The responsibility of handling all official communication during the period of the Maratha Empire was assigned to the Chitres of Kolhapur in Maharashtra. It was none other than Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj, the iconic Maratha king, who had appointed this family for such an important role sometime in the mid-1600s.

Several centuries down the line, Professor Eknath Vasant Chitnis – a descendent of the Chitres – kept alive the family legacy of being involved in the field of communication and played a pioneering role in India’s space programme. EV Chitnis, as he was later known, went on to become one of the key titans who laid the early foundation of the Indian Space Research Organisation (Isro).

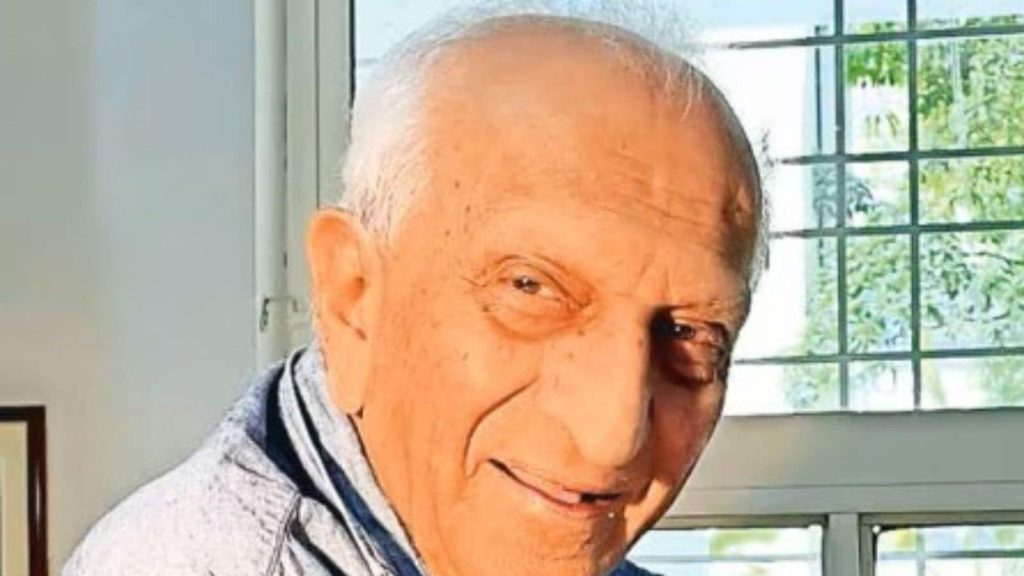

Chitnis turns 100 on July 25.

“My family has a long history dating back to Shivaji Maharaj’s times in the 1630s… Our family got its name Chitnis from Shivaji Maharaj, but the family name was originally Chitre. My ancestors were appointed as Shivaji’s Chitnis (a title responsible for handling all official communication and correspondence). The Chitres remained associated throughout the Maratha empire’s reign,” Chitnis said.

Born in Kolhapur in pre-Independent India, Chitnis did his schooling and higher education in Poona (now Pune), spending his formative years living in the peth areas (old Pune city) and in Pune Camp locality. Both these worlds gave Chitnis the right mix of traditional and cosmopolitan upbringing and outlook. His father was a medical doctor and would often have to treat patients from other nationalities, including the Englishmen who resided in the region back then.

“My father was fond of horse racing and horses. He often took me along to the Poona race course,” Chitnis said, pulling out a fond memory in this connection. Once, an Arab patient had consulted his father and was cured from his prolonged illness.

“In return, the Arab patient visited our home in Pune camp and offered my father a white pony as a gift. I was too elated with the thought of finally getting a horse at home, but my dream shattered in no time. After thanking the patient for the gift, my father politely declined the offer. He remarked that accepting it would be like having a ‘white elephant’ at home!” recalled Chitnis.

Childhood lessons

He added that his childhood years growing up in the peth areas and Pune Camp during the 1930s allowed him to grow and learn important lessons on communication, society, food and culture early on through his interactions with friends from the Parsi, Muslim, Christian, and Hindu communities, besides the Arabs and the British.

Story continues below this ad

After horses, young Chitnis enjoyed cricket and would not miss tuning in to the radio commentary during every match. “I learned to speak English, especially the numbers, even before formally learning the language in school… All thanks to the cricket commentary relayed on the radio,” he said.

