Almost a fortnight ago, a wave of pastel-coloured, soft dreamscapes took over our social media timelines. These portraits, with their glimmering eyes, lush scenery, and whimsical touches, were reminiscent of the deft hand of Studio Ghibli co-founder Hayao Miyazaki, the creator of enduring masterpieces such as Spirited Away and My Neighbor Totoro.

But as timelines filled with Ghibli-inspired creations, a thornier conversation began taking root. Some critics and legal observers raised questions about the permissibility of using prompts like ‘Ghibli-style’ or ‘anime-inspired’ in AI tools. Is this art, homage, or something closer to infringement? Could AI tools or their users be held legally accountable for mimicking an artistic style?

Style versus substance

“The style of an artist is not copyrightable,” says Shatrajit Banerji, Partner Designate at law firm Cyril Amarchand Mangaldas. “A particular painting can be copyrighted. But when I talk about a style — like the romanticism of Ghibli’s aesthetic — that’s not something that can be protected.”

Ankit Sahni, IP and technology law counsel, clarifies the nuance under Indian law with a hypothetical example. “While Japan is known for multiple animation styles — anime, hentai, etc — Studio Ghibli’s aesthetic is quite distinct. If an AI output unmistakably evokes Ghibli and not, say, Pokémon or Transformers, then under the ‘unmistakable impression’ test laid down by the Indian Supreme Court in RG Anand v. Deluxe Films, that could still amount to infringement,” he says.

So, where does the legal line lie?

Experts say that the core issue rests in what copyright law is designed to protect.

“Under the Copyright Act, 1957, copyright protects original literary, dramatic, musical, and artistic works, including specific artworks like paintings or sculptures,” says Dr Hema Krishnamurthy, a copyright scholar and professor at Christ University. “However, it does not protect ideas, concepts, themes, methods, techniques, and styles.”

In other words, artistic styles fall outside the protective umbrella of copyright. “You can create works in the style of another artist, but you cannot copy their specific artwork,” Krishnamurthy adds.

Story continues below this ad

Sahni, however, believes the issue is not as clear-cut, especially when it comes to how AI models are trained. “Section 14 of the Indian Copyright Act defines copyright to include reproduction, including storage of a work in any medium.” So, if a model has been trained on Ghibli content and that training involved storing and reproducing copyrighted works without consent, that could amount to infringement under Indian law, he says.

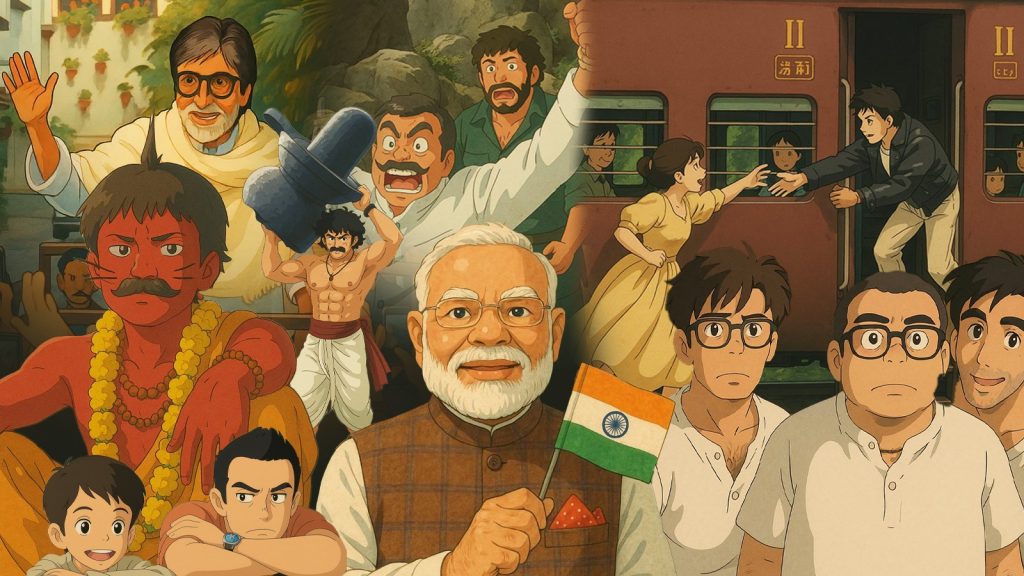

Nobody asked for Bollywood movie scenes in Ghibli style — but here they are. pic.twitter.com/umiDAA7LNu

— Vivek Choudhary (@ivivekch) March 26, 2025

Traditional art and technological imitation

These questions become even more fraught when traditional Indian art styles enter the conversation. Folk forms like Madhubani, Gond, and Miniature paintings carry strong regional and cultural identities, passed down through generations. Could an AI-generated image that mimics such styles be protected? “The answer would be no,” says Banerji.

