We don’t normally spend a lot of time writing about IBM mainframes, but these big iron systems drive a lot of transactions in the world – transactions flush with demographics and context that will feed into AI models – and will be doing native and integrated AI processing for the applications that push those applications. And most of the other big iron machines installed in the world are based on Big Blue’s other processing line, the Power Systems machines based on a dozen generations of Power RISC CPUs.

These System z and Power Systems lines are running mission critical applications, and they are not easily replaced. The trouble for IBM is that both machines have come to the end of their most recent product lines and sales are slowing, as they always do, ahead of expected new product launches in the second half of 2025.

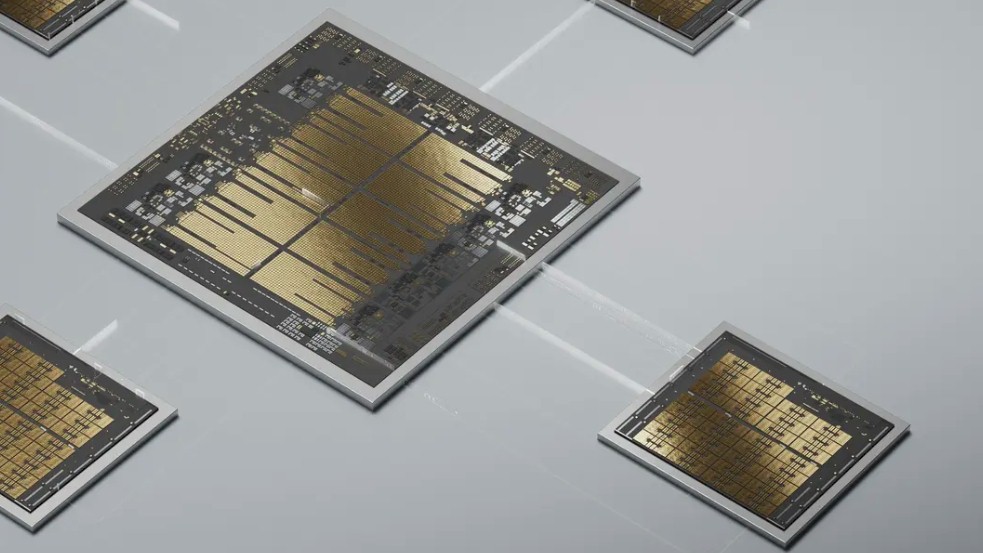

Big Blue is coiled to spring with the System z17 mainframes to start shipping in June with integrated AI processing on the “Telum II” z17 CPUs as well as on the “Spyre” external AI accelerators that are based on similar matrix math engines as are embedded in the z17 cores. And the Power11 processor is also coming later this year, with its own tweaks and tunings for running on-chip AI, supporting larger and faster memory subsystems (key for SAP HANA and Spark in-memory database workloads).

Until these two big iron machines start shipping, it will be a bit lean for Big Blue, and its software and consulting businesses will have to try to pick up the slack – and do so in an increasingly challenging macroeconomic environment. So far, it looks like this is happening as Red Hat Enterprise Linux and its adjuncts for virtualization and containerization take off. GenAi consulting and software sales are doing their parts, too.

In the first quarter, IBM’s revenues were up six-tenths of a point to $14.54 billion. Gross profit rose by 3.7 percent to $8.03 billion, but unlike in the year ago quarter when IBM had a $502 million tax benefit it had in its back pocket, in Q1 2025 IBM had higher research and development costs and had to pay $103 million in taxes, so net income was down by 34.3 percent to $1.06 billion.

IBM’s Infrastructure group, which sells storage and servers and resells networking from others, had $2.89 billion in sales, down 6.2 percent year on year. At this point in the product cycle most customers know they are going to wait for z17 or Power11 systems, but those that need capacity can do so by turning on latent capacity that is available on demand in most of the z and Power machines. And so, the revenues that IBM gets from such upgrades are done with a “golden screwdriver” and therefore have very little costs associated with them. And this, even as hardware revenue drop, hardware margins go up. Pre-tax income for the Infrastructure group rose by 13.3 percent to $248 million.

Withing this systems group, server and storage sales was down 10.2 percent to $1.63 billion, with another $1.26 billion in revenues for infrastructure support.

IBM’s Software group, which is heavily tied to its System z mainframes but which also gets revenues from the Power platform as well as alternative system architectures such as X86 and Arm, had $6.34 billion in sales in Q1 2025, up 7.4 percent year on year and delivering gross profits of $5.3 billion (83.6 percent of revenues), Pretax revenues for Software group were up by 23.1 percent to $1.85 billion. IBM’s Consulting group, which runs applications for customers, does technology consulting and business transformation engagements, had $5.07 billion in sales, down 2.3 percent year on year.

As you know, we try to figure out what the underlying systems business is doing in terms of revenues and pre-tax income every quarter. This includes systems, storage, operating systems, transaction processing and other base middleware but not databases and higher level software and applications, as well as tech support and financing for the systems that Big Blue sells.

As best as we can figure, IBM’s “real” systems business – meaning its legacy mainframe and Power platforms not counting Red Hat products – accounted for $5.92 billion in revenues, down 2.5 percent year on year, with pre-tax income of just a tad over $3 billion, which is 51 percent of sales.

The Red Hat business grew by 12 percent in the quarter to $1.86 billion, and around 70 percent of that was additive to the “real” systems business. So add them up you get a purplish “real” systems business that was off a fraction of a percent to $7.22 billion in Q1.

As we are fond of pointing out, IBM’s systems business was recovering when it bought Red Hat, but the addition of Red Hat and now HashiCorp will help accelerate that business even more.

We are also watching IBM’s GenAI book of business very carefully, too. Arvind Krishna, INM’s chief executive officer, said on a call with Wall Street analysts going over the Q1 numbers that IBM’s cumulative GenAI bookings were above $6 billion, and that about a fifth of that was for software and that four-fifths were for consulting. IBM does not really sell GPU accelerated machines, so it does not have any direct GenAI hardware revenues, but it will have them soon when System z17 and Power11 machines with Spyre accelerators come to market.

IBM has not said how much GenAI revenues it has booked as yet, and it is very hard to guess what it might be. We are sure that Big Blue wishes the pipeline of GenAI deals was bigger, the bookings were bigger still, and the revenues were bigger. But for now, it is enough to offset higher costs and lower margins elsewhere, and as the z17 and Power11 systems and Spyre accelerators come to market running the models in the Watson.x AI stack, the company has somewhere around 80,000 fairly current and motivated customers who will need new machinery to run AI algorithms inside of or adjacent to their applications. This could double IBM’s Infrastructure group revenues, depending on what it charges for Spyre accelerators and Watson.x models.