At the peak of India’s freedom movement, Chitnis and his friends would attend study classes organised by all political parties after college hours. The Isro veteran said, “We were all living in tumultuous times, and India’s freedom uprising was gaining momentum. As college students, we would attend study classes during evenings. This helped us to stay updated about what Mahatma Gandhi, Pandit Nehru and other freedom fighters were doing to oust the British Raj.”

An alumnus of Sir Parashurambhau College, Wadia College and the prestigious Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), USA, Chitnis married Kumud Samarth. She was a cancer researcher who was training in the US before their wedding and continued to pursue her research post-marriage and during their stay in Ahmedabad.

“My friends would tease me that I am marrying a foreign-returned lady!” he said, laughing. Kumud Chitnis passed away in June 2020.

Story continues below this ad

Association with Vikram Sarabhai

Chitnis was Vikram Sarabhai’s right-hand man. To date, he has fond memories of his first interaction with Sarabhai, the father of India’s space programme, sometime in October 1952. It was during Chitnis’ job interview for a post at the Textile Research Association in Ahmedabad that the two met.

“I wanted to work as a researcher at the Physical Research Laboratory (PRL) and to do so, I needed the job. During the final round of the interview, for which Sarabhai was also present, I asked him up front whether he was Vikram Sarabhai. To which, he responded, ‘I am Vikram’.”

Chitnis worked as a lecturer at a college in Gujarat’s Anand till Sarabhai managed to get him funded through a scholarship. Chitnis finally joined Sarabhai’s team on March 16, 1953. Their association grew stronger as India’s space programme took shape. Team Sarabhai established the Indian National Committee for Space Research (INCOSPAR) in 1962 and later ISRO in 1969.

MIT comes knocking

Sarabhai kept Chitnis busy at Kodaikanal over the next two years on a cosmic ray project carried out in collaboration with MIT. Impressed with his work, MIT offered Chitnis a researcher’s job but he flatly declined the offer. Surprised, MIT wrote to Sarabhai, who then insisted that the young Chitnis take up the bright opportunity.

Story continues below this ad

“There was a lot of data which was analysed at MIT, and remarkable work was later published. It took three months for the news of the Indo-China war of 1962 to trickle down to a large Indian population. That was when Sarabhai decided to initiate the space programme in India, with a vision for laying the country’s satellite communication and using it effectively to improve education, meteorology, environment and agriculture,” Chitnis told.

In July 1961, Sarabhai recalled Chitnis from the US and gave him the responsibility of planning India’s space programme and coming up with a definite roadmap. This, while Sarabhai was simultaneously working with the government on this idea.

India had no prior experience of making rockets or propellants till then. Sarabhai first tasked Chitnis with the location hunt for a suitable rocket-launching site. And Chitnis was aware that his role and inputs were crucial. “I visited Cape Canaveral in the US. It gave me an idea of what a space port should look like,” he said.

Cape Canaveral, home to the Kennedy Space Center and the Cape Canaveral Space Force Station, is a key rocket launching site in the US.

Story continues below this ad

Scouting for a launch site

Back in India, Chitnis and a handful of young colleagues made multiple trips to Kerala, scouting for a rocket launch site. They took several chopper rides between the Ashtamudi kayal (backwaters) in Quilon (present day Kollam district) and Thiruvananthapuram – looking for an ideal land to set up rocket launch pads for performing sounding rocket experiments. He shared an interesting story of one of his visits to the Kerala coastal site.

“Since there was no official car owned by PRL till then, I decided to first take a bus from the quarters, then an autorickshaw and reach Ahmedabad airport. A little before I set out, Sarabhai rang me up enquiring about the journey. Upon learning my plans to get to the airport, he asked to stay back, and he personally drove me to the airport. Seeing me with Sarabhai, many at the airport were surprised. Thereafter, every flight I took out of Ahmedabad airport, I would be given celebrity-like treatment by the airport staff,” remembered Chitnis.

It was in November 1962 that Thumba, a small fishing island near Thiruvananthapuram, was finally chosen for the establishment of India’s Equatorial Rocket Launching Station. Thumba was an ideal location, closer to the magnetic equator, thus permitting the budding space scientists to take up early experiments with the atmosphere and ionosphere.

