There’s no such thing as a typical day for Angela Eichhorst.

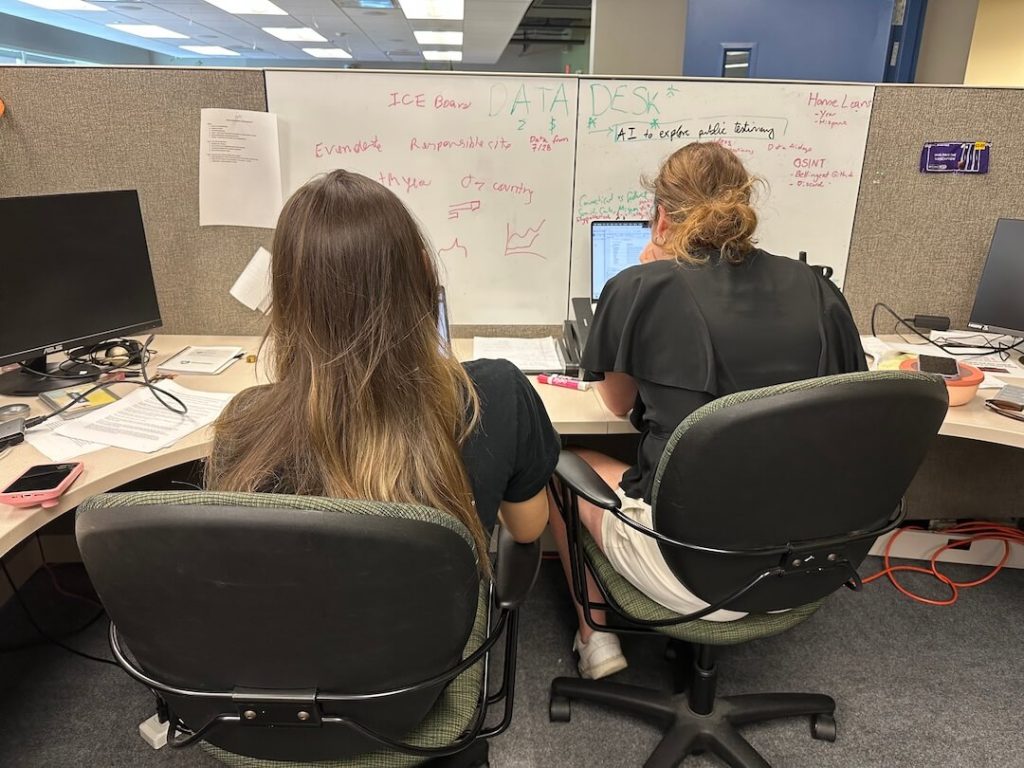

The Connecticut Mirror’s new artificial intelligence data reporter and product developer is trying to figure out how to tell stories that were previously impossible because of the volume of documents or deadline pressure.

In Connecticut, where news is often made in municipal meetings, the nonprofit’s beat reporters can’t make it to all 169 different towns, Eichhorst said. One of her goals is to generate leads and get material from those meetings to reporters using AI tools.

Critics warn that AI could replace journalists as newsrooms look to cut costs. But CT Mirror is among a new crop of small nonprofit outlets using the technology to complement reporting and fuel investigations by churning through documents, cutting through legislation and parsing historical records.

At a time when news budgets are tight, especially at smaller nonprofits, AI may be a tool to help handle the tedious but essential work of tracking legislation and transcribing meetings, said Andrew Haeg, network product manager at the Institute for Nonprofit News.

However, AI adoption among INN member newsrooms is uneven, Haeg told Poynter and IRW in a recent interview. One-third of INN’s members used AI “in ways that benefit their organization” in 2023, according to INN’s 2024 Index survey of its members. In 2024, INN estimated that more than half of its 500 members would be using AI this year.

Most of those outlets are using AI in the back office, including audience engagement, fundraising and outreach, or for routine tasks such as transcription, Haeg and INN researcher Ha Ta told Poynter and IRW.

While those uses can be powerful, Haeg said, there’s more that small newsrooms can do to benefit from AI, including repurposing content for multiple formats or automating community event calendars.

“In order to fill (news) deserts back in, we have to think not in terms of trying to rebuild newsrooms of the past,” Haeg said, adding that newsrooms “can punch way above their weight” if they’re using new tools in a smart way.

Seth Lewis, the Shirley Papé Chair in Emerging Media and journalism program director at the University of Oregon, argues that journalists should treat AI as a tool to expand the very possibilities of reporting.

Generative AI poses “a fundamental disruption to journalism as a practice and profession,” said Lewis, who has studied how changes in technology impact the news for about the last 20 years.

“The rise of generative AI has really brought forward how technology has really moved into a creator role that was once viewed to be as distinctly human,” Lewis said, pointing to what he calls “answer engines” — chatbots.

“Probably one opportunity is for news organizations to say, ‘To what degree are we an answer engine?’” Lewis said.