But there is another layer of potential protection: Geographical Indications (GIs). These are a distinct form of intellectual property that safeguard products with specific regional origins and reputations. “A GI tag in India protects products that have a specific geographical origin and possess qualities or a reputation due to that origin,” said Pallavi Singh, Partner at Cyril Amarchand Mangaldas. “While a GI tag can help prevent the misuse or false representation of traditional art forms, it does not specifically prevent AI from reproducing or generating art based on those styles.”

Singh notes that legal action might be possible if an AI’s output closely resembles original works to the point of infringement, but GI protection, on its own, cannot stop AI from imitating an art style.

Sahni says, “These are historic community art styles. GI protection only kicks in when there’s a misrepresentation of origin. So if an AI-generated artwork doesn’t claim to be an ‘authentic’ Madhubani painting, it may not breach GI rules, but the ethical debate remains.”

Story continues below this ad

Artists, however, have voiced concern over the growing tension between technological advancement and artistic integrity. “We are yet to understand what AI is all about. It is not very clear. My worry is that people may take advantage of it and dupe people. Already, there are issues of authenticity and provenance. AI is just some kind of phantom technique. We are dealing with copyright, provenance, and fakes,” says Ina Puri, writer, art curator, documentarian, and collector.

Ghibli images, posted by the Government of India’s official MyGov account on X, depicted PM Modi shaking hands with US President Donald Trump. (X@@mygovindia)

Ghibli images, posted by the Government of India’s official MyGov account on X, depicted PM Modi shaking hands with US President Donald Trump. (X@@mygovindia)

A jurisdictional puzzle

Jurisdiction is another complication. OpenAI is based in California, a jurisdiction known for its relatively broad interpretation of “fair use”.

“Copyright and IP rights are jurisdictional,” Banerji points out. “You might have protection in India, but that doesn’t automatically extend to the US or Europe.”

Sahni says that OpenAI has taken the position in Indian court that because its servers are based in California, and the training occurred under US law — which allows such use — it should not be liable in India. “They’re arguing that because the copying and training happened legally in their jurisdiction, Indian courts shouldn’t have a say,” Sahni says. “But that’s a question the courts must decide.”

Story continues below this ad

And while Japan has carved out a text-and-data-mining exception, that too complicates enforcement: “It’s possible OpenAI trained its models on Ghibli-style art in Japan, relying on that exception,” he says.

Banerji notes that while international treaties like the Berne Convention and TRIPS Agreement exist, enforcement depends on domestic law and bilateral agreements. “There is no international copyright body that can enforce these rights globally.”

The global legal landscape

Different countries are approaching the intersection of AI and copyright in strikingly varied ways. While Japan and the UK have introduced specific exceptions for non-commercial data mining, India has not, Sahni says.

“In the European Union, there is a proactive emphasis on transparency and ethical considerations,” says Singh, referencing the proposed AI Act, which classifies AI systems by risk level and imposes stringent oversight on high-risk applications.

Story continues below this ad

China, she adds, has adopted a centralised approach through the Interim Measures for Generative AI Services, requiring AI providers to respect intellectual property rights. In the UK, the Thaler v. Comptroller General of Patents decision underscored the legal system’s reluctance to treat AI as a creator.

In the US, a high-stakes lawsuit — New York Times v. OpenAI — is testing the limits of “fair use” in the context of AI training, echoing the concerns at the heart of the Ghibli-style debate.

“As AI’s creative capacities evolve, legal systems struggle to adapt,” Singh says. “There’s a critical gap between technological advancements and existing intellectual property laws.”

OpenAI’s position: Style is a fair game

Asked to comment on the ‘Ghibli-style’ debate, OpenAI told news agency AFP that it currently prohibits image generation “in the style of individual living artists” but does allow broader studio styles.

Story continues below this ad

“We continue to prevent generations in the style of individual living artists,” a company spokesperson said, “but we do permit broader studio styles, which people have used to generate and share some truly delightful and inspired original fan creations.”

The company said it would continue refining its models based on user feedback and ethical considerations.

What can Indian artists do to protect their work?

Sahni asserts the need for legal clarity and possible amendments to Indian copyright law to address AI-era challenges. “India still lacks specific exceptions or regulations around AI training and style replication,” he says. “Until that happens, we’re left interpreting decades-old laws for brand-new technology.”

Singh offers practical steps for artists navigating this evolving landscape. “Indian artists can protect their art through several mechanisms under Indian copyright law. Registering works with the Copyright Office establishes ownership and secures legal rights against unauthorised reproduction. While registration isn’t mandatory, it strengthens your case in legal disputes.”

Story continues below this ad

Amid ongoing debates around AI’s impact on Art, Puri lists recent achievements in Indian art — like the Rs 118 crore sale of MF Husain’s Untitled (Gram Yatra), the Rs 61.8 crore sale of Tyeb Mehta’s 1956 oil on canvas during his centenary year, and Arpita Singh’s solo retrospective at London’s Serpentine — as reasons to celebrate, not cloud with ambiguity. “Indian art is doing brilliantly… But until and unless there are strict laws, this (AI) will muddle the market. We’re all in the art world and wondering how it will affect us. AI is writing essays and making art, but it still lacks the human hand and heart.”