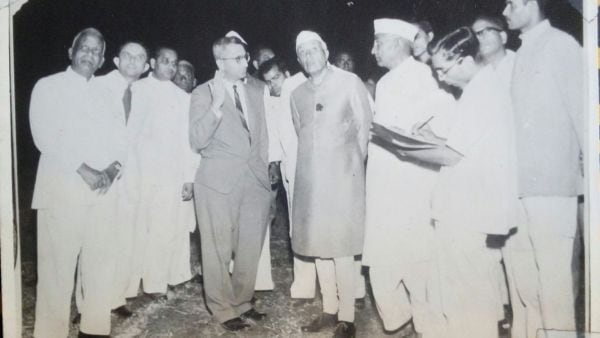

Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru during an interaction with ISRO scientists in 1962. Vikram Sarabhai (2L) and Eknath Chitnis (4L, next to Nehru in suit) seen explaining the working of satellites (Image Credit – The Indian Express archive)

Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru during an interaction with ISRO scientists in 1962. Vikram Sarabhai (2L) and Eknath Chitnis (4L, next to Nehru in suit) seen explaining the working of satellites (Image Credit – The Indian Express archive)

“We were mostly in Quilon and Thiruvananthapuram. Kerala is a beautiful and green state,” he said, adding that the then governor of Kerala, V V Giri, had generously hosted the Isro team during some of their visits.

Story continues below this ad

When Sarabhai wished to expand the rocket launches and space programme, Chitnis and company were once again roped in and sent to study India’s east coast for setting up a full-fledged space port.

In the 1970s, India’s space journey took off from Sriharikota.

Cut to February 2025, when Isro yet again tasted success following its 100th launch and Chitnis said, “I remember first going to Sriharikota… Almost a barren land, a big island off the Andhra Pradesh coast. But it was good for rocket launches.”

Finding A P J Abdul Kalam

India may not have known its Missile Man Dr A P J Abdul Kalam, the former scientist with Isro and the Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO), if it were not for Chitnis. He said, “I, along with Sarabhai, and two others, were on the interview panel to select candidates for a training programme organised by NASA (National Aeronautics and Space Administration). Sarabhai asked me to review Kalam’s application, and impressed by his qualifications, I recommended him for the programme.”

Story continues below this ad

Many decades later, when Kalam was serving as the 11th President of India, Chitnis and his family paid him a visit at the Rashtrapati Bhavan. “I always remember Prof E V Chitnis as a father figure in Physical Research Laboratory, integrating scientists and technologists and as one of the pioneers of the SITE (Satellite Instructional Television Experiment ) programme…,” Dr Kalam had spoken in his address at the World Space Vision 2050 and India, a programme organised to dedicate the Insat-4B satellite to the nation at Hassan, Karnataka, in June 2007.

Chitnis was awarded the Padma Bhushan in 1985. Four decades later, his son, Dr Chetan Chitnis, was awarded the Padma Shri in 2025. The junior Chitnis studies malaria parasites and is currently at the Institut Pasteur, France.

Settling down in Pune

Post-superannuation as the director of the Space Application Centre (SAC), Ahmedabad, Chitnis moved to Pune, where he continues to reside. “We left Ahmedabad in 1988 and thought of spending some time at Pune University. For almost 20 years, I taught there…and I had great fun teaching,” he said.

He remained associated with the University of Pune, engaging in lectures on communications and related topics. The last batch he engaged was part of a course on Development Communication at the Department of Communication Studies (now renamed as Department of Media and Communication Studies) during 2012 – 2013.

Story continues below this ad

Speaking about his life, Chitnis said recently, “I eat and sleep well and am enjoying life. I eat normal, home-cooked food but never a heavy meal. I enjoy fish and chicken. Now I am completely relaxed… Unless one is relaxed, one does not live long.”

A lover of Indian classical music and an avid reader, Chitnis would, until recent years, spend the late-night hours catching up on the latest developments through books as well as English and Marathi newspapers. But of late, he has been doing limited reading. “I do read but prefer short pieces on history… see, I’m linked to Maratha history,” he said.