In the aftermath of Hiroshima, many of the scientists who built the atomic bomb changed the way they reckoned time. Their conception of the future was published on the cover of The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, which portrayed a clock set at seven minutes to midnight. In subsequent months and years, the clock sometimes advanced. Other times, the hands fell back. With this simple indication, the timepiece tracked the likelihood of nuclear annihilation.

Although few of the scientists who worked on the Manhattan Project are still alive, the Doomsday Clock remains operational, steadfastly translating risk into units of hours and minutes. Over time, the diagram has become iconic, and not only for subscribers to The Bulletin. It’s now so broadly recognizable that we may no longer recognize what makes it radical.

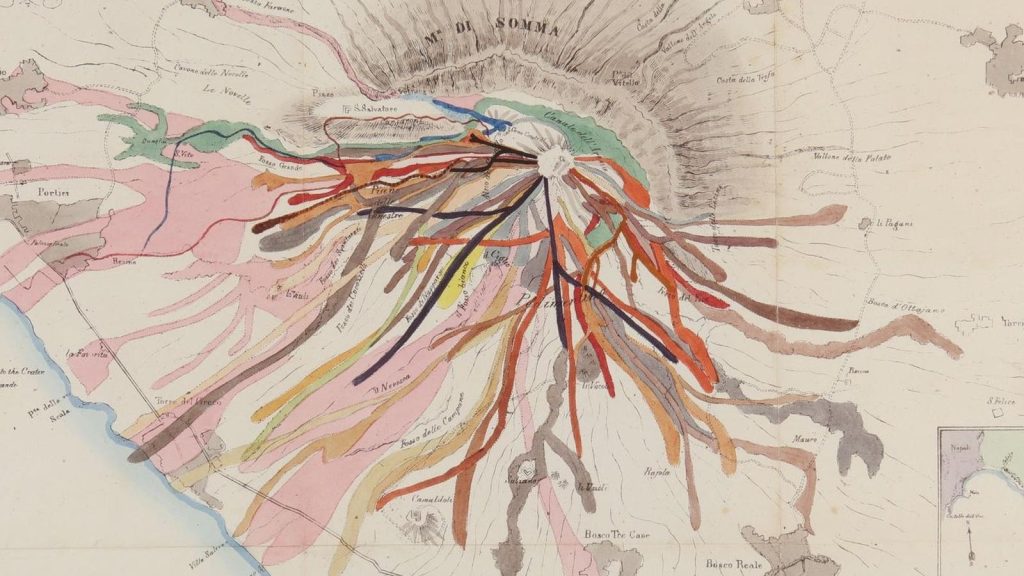

John Auldjo. Map of Vesuvius showing the direction of the streams of lava in the eruptions from 1631 to 1831, 1832. Exhibition copy from a printed book In John Auldjo, Sketches of Vesuvius: with Short Accounts of Its Principal Eruptions from the Commencement of the Christian Era to the Present Time (Napoli: George Glass, 1832). Olschki 53, plate before p. 27, Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Firenze, Firenze. Courtesy Ministero della Cultura – Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Firenze. Any unauthorized reproduction by any means whatsoever is prohibited.

Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Firenze

A thrilling new exhibition at the Fondazione Prada brings the Doomsday Clock back into focus. Featuring hundreds of diagrams from the past millennium, ranging from financial charts to maps of volcanic eruptions, the exhibition provides the kind of survey that brings definition to an entire category of visual communication. Each work benefits from its association with others that are manifestly different in form and function.

According to the exhibition curators, a diagram as “a graphic design that explains rather than represents; a drawing that shows arrangement and relations”. In other words, a diagram is a picture with a purpose, and its purpose is at least one degree removed from the image presented. It can be understood only through transposition. If it corresponds to reality, it never does so literally.

These qualities, which show how complex diagrams are as a mode of expression, are evident even when you look at some of the earliest examples in the exhibition. For instance, many of the anatomical charts from Medieval times and the Renaissance are inscribed not only with parts of the body but also with constellations. Astrological signs were believed to influence bodily functions. (Aries was typically associated with the head, Taurus with the neck, Gemini with the lungs, Scorpio with the groin.) The influences of the stars were physically invisible. Fitting the signs to anatomical features, diagrams depicting the so-called ‘zodiac man’ provided pictorial guidance to medical practices such as bleeding, while simultaneously reenforcing the animating idea of man as the cosmos in microcosm.

