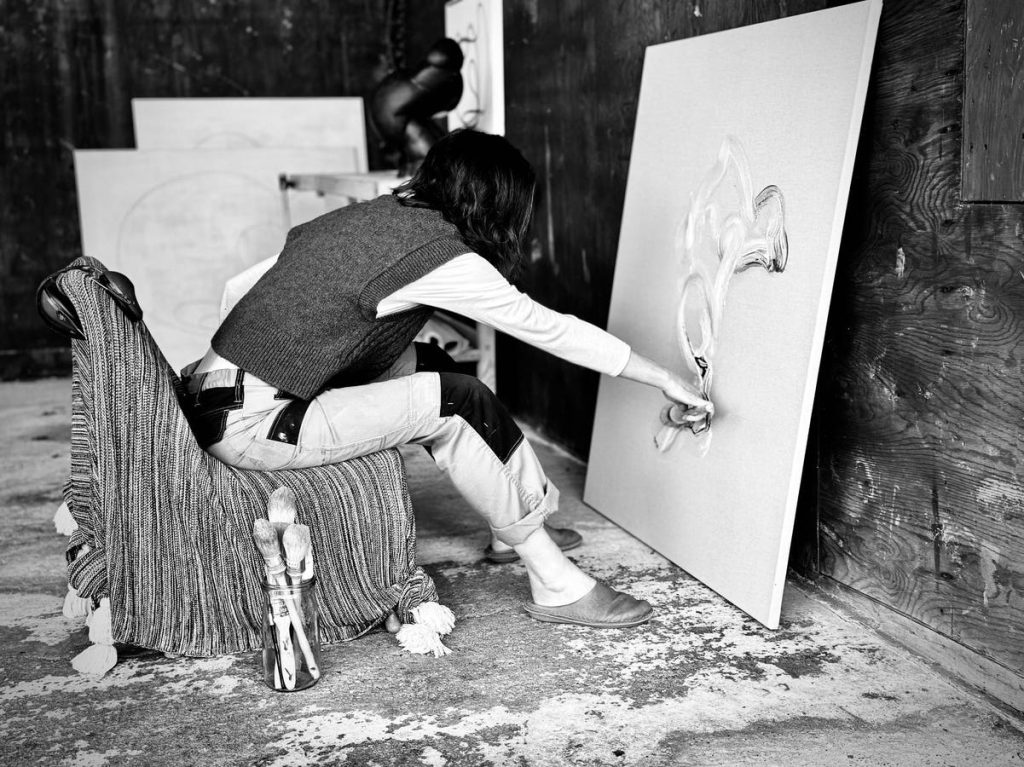

Sculptor Joanna Allen creating “psychomorphs” in her Dorset studio

Joanna Allen

Poetry is at its most successful when it expresses the feelings we struggle to voice. How often are we stuck for the right words, stumbling through sentences like we’re grasping in the dark, trying to give colour and shape to our emotions… only to read a line that so perfectly sums up our experience it feels like the writer has reached through time and space and plucked it straight out of our hearts?

Such talent is rare, but speaking to the most profound layers of our humanity is not solely the preserve of wordsmiths. Joanna Allen is a sculptor and visual artist whose work gives body to some of our most complex emotions, from safety to self-love.

“The subject matters are layered, psychologically complex.”

Bowman Sculpture, a gallery in St James’s, London, that deals with 19th century to contemporary sculpture, presented Joanna Allen’s debut solo exhibition in May 2025, titled Subconscious Playground. It’s a show that the artist and gallery have been working on together for over four years.

Joanna Allen and Mica Bowman attend a private view of “Subconscious Playground”, the debut solo exhibition by sculptor Joanna Allen, at Bowman Sculpture on April 30, 2025 in London, England. (Photo by Alan Chapman/Dave Benett/Getty Images)

Alan Chapman/Dave Benett/Getty Images

“My mother, Michele Bowman, has an incredible eye,” shares director, Mica Bowman. “She brought artists like Hanneke Beaumont and Helaine Blumenfeld into the gallery when she founded the contemporary side of Bowman Sculpture a little over twenty years ago, with my father Robert Bowman.” It was a friend of hers that initially shared Allen’s Instagram profile, “then my mum sent it to me, saying, ‘you need to see this.’”

