Google DeepMind has launched a specialized artificial intelligence system designed to predict the path and intensity of hurricanes with unprecedented accuracy. In a landmark move, the U.S. National Hurricane Center (NHC) will begin integrating the experimental AI into its operational workflow for the 2025 season. The partnership, a first for the federal agency, signals a pivotal moment for weather forecasting, where AI tools are graduating from research concepts to operational assets in the global effort to provide earlier, more accurate warnings for life-threatening storms.

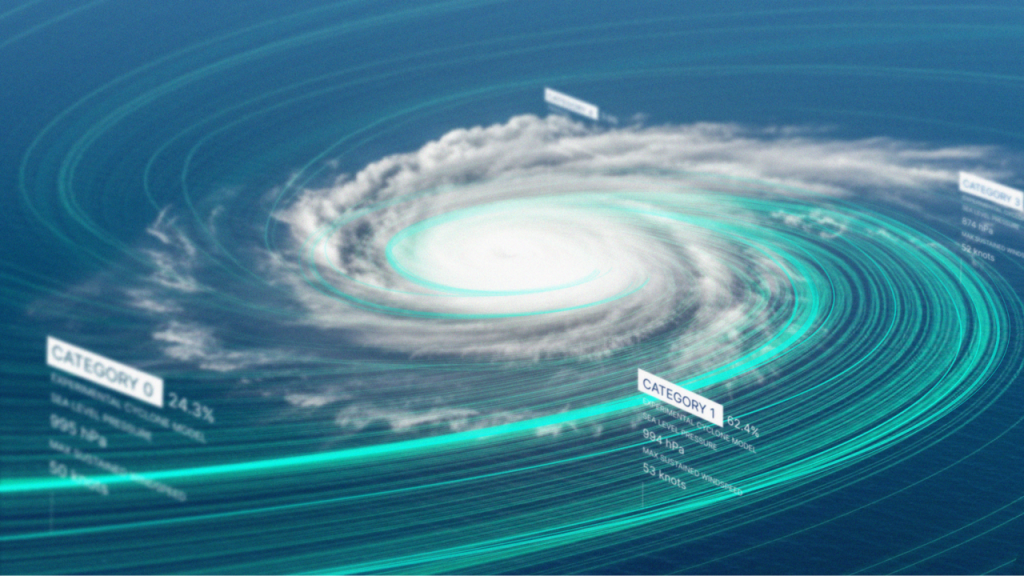

The announcement centers on a new AI model tailored specifically for tropical cyclones, unveiled alongside an interactive platform called Weather Lab. For decades, forecasters have faced a trade-off between models that could predict a storm’s path and separate, high-resolution models that attempted to predict its strength. Google’s new system claims to solve both problems simultaneously, a significant step in overcoming one of meteorology’s most persistent challenges.

This collaboration with the National Hurricane Center will put the AI’s predictions in front of expert human forecasters, allowing them to use the guidance alongside traditional physics-based models. The potential impact is enormous; more reliable forecasts delivered faster could give communities critical extra hours or even days to prepare and evacuate. The new technology could directly influence public safety during an increasingly volatile climate.

The New Front in Weather Wars: AI Speed vs. Physical Laws

The race to build a better forecast is accelerating, pitting the raw computational power of AI against the established principles of physics-based numerical models. Google’s new system can generate an ensemble forecast—a set of 50 possible storm scenarios—in approximately one minute. This speed is orders of magnitude faster than traditional supercomputer simulations, which can take hours to produce similar results.

This efficiency is a key advantage, with other projects like Aardvark Weather, from the University of Cambridge and Microsoft Research, aiming to run on standard desktop hardware to democratize access.

However, while AI models like Google’s GenCast have demonstrated superior accuracy in many scenarios, they still have room for improvement. Current AI systems still struggle with predicting small-scale, local events like tornadoes and are not as proficient at forecasting specific metrics like wind speed. This is because the models are essentially powerful pattern-recognition systems trained on historical data.

This limitation highlights why traditional physics-based models remain indispensable. Experts from ETH Zürich argue that because these older models are bound by the laws of physics, their processes are more transparent and trustworthy, which is crucial for long-term climate projections.

This has led some, including Google itself, to explore hybrid approaches like NeuralGCM, which blends machine learning with conventional atmospheric physics to get the best of both worlds.

From Cloud Providers to Climate Forecasters: Big Tech’s Weather Takeover

The Google/NHC partnership is the latest and perhaps most significant example of a broader trend: Big Tech is rapidly moving into the science of meteorology. What began with providing cloud infrastructure to research institutions has evolved into a full-fledged innovation race. Companies are now developing their own proprietary forecasting models and forming key partnerships with the very government agencies they once merely supplied.

Microsoft has been a major player, developing models like Aurora for atmospheric pollution and achieving recognition for its long-range forecasts. Meanwhile, Nvidia has unveiled its CorrDiff model for ultra-high-resolution local forecasting, and a joint effort between NASA and IBM produced the open-source Prithvi WxC model.

The scope of these ambitions is even expanding beyond terrestrial weather. A public-private partnership can provide wide-ranging benefits, as Google Public Sector is now working with the nonprofit Aerospace Corp. to apply its AI tools to forecasting space weather and geomagnetic storms.

While these high-profile collaborations with tech giants capture headlines, government agencies like NOAA are also forming partnerships with smaller, specialized firms to optimize a vast NOAA-managed archive of observational data for AI training. Addressing the sensitive topic of private companies entering a traditionally public domain, Google DeepMind research scientist Peter Battaglia affirmed the company’s goal is to contribute to what has long been “viewed as a public good” and to “partner with the public sector.”

The Achilles’ Heel: AI’s Thirst for Endangered Public Data

This entire AI-driven transformation, however, is built on a foundation that is showing signs of cracking. These complex models are trained on decades of historical weather data, much of which comes from publicly funded archives managed by agencies like NOAA. Yet, as AI’s dependence on this data grows, the institutions that provide it are facing an existential threat.

Proposed budget cuts and significant staffing shortages have plagued NOAA and its National Weather Service (NWS). The situation grew so dire that five former NWS directors issued an open letter warning of the potential for a “needless loss of life.”

This sentiment was echoed by Richard Turner, a Cambridge University professor who told The Financial Times, “The community hasn’t — surprisingly, in my view — woken up to this danger yet… Yes, there is massive concern on this and I think the cuts are very dangerous at a time when the climate really is changing.”

The agency is now scrambling to deal with the realities of this crisis. After losing approximately 550 employees since January 2025, the NWS was granted an exemption to the federal hiring freeze to fill 126 “critical vacancies” as the hurricane season begins. But for many on the inside, it may be too little, too late.

Some forecast offices are reportedly on “life support,” with staffing for meteorologists down 30% in critical regions like Florida. James Franklin, a former branch chief at the NHC, warned the effort was like “shuffling the deck chairs on the Titanic,” adding, “You fill a hole somewhere, and you’re creating one somewhere else.”

This paradox defines the current moment in weather prediction. The Google/NHC partnership represents a monumental leap forward in our technological ability to forecast nature’s most destructive storms, exemplified by the model’s impressive retrospective performance on Hurricane Otis.

In that case, DeepMind engineers believe their model would have likely provided an earlier signal for the storm’s potential risk had it been available at the time. As Tatyana Deryugina, a finance professor at the University of Illinois, noted, “If people are gonna decide whether they evacuate or not, how much they trust the forecast is gonna matter.” That trust is built not just on the sophistication of an algorithm, but on the reliability of the data it learns from.