The practice of superimposing disparate information has outlasted scientific acceptance of zodiac men. In fact, juxtaposition has advanced many disciplines by testing the explanations the graphics purport to illustrate. Diagrams give specificity to hypotheses, subjecting them to collective scrutiny. Presenting correlations across multiple dimensions, they expose meaningful patterns as well as false associations.

The Fondazione Prada exhibition provides several compelling examples from epidemiology, including one of the most famous maps in the history of medicine: the diagram that revealed the cause of a cholera. In 1854, Dr. John Snow charted cholera cases in relation to the locations of London’s neighborhood water pumps, showing a geographic overlap that revealed cholera to be a waterborne disease spread through contamination. His theory – now accepted as scientific fact – ran contrary to the medical consensus that cholera was a poisonous vapor, an illness contracted by breathing.

The older hypothesis, known as miasma theory, had also been charted. One especially impressive diagram was prepared by Dr. Henry Wentworth Acland, who showed British cholera cases in relation to temperature, precipitation, and barometric pressure. Although Acland’s bar chart did not disprove the theory he sought to bolster, it provided little explanatory power, far less than was conveyed by Snow’s famous map. Attempting to show that cholera was modulated by climate, Acland inadvertently contributed to the miasma’s demise.

The contrast between Acland’s graph and Snow’s map demonstrates both the value of data and the significance of format. Explanations are aesthetically experienced. Snow could have reached his conclusion with bars of different lengths instead of geographic coordinates, but the cause of cholera probably wouldn’t have been as readily apparent, and the presentation certainly wouldn’t have been as compellingly persuasive.

Of course, persuasion isn’t always felicitous. When data are carelessly used or callously manipulated, persuasiveness can be downright dangerous, the crux of political propaganda. Assessing a diagram requires critical thinking. But the Prada exhibition presents at least as many instances in which diagrams have advanced political principles and positions with incisiveness generally lacking in political discourse.

W.E.B. Du Bois. Conjugal condition of American Negroes according to age periods, c. 1900. Exhibition copy of a statistical chart illustrating the condition of the descendants of former African slaves now in residence in the United States of America, Atlanta University. Ink and watercolor on paper. Daniel Murray Collection, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Courtesy Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C., Daniel Murray Collection

Library of Congress,

One of the greatest practitioners of the 20th century was the sociologist and civil rights activist W.E.B. Du Bois. In a set of diagrams prepared for the 1900 Paris Exposition, Du Bois showed the fortunes of Blacks in the United States since emancipation. What is most striking about this series is the impact of the work as a whole. This is all the more surprising given that each diagram is highly particular, practically sui generis. One shows the “assessed value of household and kitchen furniture owned by Georgia Negroes”. Another shows “race amalgamation in Georgia based on a study of 40,000 individuals of Negro descent”. There are charts tracking literacy, migration, and taxation.

These charts do not overlap in the way that Snow superimposed cholera and water pumps. They could not comprehensibly be assimilated into a single diagram. Instead they use a shared visual language to connect different dimensions of the African-American experience, constructing a multifaceted reality with novelistic acumen. Each chart is descriptive. The explanatory power of Du Bois’ project emerges as the eyes move restlessly between them.

The Doomsday Clock is also political, picturing conditions that collectively contribute to the irreducible reality of a world in peril. In recent years, the editors of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists have added factors ranging from climate change to artificial intelligence into their temporal calculus. All of these explain present conditions and must inform political decisions.

Yet there is an important difference between the cover of the Bulletin and Du Bois’s contribution to the Paris Exposition. If the former has the expository breadth of a graphic novel, the latter has the semantic compression of a concrete poem.

Our command of apocalyptic technologies necessitates a new kind of relationship with history, a responsibility for all possible futures that is visually expressed in the restless movements of the clock’s hours and minutes. What the Doomsday Clock lacks in mechanistic explanation of risk, the graphic makes up for by exposing our influence over the end of time. Each and every person is an existential threat in microcosm.