Mica Bowman was captivated. “Something about the work instantly resonated. I rarely take on new artists, as the gallery program is already very full and we’re a relatively small operation. But with Joanna Allen, I immediately asked to discuss representation.”

Allen is the kind of rare find that dealers dream of. “As anyone in the art world will tell you,” Bowman adds, “it’s incredibly rare to find someone who feels genuinely original. Allen has that thing, that mad genius quality where creativity just pours out of her.”

“Horizon” by Joanna Allen, polished brzone with charcoal patina

Bowman Sculpture

With a background in graphic design and art direction, Allen left this commercial world in 2016 to fully focus on her own practice. A period of intense training followed: with Simon Cooley in the UK, Eudald De Juana and Robert Bodem at the Florence Academy of Art and Grzegorz Gwiazda at the Barcelona Academy of Art. “This was crucial,” Allen explains, “it helped me develop a strong foundation in understanding the figure and mastering the intricacies of form.”

“Allen has that thing, that mad genius quality where creativity just pours out of her.”

Subconscious Playground is testament to the talent she has finely tuned over these past years. Although this is her first show, Allen’s artistic trajectory has already passed through several phases—all of which are represented. Figurative and abstract works both feature, and occasionally seem to be in dialogue. The globular segments of the abstract piece, Complexing, could be a kind of smudging, a devolving, of the pregnant and engorged curvilinear silhouette of an earlier figurative sculpture, Monument.

(L) “Monument” and (R) “Complexing” both in bronze

Bowman Sculpture

Heads are a recurrent theme— which feels apt, given Allen’s cerebral nature. In fact, she is so rigorously analytical, that her latest experiments in making have sought to shut this part off completely. “I practice drawing blindfolded during meditation, to counterbalance the deliberate process of modelling figurative works,” she shares. While in this state, Allen creates marks she’s dubbed “psychomorphs”.

“This method allows me to access a deeper part of myself, one that lies beyond the constraints of conscious perception,” she explains. These sketches, mainlined from her psyche, have been “revelatory” to her practice, and are the starting points that underpin her abstract works.

“Shadow” by Joanna Allen, bronze with charcoal patina

Bowman Sculpture

Most of her figurative heads function as metaphors for big ideas that lead us down introspective alleyways. The sculpture Shadow is at first glance a face with a fringe or visor shading the eyes, but upon closer inspection, it’s an adult cranium sitting like horse’s blinkers atop the head of a smaller child.

Allen was harnessing childhood memories of feeling insubstantial around adults, though the piece also raises questions of how grown-ups can narrow a child’s outlook, or how we can armour ourselves against psychological onslaughts.

Subconscious Playground is testament to the talent she has finely tuned over these past years.

Consumption Pattern is formed of two identical bronze heads balanced together almost as though they were looking into each other’s eyes. It’s intimate, with the title seemingly asking us to confront our vanities, or the masks we wear. As Bowman sums up, “the subject matters are layered, psychologically complex.” The artist’s choice to keep eyes lowered or closed in many of the heads emphasises the reflective, inward-looking element prompted by the titles.

“Consumption Pattern” in the window of Bowman Sculpture

Sky Sharrock

This, alongside Allen’s sheer skill in reproducing physiognomy, results in an emotional depth so intense it is uncomfortable at times. These are works that worm their way under your skin and gnaw at the anxieties, tensions and little fears that live there. They feel personal to Allen, and somehow, she also reaches into our shared human experience, of being a child in an adult’s world for instance, drawing out these memories that live in each of us, and holding them up to the light.

