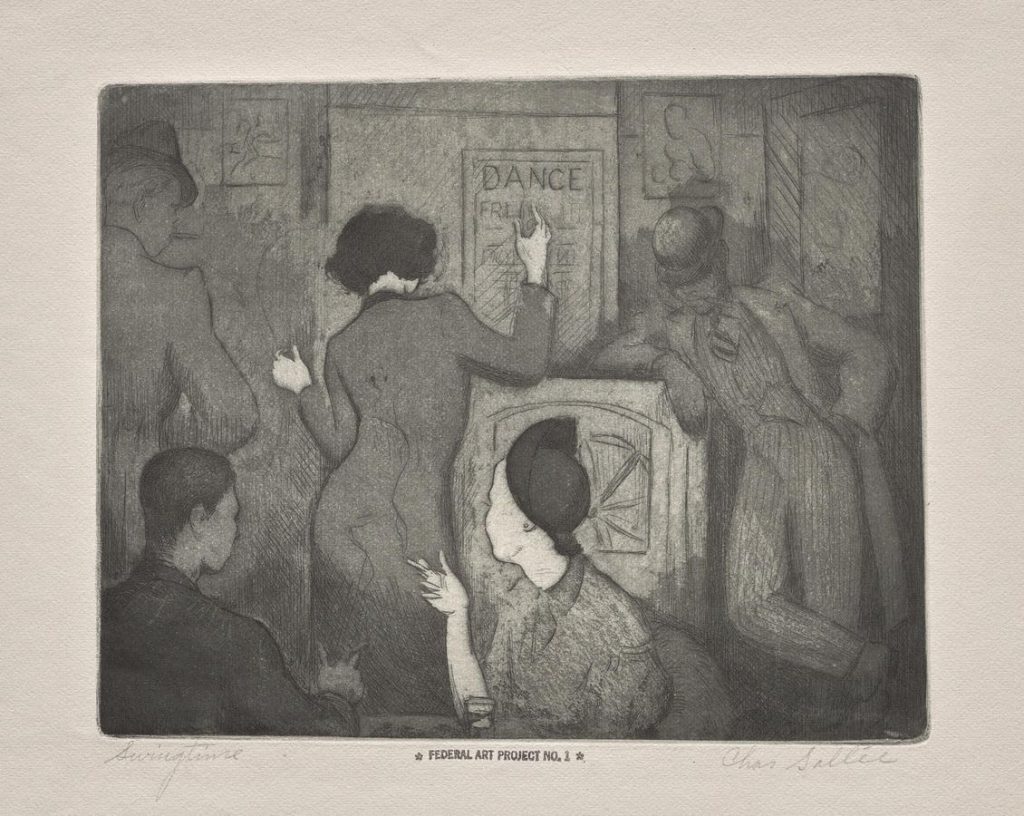

‘Swingtime,’ c. 1938 . Charles Sallée (American, 1911 – 2006). Etching and aquatint; image: 14 x 17.4 cm; sheet: 25.2 x 33.2 cm. The Cleveland Museum of Art, Created by the Federal Art Project, Works Progress Administration, and lent by the Fine Arts Collection of the US General Services Administration, 4215.1942.

The Cleveland Museum of Art

The popular history of Black art in America in the early and mid-20th century has been reduced to production emanating from a handful of epicenters–Harlem, Chicago, D.C., etc.–along with mostly self-taught “folk” artists out in the countryside, places like Gee’s Bend, AL.

In the same way important soul music was produced beyond Detroit, Memphis, and Philly, in places like Cincinnati, hotspots for African American visual arts existed in places like Louisville and Nashville and Cleveland. Those locations previously omitted from the story are finally being returned to it.

At the Cleveland Museum of Art, “Karamu Artists Inc.: Printmaking, Race, and Community,” highlights the role of printmaking at Cleveland’s Karamu House, one of the best-known sites for Black American culture since opening in 1915. Initially founded as a settlement house by Russell and Rowena Jelliffe, “an integrated community center dedicated to fostering human relations through the arts and humanities,” Karamu House soon became known for using the arts as a means of encouraging racial integration. The Jelliffe’s, a white couple, were gender and racial equity activists and philanthropists, along with supporters of the arts and education in Cleveland throughout the 20th century.

Although mostly noted today for its premier theater program, Karamu House birthed a printmaking workshop beginning in the 1930s where artists and community members alike—including a young Langston Hughes—could experiment with various techniques, playing on printmaking’s fundamental accessibility and democracy. This exploration led to the formation of Karamu Artists Inc. in 1940, a group counting some of the most recognized Black printmakers of the Works Progress Administration era as members: Elmer W. Brown (1909–1971), Hughie Lee-Smith (1915–1999), Charles Sallée (1913–1906), and William E. Smith (1913–1997).

