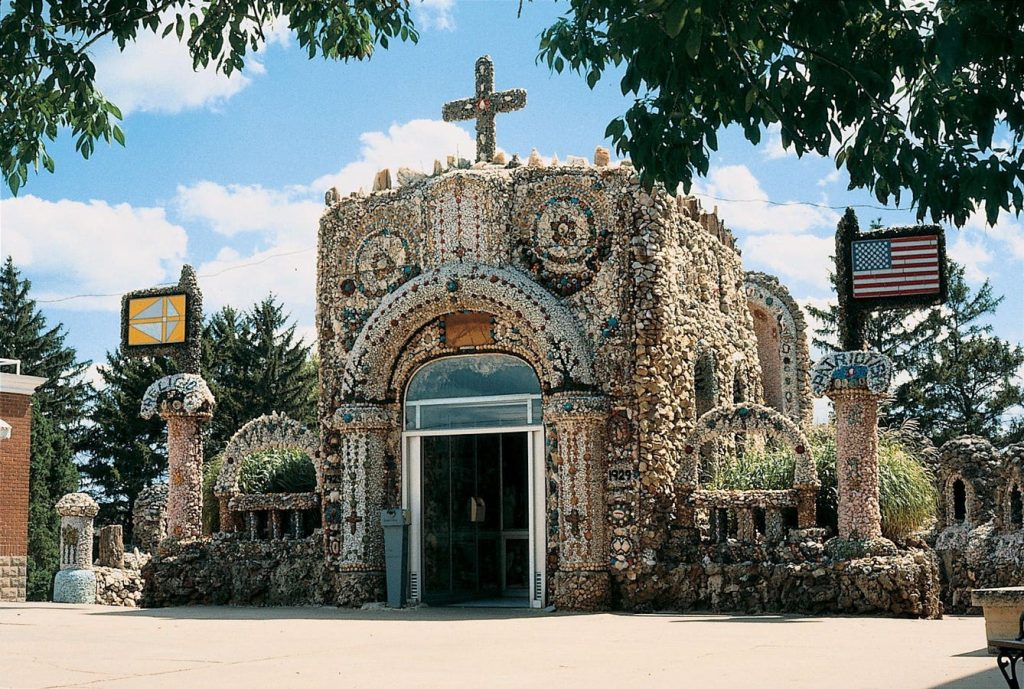

Father Mathias H. Wernerus, Holy Ghost Park (the Dickeyville Grotto, site view, c. 1995), Dickeyville, WI, c. 1920–1931.

John Michael Kohler Arts Center Artist Archives

In the days before Christianity spread across Europe, pagan rituals took place in caves often containing springs. The wonder and awe of nature and water was worshiped.

When the Christians took over, they converted these grottos into shrines for their own worship. Particularly Catholics.

German Catholic immigrants to America in the first half of the 20th century, tens of thousands of whom found their way to the Midwest, brought this sacred grotto tradition from the old country. With a twist. Their new grottos were decidedly more homespun, constructed of concrete–a new material at the time–and embellished with all manner of everyday items from seashells and glass bottle fragments to doorknobs and broken China.

One of the most famous such sites is the Dickeyville Grotto in tiny Dickeyville, WI in the state’s extreme southwestern corner. The Dickeyville Grotto was built between 1924 and 1930 by Father Mathias Wernerus who integrated organic minerals, found objects, and hundreds of gearshift knobs donated by Henry Ford into the shrine.

Another of the region’s most prominent grottoes is Father Paul Dobberstein’s Grotto of the Redemption constructed between 1912 and 1954 in equally tiny West Bend, IA in that state’s north-central region. It is estimated he traveled over 60,000 miles to collect geological specimens, eventually incorporating them into his assemblage occupying an entire city block.

Dauberstein and Wernerus both went to seminary in Milwaukee.

