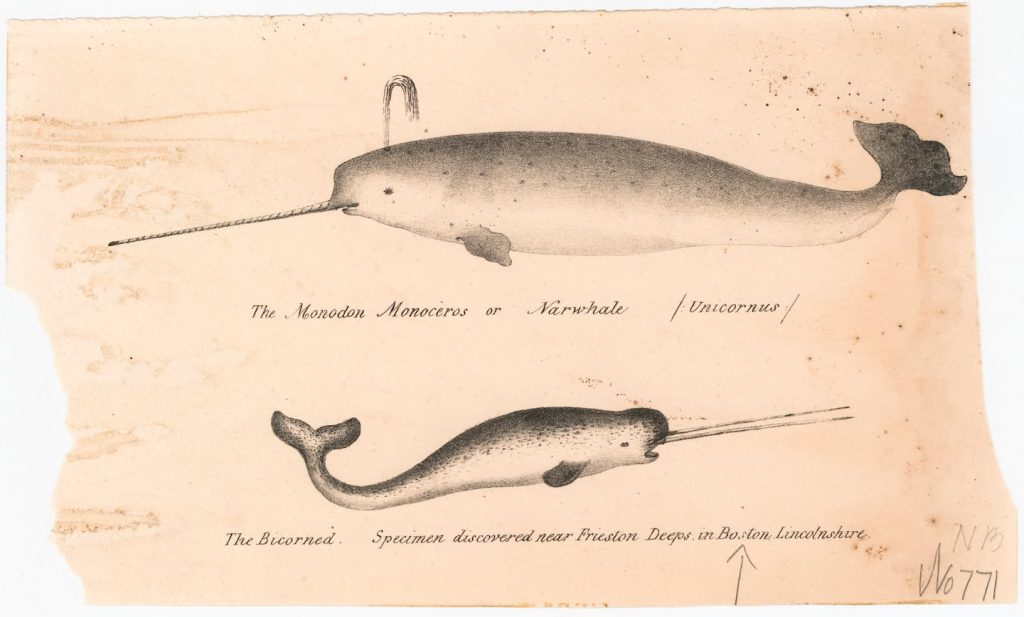

Narwhals loom large in the imagination. How could they not, being the inspiration for unicorns. They’re also real, and thus firmly in the realm of science. That’s the other part of the exhibition. It’s conceptual and stimulating: a kind of case study in the nature of our knowledge about nature. In this particular case, that natural knowledge concerns whales.

MIT’s Florencia Pierri and Elisabeth (Libby) Meier curated the show. The wall texts they provide are both lively and informative. It’s pointed out, for example, that certain images recur in the show. That’s not to make some compare-and-contrast point. Rather, it’s because for centuries images of whales were so few (and inaccurate).

The best opportunities for observation came with whale beachings. But beachings not only presented the creatures away from their natural habitat. The whales were dead and decomposing. This meant accuracy was not always the order of the day. The subject of Hendrick Hondius’s 1598 print “Beached Whale at Berckhey” looks positively merry. The imputation of personality is delightful, but more a foreshadowing of Disney than an exercise in scientific inquiry.

The path from fantasy (“Here be monsters”) to science (whales aren’t fish, they’re mammals) owed something to curiosity, of course, but even more to commercial considerations and advances in nautical technology. As whaling developed as an industry, human encounters with the creatures vastly increased in number and proximity. And as shipbuilding and navigation became more sophisticated, it became less difficult, if never easy, to encounter whales in situ.

The idea of whales as a subject of informed study, as well as a source of wonder, is nicely conveyed by “Skeleton of a Greenland Whale in the Royal College of Surgeons,” which ran in The Illustrated London News in 1866. Even as these medical men are gazing about this mighty skeleton they are themselves being gazed upon by the many readers of that publication.

Is it a stretch to impute a sense of wonder to the dozen or so top-hatted gents (no ladies present, thank you very much) as they gaze upon the bones of this leviathan? Surely not, and that may be the most pleasing point implicit in “Monsters of the Deep.” Even as knowledge of whales became so much more accurate and extensive, these creatures became, if anything, even more wondrous and astounding than when they were best known for swallowing Jonah.

The great fish in the Book of Jonah is anonymous. Herman Melville created the most famous, if fictional, cetacean monster of the deep — monster of the book, too. Interested readers are well advised to head up to Salem, for the Peabody Essex Museum’s “Draw Me Ishmael: The Book Arts of Moby Dick.” It runs through March 29, 2026.

Also, the MIT Museum will be hosting a panel discussion inspired by “Monsters,” Tuesday, from 6 p.m.-8 p.m. “Seeing and Understanding the Unknown” features astrophysicist Erin Kara, sonar pioneer Martin Klein, and the show’s curators.

MONSTERS OF THE DEEP: Between Imagination and Science

At MIT Museum, 314 Main St., Cambridge, through January. 617-253-5927, mitmuseum.mit.edu

Mark Feeney can be reached at mark.feeney@globe.com.