“What was going on here in Cleveland during the 30s and 40s was just as important and substantive and prolific as what was going on in places like Philadelphia and New York, it just hasn’t gotten the same attention,” Britany Salsbury, curator of prints and drawings at the Cleveland Museum of Art and exhibition co-curator, told Forbes.com. “It felt important to draw attention to it and reintegrate (Karamu House) into what we know about Black artists working during the WPA years and in the years after the Harlem Renaissance.”

The Works Progress Administration was a New Deal program launched by the federal government during the Great Depression. Its aims were pouring millions of federal dollars into building projects supporting the public good like libraries, schools, hospitals, roads, and post offices. Hundreds of thousands were employed in the process, keeping millions of Americans off the streets and out of poverty.

The program also supported tens of thousands of artists–painters, printmakers, dancers, musicians, actors–through the Federal Art Project. Among them were photographer Dorothea Lange, sculptor Louise Nevelson, and painters like Jacob Lawrence, Willem de Kooning, Stuart Davis, Jackson Pollock, Philip Guston, and Marsden Hartley.

Imagine that, the federal government valuing and helping artists and the arts instead of working to destroy them.

The Harlem Renaissance was a cultural explosion of African American creativity across all disciplines during the 1920s. Key figures included Zora Neale Hurston, Augusta Savage, Aaron Douglass, James Van Der Zee, Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong, and Ella Fitzgerald.

“This is one of those instances in which there’s a dearth of scholarly attention paid to the mechanisms of artistic manufacture and production that were going on here because it’s Cleveland, precisely because it’s not New York, Chicago, or LA,” Erin Benay, associate professor of art history at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland and exhibition cocurator, told Forbes.com. “That was one of the things we wanted to rectify on both a scholarly level, but also on a much larger level for viewers and residents and people who share in this history and these centers.”

Karamu artists come up as an aside within scholarship on the WPA’s arts programs and the aftereffects of the Harlem Renaissance, but haven’t fully been integrated within the understanding of those topics scholarly or popularly.

Cleveland artists had direct connections to the Harlem Renaissance and wider American art world through personal networks, travel, and education. They aligned themselves with the philosophical architect of the Harlem Renaissance, Alain Locke. Their work was promoted by pioneering African American art historian James A. Porter.

Truth was, the Harlem Renaissance took place outside of Harlem. As Denise Murrell’s exceptional Metropolitan Museum of Art exhibition “The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism” detailed, what’s come to be known as the Harlem Renaissance was a flourishing of African American creativity and cultural production spanning the U.S. and the Atlantic Ocean.

“It’s a common misconception that the Harlem Renaissance was about Harlem,” Benay said. “We wanted to make sure that we weren’t just treating these artists biographically, both in terms of the biography of Cleveland and the biography of the specific artists, but rather that we were situating them within the proper art historical dues they’re owed, which is to think about them in this broader Harlem Renaissance trajectory from a stylistic perspective. Then also to integrate careful and precise research that shows the way that these artists were specifically connected to the WPA. There’s a vagueness around the artists and the relationship of Karamu House to the WPA that we really wanted to nail down with archival research.”

To that end, the exhibition is accompanied by a deeply researched catalog including a catalogue raisonné, an exhaustive, detailed compilation of all known prints produced by the group during the 1930s and 40s. Some had been previously unpublished. Extensive catalogue footnotes provide a roadmap for future art historians and scholars to find sources enabling them to think about these artists as individuals. The project is a launching pad for further scholarship and recognition.

Printmaking And Cleveland

‘My Son! My Son!,’ 1941. William E. Smith (American, 1913–1997). Linocut; image: 19.7 x 13.7 cm; sheet: 28.5 x 22.7 cm. The Cleveland Museum of Art, Gift of the Print Club of Cleveland, 1941.122.

© William E. Smith

Prints and printmaking have always been the artwork of the people. For the people. Democratic. Collaborative. Graphic. Relatable to and understandable by general audiences. Prints are more affordable to make and collect. Easier to transport and distribute. They’re lightweight, non-precious, and produced in multiples.

Printmaking has served as a means of taking a message to the masses since its invention and Martin Luther through the Mexican revolution and today. It’s always been a tool of protest. Woody Guthrie put a sticker on his guitar reading, “this machine kills fascists;” the same can be said of the printing press. The medium has always been a tool for underrepresented people.

