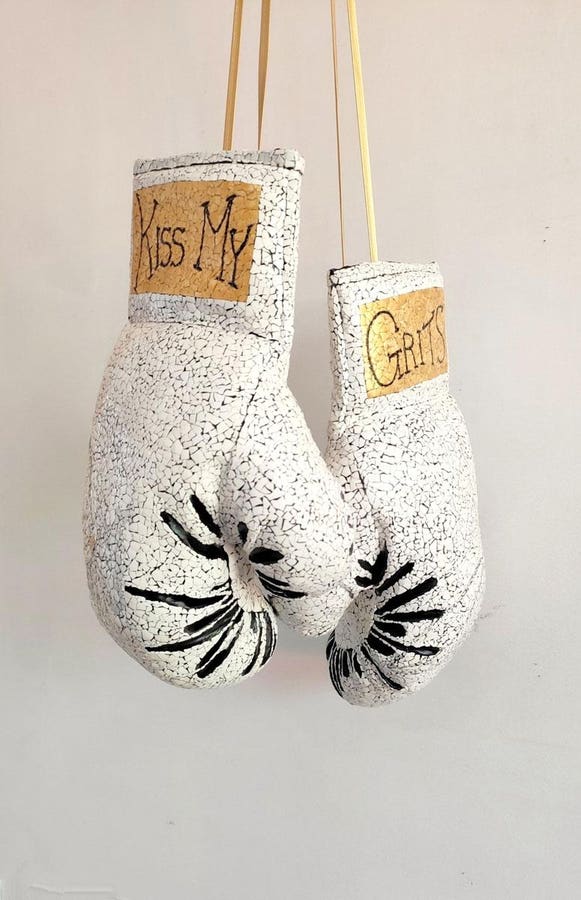

MyLoan Dinh, Kiss My Grits, 2024. Boxing gloves, eggshells, acrylic 18 x 13 x 5 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

Ogden Museum of Southern Art

On April 30, 1975, Saigon fell. For America, its disgraceful 20-year intervention in Vietnam had come to a disgraceful end. Finally.

For the citizens of South Vietnam who had been resisting the oncoming Communists and aiding the Americans, their war was not over.

In the hours leading up to the Fall, residents fearing political persecution swarmed the U.S. embassy hoping for a ride out. Thousands came. Panic. Chaos. Pictures of American helicopters on rooftops boarding long lines of South Vietnamese people led every newscast and newspaper front page worldwide. People pushing empty helicopters off Navy ship decks to allow for more helicopters carrying people to land.

For everyone who made it out of Saigon on American helicopters in those final hours, more couldn’t be rescued. Hundreds of thousands more from across South Vietnam couldn’t make it to the capital city. One and a half million people risked their lives crossing borders into the neighboring countries of Laos and Thailand.

Others embarked on treacherous boat voyages in the pursuit of sanctuary. They would come to be known as the Boat People. Between 1975 to 1992, nearly 2,000,000 Vietnamese risked their lives fleeing oppression after the Vietnam War. It remains one of the largest mass exoduses in modern history.

A large portion of the Vietnamese diaspora sought refuge throughout the United States, initially relocating to any region offering sponsorship. The Catholic Church was instrumental in these sponsorships. Then, as now, millions of Vietnamese people are Catholic.

Many of these refugees permanently settled throughout the American South, including enclaves in Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Florida, Georgia, Oklahoma, Virginia, North Carolina and the District of Columbia. The Gulf Coast was a particularly favored destination due to the similar subtropical climate and access to familiar shrimping and fishing industries. Mississippi River Delta culture in Louisiana and the Mekong River Delta culture in Vietnam share similarities. These are water-based lives.

The Ogden Museum of Southern Art in New Orleans commemorates the 50th anniversary of the Fall of Saigon with “Hoa Tay (Flower Hands),” an exhibition centering emerging and established Vietnamese American artists working throughout the American South. “Hoa Tay” showcases 12 artists who use diverse media and styles to forge their own distinctive vision, conveying narratives of the Vietnamese Diaspora, both personal and universal.

In Vietnam, a child is praised if they have many whorls on their fingertips. The more circles a Vietnamese child has on their fingertip, the more artistically gifted they are believed to be. Hoa tay, loosely translated to “flower hands,” are considered the marks of ingenuity, spirit and talent in the arts.

“You enter the South and you feel the Vietnamese influence–in cuisine and art, the nail industry is really popping down here, there’s a lot of Viet-Cajun restaurants,” exhibition collaborating curator Uyên Đinh told Forbes.com.

Đinh was born in Vietnam, immigrated with her parents to the U.S. when she was 14, and lived on the East Coast before heading to New Orleans in 2022 for a job at the Ogden after graduating from Barnard College in New York with an art history degree.