Both sites became nationally known tourist attractions almost immediately after their dedication, and visitors from throughout the Upper Midwest were inspired to try their hand at embellished concrete sculptures themselves. One such soul was Madeline Buol (1902–1986), a devout Catholic and beauty shop owner living in Dubuque, IA, right across the Mississippi River from Dickeyville. Buol visited both the Dickeyville Grotto and the Grotto of the Redemption.

She did more than visit.

Inspired, Buol began gathering grotto materials in early 1943 and began building her own grotto in 1946. She wrote directly to Wernerus and Dobberstein for construction advice. Over the following 30 years, she traveled the country collecting more supplies and inspiration for her grotto.

A grotto, unlike those in Dickeyville and West Bend, that went mostly unregarded.

Until now.

Opening June 7, 2025, and on display through May 10, 2026, Buol’s rescued and conserved grotto takes center stage during “A Beautiful Experience: The Midwest Grotto Tradition,” an exhibition at the John Michael Kohler Arts Center in Sheboygan, WI exploring the regional vernacular tradition of grottoes—outdoor sculptural environments created as religious shrines imbued with elements of culture, religion, geology, and patriotism, often made by immigrants.

The exhibition is the first public showing of Buol’s monumental 13-piece grotto since it was saved from destruction out of the artist’s yard in 2011 by the Kohler Foundation and gifted to the John Michael Kohler Arts Center.

“Grottoes are artist-built environments—a core focus of JMKAC—and they are places where creativity is inseparable from lived experience,” Amy Horst, executive director of the John Michael Kohler Arts Center, said. “Often created outside of traditional art contexts, these extraordinary sites are frequently unrecognized and left unpreserved. These awe-inspiring assemblages hold deep significance in the cultural history and present of the Midwest.”

Madeline Buol

Madeline Buol, Buol Grotto and Sculptures (site view, n.d.), Dubuque, IA, 1946–c. 1960.

Lisa Stone

Grotto architecture mainly comprises concrete embellished with objects including marbles, toys, figurines, fossils, and geodes; it reflects local industries, decorative trends, and geology, creating a documentation of the maker’s life, faith, and home. They have inspired pilgrimage, tourism, reflection, and community gathering for over a century across the Upper Midwest.

“When the German Catholics came (to America), it was very important to them that all of their services remain in German, but they also didn’t want to alienate their new neighbors and country,” Laura Bickford, collections curator at the John Michael Kohler Arts Center and exhibition co-curator, told Forbes.com. “The grottos became this way of saying, ‘We’re Catholic, just like you. We use all the same places of worship and traditions of the Stations of the Cross and the Sacred Heart shrine that you do. So, even though you feel excluded from our services, we all are practicing the same religion.’”

Not only the same religion of Catholicism, but the same religion of devout American patriotism.

Remember, as German Catholics were immigrating to America in the first half of 20th century, the United States was fighting two wars against their homeland. Americans were suspicious about the loyalties–both religious and nationalistic–of their new neighbors with their strange language and accents.

Many grotto builders, including Buol, went out of their way to incorporate American flags, eagles, and other blatant patriotic imagery into their structures in an effort to assure the community they were now red, white, and blue through and through.

“The idea of grottos came from Europe where they were originally in caves and off shoot places as (sites) for meditation and a kind of silent, personal, private relationship with God people could seek away from the city,” Bickford explains. “When (German Catholics) came (to the Midwest), not finding the natural elements they needed, they made them, and a lot of them start with a central, cave like structure.”

As Buol’s does.

Buol’s concrete grotto sculptures, ranging in size from two feet to over eight feet tall, are embellished with objects collected over decades including toys, colored glass, family keepsakes, shells of varying shapes and sizes, and figurines and stones gathered during her travels. Among the components she created are a star-shaped sculpture, two rosaries, and an interpretation of the Dickeyville Grotto.