And yet, Allen’s oeuvre never crosses over into the distressing, monstrous or shocking. With her strong foundation in figurative sculpting, she is able to articulate conceptual ideas through traditional techniques which make her work, for want of a better phrase, simply beautiful. It is this, I believe, that creates the emotional, answering echoes between her work and her audience.

Allen is the kind of rare find that dealers dream of.

There are two pieces in the exhibition that make use of installation and new media; a decision that intrigued me, given the gallery’s focus on a classical approach to sculpture. The Observer and the Observed shows two chairs (a collaboration with textile artist Yuliya Surnina) positioned to face each other in a dimly lit room, with an audio of Allen’s voice.

“It invites the viewer directly into her creative space,” explains Bowman, “it asks you to try and find that same internal stillness she draws from, to imagine what it’s like to sit in that chair, hold the brush to the canvas, eyes closed, and create with nothing but the vast, uncharted space of your subconscious to guide you. It’s quietly powerful.”

This is a clever bit of curation that encourages visitors to get to know Allen, still an emerging artist, beyond her sculptures. “I was just there to guide how the work could be communicated to an audience. There was a natural understanding between us—she created a language and somehow, I already knew how to speak it,” says Bowman.

“Psychomorph” painting that evolved into the sculpture “Afterimage”

Joanna Allen

And yet the preparation for this show must not be underestimated. When first introduced to the gallery, none of Allen’s pieces had been cast in bronze. “They were made from builder’s plaster,” Bowman shares, “which is unusual. Most artists would work in a specific sculptor’s plaster, but this felt very true to her—unconventional, instinctive, and completely unique.”

In the years it took to put together the exhibition, Allen worked closely with the foundry to produce patinas, including creating an extraordinary translucent patina that allows the original bronze to show through before fading into more traditional brown or black finishes. “Bronze carries a significance that goes beyond its aesthetic appeal,” Allen says, “It has been a medium for millennia and connects my work to that rich lineage of artists and artisans who have come before me.”

“Afterimage” by Joanna Allen, polished bronze

Bowman Sculpture

Beyond the material, Allen’s work is already being positioned within art history and some of its more powerful legacies. Her preoccupation with the inner workings of the mind have seen her dubbed a “contemporary Surrealist”. The parallels are there: Allen’s “psychomorphs” are reminiscent of Surrealist automatic writing, and she is undeniably concerned with psychology.

It is particularly fitting that Allen’s solo show debuted just after the centenary of Surrealism in 2024, marking a hundred years since André Breton penned the movement’s manifesto. Yet Allen does not quite have the profile of one of Surrealism’s enfant terribles, with their sexual dreamscapes and overt political ripostes.

As Bowman notes, “her work sits within the legacy of Surrealism, yes, but the ideas she explores—and the way she expresses them—are truly her own.” Allen’s work feels more contained; she is plumbing the depths of her own psyche and traveling inward, seeing how far she can go. Therein is her “subconscious playground” of the exhibition’s title.

“Honestly, there was enough for a full retrospective at the Tate, and that’s exactly where I see her work heading.”

“All my works are anchored in the question of what makes us us. Cindy Sherman does this really well. Her work is a brilliant visual exploration that brings us closer to understanding what it feels like to exist.”

In fact, no art genre grafts very neatly onto Allen. But if I had to draw a comparison, perhaps I would enlist Wassily Kandinsky. Considered the father of abstractionism, his metaphysical tract, Concerning the Spiritual in Art argues that art should communicate inner meaning, while artists should work in response to “internal necessity”, answering a calling to create. This feels very much in the spirit of Allen, who’s primary compulsion is so obviously to make.

“I remember visiting her studio and realizing we’d need to cut works to streamline the exhibition. There was simply too much—too many ideas, too much material—for one show. Honestly, there was enough for a full retrospective at the Tate, and that’s exactly where I see her work heading,” says Bowman.

“Subconscious Playground” is on view at Bowman Sculpture until the 30th of May 2025.