The Washington Post took that question literally, and developed a chatbot called “Ask The Post AI,” which does what its name suggests: the model digs through The Post’s archives to answer any questions readers might have. Stephen Busemeyer, the Mirror’s managing editor, said he’s considering the value of a similar tool for Connecticut readers.

“What if you could ask AI, ‘How does the speaker of the House get power? What other stories can I read to learn about that?’ ” Busemeyer wondered. “Isn’t that a more friendly, a more intimate invitation to readers to engage with civic life? That’s interesting to me. So if I can use a chatbot in that kind of format, I’m intrigued. Let’s talk.”

Busemeyer got that idea from a Harvard Shorenstein Center article about the intimacy of AI. He said he wasn’t sure if it was logistically or financially possible to implement a chatbot such as “Ask The Post AI.”

The Post started with a team of about five people to explore whether it could create a chatbot based on its articles, said a senior Post leader involved in the project, who spoke on condition of anonymity to discuss internal operations. The team started by creating a chatbot trained on the climate section.

Engineers developed an early version of “Climate Answers,” which Post climate reporters tested before it was released to the public in the summer of 2024. The team got feedback from readers and grew in numbers to expand the project to content across the newsroom, the Post leader said.

It took a newsroom to raise a chatbot: The entire company was asked to test a beta version of “Ask The Post AI” and teams from web design to legal came together to finalize it.

Now, the Post’s publishing tech arm, Arc XP, is making the technology available to other news organizations, which can create a similar chatbot based on their articles, the Post leader said. The project, known as “Ask The News,” has launched as a pilot program and aims to save publishers money on building and testing their own chatbots.

Exploring AI’s uses is expensive: the American Journalism Project, a nonprofit that funds local, nonprofit news ventures, supported a bulk of the costs for the Mirror’s AI reporter/developer position, Busemeyer and Eichhorst said.

It’s also tempting for news organizations to save money by replacing reporters with AI tools.

“If the incentives are there to save money, well, then it’s going to take a lot of work to resist those temptations on the part of any kind of news enterprise because of the sort of financial exigency that many of them are in,” Lewis said.

But the Mirror isn’t replacing any of its reporters with AI, Busemeyer said.

Angela Eichhorst (Courtesy)

The Mirror created Eichhorst’s position because “we just wanted to do better journalism,” Busemeyer said. If an AI tool can help readers better understand important topics, the Mirror will explore it.

“If it’s just something sparkly and even puts the readers at risk of having bad information, no, we do not,” he said. “We won’t go there.”

Busemeyer considers AI tools akin to “a very hypercaffeinated intern.”

“I know it’s going to get stuff wrong,” he said. “We will double-check everything. We will be transparent.”

He wanted to create Eichhorst’s role to explore responsible uses of AI and add value for readers. But Busemeyer said he still doesn’t know what the future of journalism looks like with AI.

“When I was talking to candidates, I would tell them that we really have no idea what we’re doing with AI and, honestly, nobody does,” he said. “We’re still totally figuring it out. So if anybody comes to me and tells me, this is how you use AI, they’re not going to get the job.”

Before Eichhorst was hired, Busemeyer, a former data editor at The Hartford Courant, developed four internal AI tools for the Mirror — what he calls his “little army.” They’re all trained on different datasets about the Connecticut government.

One answers questions about state laws. Another is trained on Connecticut’s “Blue Book,” the State Register and Manual, which is effectively an almanac of the state’s government.

For one bot, the Mirror created a database of how each general assembly member voted in 2023 and trained the AI model on that database to answer questions about voting patterns. The fourth tool analyzes reports by the state Office of Legislative Research, which are often requested by legislators looking to write a new bill.

The Mirror does “a lot of in-depth reporting on issues that somebody else is just going to cover superficially,” Busemeyer said, so AI tools are especially useful for investigations or data analyses.

A few years ago, Busemeyer investigated a story idea with a “messy, messy pile of data.” He wanted to find out if personnel transfers at a state agency were done to cover up wrongdoing.

He discovered that data about the transfers were organized in one place, and he could get them through the Freedom of Information Act. After analyzing the data, he found that there was no great cover-up, just questionable transfers, and decided to back off the story.

He recently asked ChatGPT’s model o3, released in April 2025, to find the data “hidden in the bowels of Connecticut bureaucracy” and analyze it — something similar to what he undertook manually.

The chatbot returned an “almost perfect” FOIA request, and when he handed over the data, ChatGPT “came to some of the exact conclusions that I did,” Busemeyer said. The o3 model in particular is “a great boon to journalists” because of its deep research abilities, he said.

Looking forward, Busemeyer and Eichhorst are developing a large-scale video scraping tool that will transcribe and summarize video pulled from websites. Eichhorst said she hopes the video scraper and other AI tools will be able to fit into larger workflows that help the Mirror’s journalists.

This story was produced in partnership between the Investigative Reporting Workshop and The Poynter Institute.

Correction (Aug. 28, 10:55 a.m.): The Mirror created a database of how each general assembly member voted in 2023, not 2020.