“When my dad found out I was moving to New Orleans, he was like, ‘you know, most of the people in our hometown immigrated there,’” Đinh recalls. “This is the largest Vietnamese community I’ve seen outside of Vietnam. It’s great. It definitely felt like a homecoming when I was moving here.”

Mardis Gras even has a Vietnamese krewe.

“The Vietnamese people are here, they’re making their voice known,” Đinh said. “As someone who is from Vietnam, is a Southern transplant, I see how (Vietnamese culture) is weaved into (Southern) culture in such a specific way that I didn’t see on the East Coast. A more vibrant, colorful way.”

The exhibition focuses on the Vietnamese American experience in the American South, not the experience of Vietnamese people living in the South with American intervention in Vietnam.

“These people are from the South; these are southern folks who have a very deep and very personal relationship to these two lands,” Đinh said.

Vietnamese Nail Salons

Christian Đinh, ‘In the mud, what is more beautiful than a lotus?,’ 2022. Porcelain and silk 16 x 16 x 6 inches. Gift of the artist 2023.3.1

Ogden Museum of Southern Art

“Hoa Tay (Flower Hands)” artists include second and third generation Vietnamese Americans, as well as refugees and Boat People. The exhibition goes out of its way to reinforce that there is no singular Vietnamese experience in America any more than there is a singular experience in America for any other ethnicity of people.

“Because of their different starting points, all of these artists have interesting perspectives on what it means to be Vietnamese nowadays on a global stage,” Đinh said. “This is not a monolithic community. People are allowed to hold different point of views about the (Vietnam) War, about their Vietnamese identity, about their heritage, and people are allowed to do that because they themselves come from different backgrounds.”

For all the diversity, an unmissable theme runs through the presentation: the importance of nail salons.

Visitors will recognize this in Christian Đinh’s “Nail Salon” series hands. Each set of hands within the series are porcelain casts of display hands routinely found in nail salons. The series illustrates the ways in which the Vietnamese nail salon industry in the United States embodies the success of the Vietnamese American community.

Exhibition artist Kimberly Ha’s mother’s nail salon was the formative backdrop of her childhood and became a significant source of material for her artwork. Vietnamese women like Ha’s mother transformed the nail salon industry. Incredibly, this path was partly inspired by actress and activist Tippi Hedren. Visiting a Vietnamese refugee camp in California in 1975, upon meeting the women there, Hedren introduced them to Hollywood-style nail care.

“In the 70s, that’s what happened; that’s how these Vietnamese refugee women were formally introduced to this industry,” Đinh said. “It’s something that is so personal to our artists. The majority of the artists in our show have spoken of having family members who work at the nail salon. A lot of these subjects are about nail salons, growing up around the nail salon, watching their parents and family work at the nail salon.”

Vietnamese women had a nail salon culture from back home and took those skills to find work in America’s existing salons, supporting their families.

“(Nail salons were) already a big industry in Vietnam. My aunt was a nail salon artist in Vietnam,” Đinh explained. “Tippy was this lady who spearheaded this program and was a conduit that helped formalize the industry, but the skills were there. She was trying to see how to translate the skills into a profitable industry for these women.”

Introduced to the industry, more and more Vietnamese women eventually opened their own salons, employing more and more Vietnamese women. Today, the industry generates over $8 billion in revenues.

In her “Full Set” series, Ha combines intimate memories with 21st century nail design, visually evident on each carefully curated set of nails–leading craft into the realm of fine art through artistry and aesthetic vision.

50th Anniversary Fall Of Saigon Remembrances Across America

A CIA employee (probably O.B. Harnage) helps Vietnamese evacuees onto an Air America helicopter from the top of 22 Gia Long Street, a half mile from the U.S. Embassy.

Bettmann Archive

Fiftieth anniversary events commemorating the Fall of Saigon (now alternately called Ho Chi Minh City) can be found across the United States. In New Orleans, The Historic New Orleans Collection focuses on Vietnamese elders, the original refugees, and how they built a life in the city.

Other exhibitions, events and commemorations can be found across the country including in Boston, Orange County, CA, San Jose, CA, Seattle, at the Lincoln Memorial Reflecting Pool on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., and at the USS Midway Museum in San Diego. The Midway was one of the ships refugee laden helicopters fleeing Saigon landed on.

American diplomats, however, will not be acknowledging the anniversary. Reporting by The New York Times found that the Trump Administration, continuing to pursue its Yankee Doodle Dummy, jingoistic, America-can-do-no-wrong, alternate reality version of American history, has instructed diplomats not to participate in events related to the Fall of Saigon. This shameful chapter in the long and shameful history of failed U.S. interventions overseas conflicts with the Administration and its acolytes’ futile attempts to find the elusive “great” period of the nation’s past it seeks a return to.

More From Forbes