The exhibition takes its title from a slogan found on brochures, maps, and souvenirs from the Dickeyville Grotto. In addition to Buol’s grotto, “A Beautiful Experience” includes objects related to the Midwestern grottoes that directly inspired her—the Dickeyville Grotto, Jacob Baker’s “dream houses,” the Rudolph Grotto, and the Wegner Grotto. Also featured are new works by contemporary artists Stephanie Shih and E. Saffronia Downing responding to the grotto tradition.

Buol is one of the only known female grotto builders. She constructed most of her sculptures by herself in the basement. While it can be assumed others existed, no other grottos produced by women are as large or as well-known as Buol’s today.

That recognition is owed, in large measure, to the Kohler Foundation and the JMKAC.

Art Environments

Paul and Matilda Wegner Grotto (site view, 2022), Cataract, WI, c. 1929–1942.

Monroe County Local History Room & Museum.

The Kohler Foundation is the philanthropic arm of the Kohler Co., a global manufacturing giant headquartered in Kohler, WI. You’ve probably interacted with a Kohler product today–if you’ve used the toilet or washed your hands, anyway. Kohler produces sinks and tubs and toilets and bathroom fixtures popular worldwide for the past 100-plus years.

The Kohler Foundation has always had an emphasis on supporting the arts, and since the 1970’s, the preservation of art environments, folk architecture, and collections by self-taught artists has been a major focus. Artworks exactly like Buol’s.

In 2011, 25 years after Buol’s death, the Kohler Foundation, which additionally supports the preservation of Wisconsin cultural heritage and art environments, including other major grotto sites, acquired Buol’s sculptures to save them following the sale of her house. The grotto underwent extensive conservation and was gifted to the John Michael Kohler Arts Center in Sheboygan, next door to Kohler, an hour’s drive north of Milwaukee, where it entered the Art Preserve collection.

Founded in 1967, the JMKAC is the only institution in the world collecting artist-built and artist home-based environments. It is a leading center for research and presentation of self-taught and folk artists, preserving and championing work found nowhere else.

In the summer of 2021, JMKAC expanded to include a second site, the jaw-dropping Art Preserve three miles away. The Art Preserve is the world’s first and only museum dedicated to the presentation, care, and study of art environments. Art environments are the typically fantastical creations of artists working outside of the mainstream who give over their entire homes and yards to their creative pursuits.

Environment builders go beyond the production of discreet, individual objects–like paintings or sculptures–to create entire worlds of imagination taking over their surroundings. Hundreds of sculptures. Thousands of paintings. All amidst and amongst their homes.

These spectacular environments and their all-consuming nature are often a form of therapy, a response to loneliness, boredom, trauma, mental illness, or religious mania–sometimes a combination.

The Upper Midwest, and Wisconsin in particular, land of taverns and fish fries and supper clubs, is also a hotspot for art environments.

The area is full of handymen and women; tinkerers with the ingenuity and knowhow to produce objects from concrete and wood and scrap metal, all of which can be found cheaply and in abundance across the state. Wisconsinites are also distinguished by their puritanical work ethic. Wisconsinites like to keep busy, keep busy with their hands. The environment builders have no chill and they need to constantly be doing something to stay alive–like a shark swimming.

The Art Preserve’s 56,000-square-foot, three-level building provides exhibition space and visible storage for more than 25,000 works in the Arts Center’s world-renowned collection, including complete and partial environments by more than 30 vernacular, self-taught, and academically trained artists.

The John Michael Kohler Arts Center holds the world’s largest collection of art environments, Because these artists create so much work, and because JMKAC collects in depth, trying to protect as much as possible from the few artists it collects instead of a little bit from a wide array of artists, the collection is relatively narrow compared with the number of artists found in a typical art museum’s permanent collection, but exceptionally deep–hundreds or thousands of items from each artist represented, not merely one or two objects.

To support “A Beautiful Experience,” JMKAC is working on a grottos road trip guide. The Dickeyville Grotto has recently been restored and is in as good a condition as it’s been in years. A guide to visiting art environments across Wisconsin already exists.

Both the Arts Center and the Art Preserve are free to the public.

More From Forbes