It was perfect for the artists working at Karamu House during the Great Depression and Jim Crow segregation in America.

“Printmaking is a collaborative medium,” Benay explained. “It’s hard to successfully make prints alone. Someone has to have clean hands to handle the papers. Someone usually helps with the inking. There’s a lot of trial and error. This idea of collaboration and community was integral to Karamu House and transcended any particular aspect of the arts programming.”

Cleveland also had a strong history of commercial lithography and was one of five cities in the United States designated as a site for a graphics workshop as part of the Works Progress Administration. Karamu House, however, was not a WPA community art center like the South Side Community Art Center in Chicago or the Harlem Community Art Center. The WPA graphics workshop did provide Karamu artists with access to a wide range of materials, tools, and expertise.

Subscription services for the purchase of prints unrelated to Karamu House were also flourishing in Cleveland during the 40s–nationally as well–all adding to the uniquely fertile ground under which the Karamu House Inc. printmaking project began.

“One of the ways this (exhibition) speaks to a larger art historical story than just a Cleveland story is in the way that it focuses on printmaking, and on prints in particular, which is also a marginalized medium in art histories and doesn’t get the attention it deserves,” Benay said. “The story of printmaking ties directly to the story of Black artists and to the success of Black artists nationally, and the ways that then fueled trajectories for art making in the 1960s and 70s, not just for Black artists, but for all artists of color, particularly in the United States.”

Black artists like Charles White and Elizabeth Catlett. Chicano artists. All prominently used printmaking in the mid and later 20th century to great prominence and effect.

Karamu House Inc.’s greatest recognition within the broader American art world occurred in 1942 with an exhibition at Associated American Artists Gallery in New York, one of the major venues for seeing prints at the time on Fifth Avenue.

“Many of the Karamu artists were among the first Black artists collected by museums and white collectors, who helped to cultivate and create a Black art market, both in Cleveland, but also nationally,” Benay said.

Evolution Of Karamu House

Shortly after the 1942 exhibition and the end of World War II, Karamu House Inc. disbanded as a group. WPA funding ceased. Many of the artist’s careers were ascending and they explored individual opportunities elsewhere.

Artmaking at Karamu House kept on rolling however.

“Printmaking did not cease at Karamu House, in fact, the art program continued to foster and develop artists throughout the 60s and 70s, even when they didn’t always make their art on site,” Benay explained. “As art institutions like the Cleveland Institute of Art accepted more and more black students, sure, artists would seek professional development from an art school that had more robust offerings, but Karamu House continued to anchor the arts community by fostering exhibitions, by having print sales, and that was a huge part of the way that it cultivated professional development for Black artists in Cleveland and continues to do so to this day.”

Galleries at Karamu House remain fundamental sites of exhibition for Black artists in Cleveland. That began in the 50s.

An evolution.

As much as Benay and Salsbury want to situate Karamu House within broader national artistic currents surrounding the WPA and Harlem Renaissance, they are also taking care to point out what made it special. Its post-War evolution distinguished it from any arts center before or since.

“One of the primary ways Karamu House was distinct was that it became a stopping place for Black professionals traveling across the country in a very Green Book style trajectory,” Benay said.

“The Negro Motorist’s Green Book” was a travel guide published from 1937 through 1964 aimed at safely guiding African Americans to friendly lodging and dining establishments during Jim Crow segregation.

“It was not officially published as a Green Book destination, but it operated as one essentially, and because of its theater, because of its performing arts tradition, it had this gathering place quality, which is uncanny, because Karamu in Swahili means ‘a place of joyful gathering,’” Benay continued. “That only continued to be a part of its identity as it transitioned out of the 40s and into the Civil Rights era which is when Muhammad Ali and Amiri Baraka and MLK and Malcolm X and everyone is stopping at Karamu House. They came to Cleveland, but they specifically came to Karamu House, and its identity as an art center changed profoundly over the years to be a place that cultivated civil rights activism and social justice initiatives while carefully threading this needle not to be too provocative, so that it could still be interracial, that it could still welcome diverse audiences.”

Karamu House was unique from inception. About more than art from inception.

“It had things like a daycare, it truly was this third space for members of the Black community in Cleveland, but also as this racially integrated space at a time in Cleveland’s history, in America’s history, when there wasn’t a lot of interest in racial integration,” Salsbury said.

“Karamu Artists Inc.: Printmaking, Race, and Community” is free to visit and can be seen through August 17, 2025.

More From Forbes