Credit: MIT

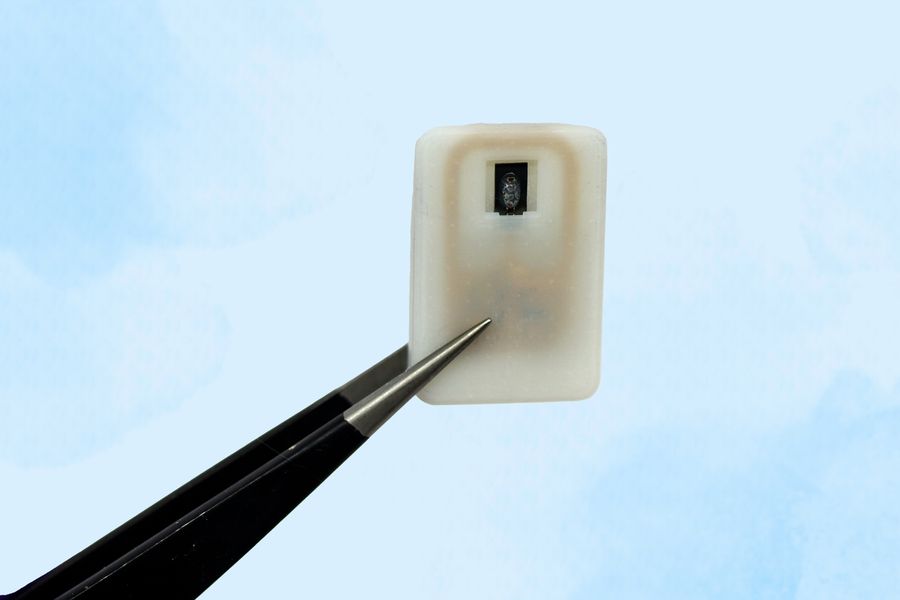

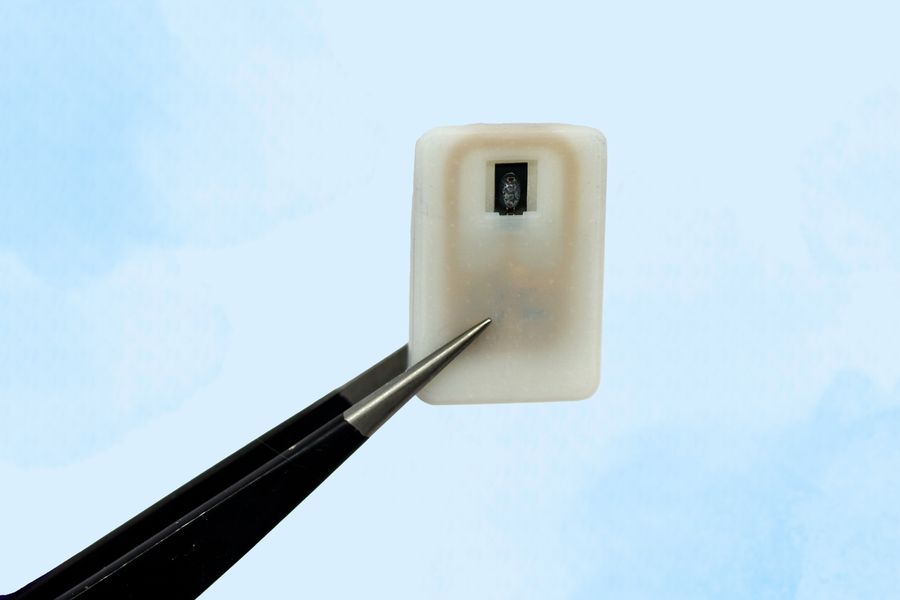

The device is about the size of a quarter and can carry either one or four doses of a powdered glucagon in a small reservoir.

Researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) have developed an implant that one day could help patients with Type 1 diabetes experiencing hypoglycemia, a serious complication where glucose levels become too low.

In people with Type 1 diabetes, the pancreas does not make insulin. But these patients also lack glucagon, a hormone that stimulates the liver to release glucose into the bloodstream. Without glucagon, patients can experience dangerously low blood sugar levels, a condition that causes around 10% of all deaths in patients with Type 1 diabetes.

Researchers at MIT have shown that an implant that contains a reservoir of glucagon could be used to deliver an emergency dose without injections. The implant can be stored under the skin, and the glucagon can be deployed in times of low glucose. MIT’s research of the device used in mice was recently published in Nature Biomedical Engineering.

“Our goal was to build a device that is always ready to protect patients from low blood sugar. We think this can also help relieve the fear of hypoglycemia that many patients, and their parents, suffer from,” Daniel Anderson, Ph.D., one of the study’s authors and a professor in MIT’s Department of Chemical Engineering, a member of MIT’s Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research and Institute for Medical Engineering and Science (IMES), said in a news release.

Type 1 diabetes is an autoimmune disease where the immune system destroys insulin-producing beta cells in pancreatic islets. Insulin helps the body use glucose for energy, and glucagon is released when glucose levels become too low. About 2 million Americans have Type 1 diabetes. About 4% of patients using insulin experience hypoglycemia in Type 1 diabetes, but patients generally only seek treatment when symptoms are severe.

Some patients carry preloaded syringes of glucagon, but it isn’t always easy for people, especially children, to know when they are becoming hypoglycemic.

“Some are unaware that they’re hypoglycemic, and they can just slip into confusion and coma. This is also a problem when patients sleep, as they are reliant on glucose sensor alarms to wake them when sugar drops dangerously low,” Anderson said.

The device designed by MIT is about the size of a quarter and contains a small drug reservoir made of a 3D-printed polymer. The reservoir is sealed with a special material known as a shape-memory alloy, which can be programmed to change its shape when heated. Researchers created a powdered version of glucagon that can remain stable for much longer.

Each device can carry either one or four doses of glucagon, and it also includes an antenna tuned to respond to a specific frequency. That allows it to be remotely triggered to turn on a small electrical current, which is used to heat the shape-memory alloy. When the temperature reaches the 40-degree threshold, the slab bends into a U shape, releasing the contents of the reservoir.

In mice, researchers found that blood sugar levels began to level off within less than 10 minutes of activating the drug release. They found that scar tissue around the implant did not interfere with the release of glucagon.

The researchers also tested the device with a powdered version of epinephrine. They found that within 10 minutes of drug release, epinephrine levels in the bloodstream became elevated and heart rate increased.

In this study, the researchers kept the devices implanted for up to four weeks, but they now plan to see if they can extend that time up to at least a year. MIT researchers are continuing with studies in animals but hope to begin human trials within the next three years.

The research was funded by the Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust, the National Institutes of Health, a JDRF postdoctoral fellowship, and the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering.