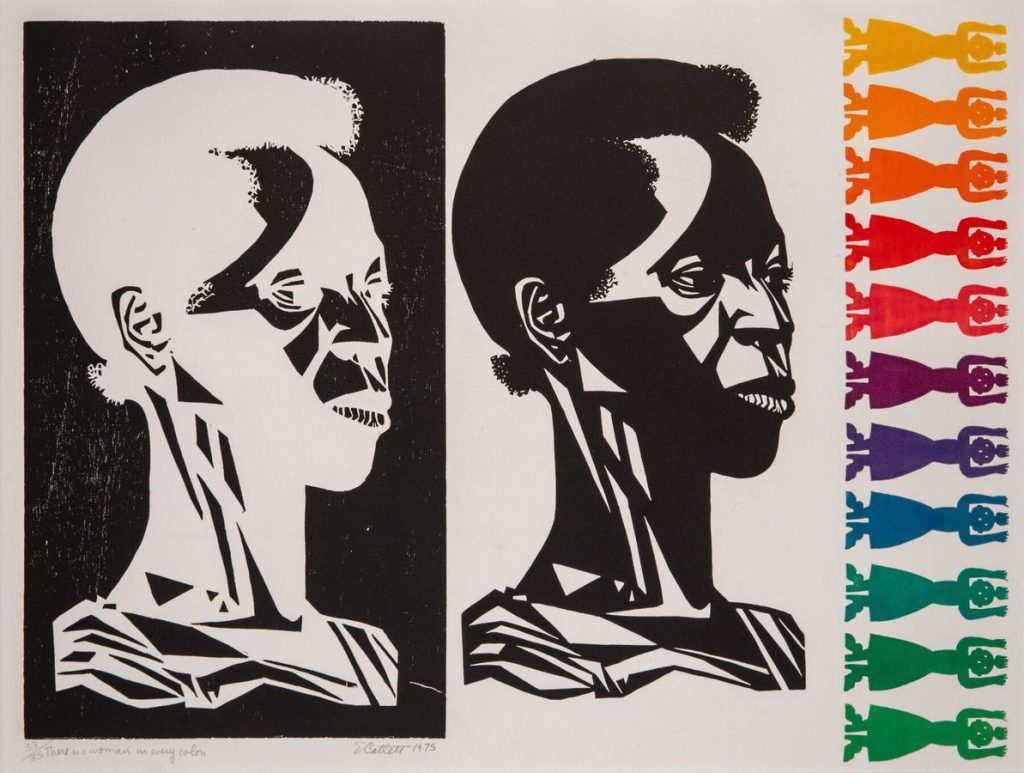

Elizabeth Catlett, ‘There is A Woman In Every Color,’ 1975, woocut/linocut sheet: 55.9 x 76.2 cm (22 x 30 in.) framed: 77.5 x 91.4 cm (30 1/2 x 36 in.). From the Hampton University Museum Collection, Hampton, VA

Alexanders Photography. © 2024 Mora-Catlett Family / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

“A Black Revolutionary Artist and all that it implies.”

Elizabeth Catlett (1915–2012) spoke those words from Mexico, having been denied a visa by the United States, her country of birth, for entry to attend and speak at a 1970 conference. Catlett was banned in the U.S.A.

Her banishment was set in motion by receiving Mexican citizenship in 1962. Pursuing Mexican citizenship was set in motion by imprisonment in Mexico in 1959. Catlett was tossed in jail for participating in a railroad workers strike, labelled a “foreign agitator” by the Mexican government. By acquiring Mexican citizenship, she couldn’t be considered a “foreign agitator” there.

But she could in America.

As soon as Catlett’s Mexican citizenship was granted, she became an outlaw on the other side of the border. The notorious House Un-American Activities Committee immediately labeled her an ‘undesirable alien’ and barred her from returning.

Catlett was swept up in the Red Scare, a mid-century mania infecting American politics seeking to prove its thesis that the government had been infiltrated by communists working to take down capitalism and democracy. Everyone with opinions left of center or anyone who’d ever run afoul of the Red Scare communist purity-testers was targeted. Most famously, the fever overtook Hollywood, but union organizers, civil rights activists, homosexuals, and artists were all prime suspects as well.

The artist’s life of activism in the United States in pursuit of equal rights for African Americans and women and her association with communist artist colleagues in Mexico–Diego Rivera, Frida Kahlo, David Siqueiros, among them–was more than enough evidence for Red Scare witch hunters to forbid her from returning to the good ‘ole U.S. of A, land of the free, home of the brave.

Catlett’s full “Black Revolutionary Artist” quote was: “I was refused on the grounds that, as a foreigner, there was a possibility that I would interfere in social or political problems, and thus, I constituted a threat to the well-being of the United States of America.

“To the degree and in the proportion that the United States constitutes a threat to Black people, to that degree and more, do I hope that I have earned that honor. For I have been, and am currently, and always hope to be a Black Revolutionary Artist and all that it implies.”

Catlett’s words give inspiration to the most comprehensive presentation ever devoted to her work in the United States, “Elizabeth Catlett: A Black Revolutionary Artist,” on view now through July 6, 2025, at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., the artist’s hometown. More than 150 works, including iconic sculptures and prints, along with rare paintings and drawings, and important ephemera, are on view.

Admission to the National Gallery is free. Government is a public service, not a for-profit enterprise.

Catlett was finally allowed to return to America in 1971 for the opening of her solo exhibition at the Studio Museum in Harlem following a lobbying effort with the State Department by friends. By 1983, she could freely travel between Mexico and the U.S. and spent part of each year in New York.

“All That It Implies”

Elizabeth Catlett, ‘Sharecropper,’ (1952) linocut. © 2019 Catlett Mora Family Trust / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

Art Institute of Chicago

What is the “all” Catlett implied about being a “Black Revolutionary Artist?”

The cost.

Targeting by your government? Banishment from your country? Jailing? Appearing on lists of “agitators.” Surveillance?

Was the “all” the work? Not just the artwork, but the activism. Tirelessly fighting oppression and racism and patriarchy and the governmental, economic, and societal systems built on them, systems carefully and historically designed to benefit the few at the expense of the many?

Yes.

“Black Revolutionary Artist” is all encompassing. More than a profession. A way of life.

Catlett lived every day of her life as a “Black Revolutionary Artist.” She lived every day of her life as the grandchild of enslaved people, both sets of grandparents. She heard those stories as a child visiting them in North Carolina.

She saw sharecropping. Her most famous individual image, 1952’s Sharecropper linocut, possesses an insight only possible from up-close observation.

“As a young artist, Catlett thoughtfully worked through and studied the art movements of her moment,” Catherine Morris, Sackler Senior Curator, Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art, Brooklyn Museum, where the exhibition debuted, told Forbes.com. “Engaging with various emergent tenets of modernism, from the geometric lyricism of Lois Mailou Jones to the Social Realism of Grant Wood; from Picasso’s Cubism to the organic abstraction of Henry Moore; from Käthe Kollwitz’s expressionistic woodcuts to the mural painting of David Alfaro Siqueiros. From these histories, Catlett developed a language that prioritized legibility and the adding of the long overlooked voices of Black women.”

Catlett’s prints of Black women, like Sharecropper, are particularly powerful. They reveal a tension around the eyes. Weariness. Wariness. Sad. Resolute. Generational trauma. Empty promises. Dreams denied. Low expectations. The eyes of her Black men don’t have that. The eyes of her Mexican women don’t have that.

Catlett witnessed the failures of capitalism. She lived through the Great Depression.

Jim Crow, too.

She organized protests as a high schooler against lynchings in Washington, D.C. She earned a scholarship to the Carnegie Institute of Technology in Pittsburgh, but her offer was pulled when administrators learned she was Black. Catlett was light skinned enough to “pass” for white, but never chose to. She did even better and went to historically Black Howard University in D.C. where she came under the influence of renowned African American educator and artist, Lois Mailou Jones.

“I admire Elizabeth Catlett’s innate understanding of herself as part of a long history of activism,” Morris said. “Catlett understood the job of her creative work was to keep the history that came before her alive and vital in the present while also supporting and championing the generations of activists and artists who came after her. Catlett’s art proves her determination to directly address injustices she saw in the present, while also linking them to the past in order to order to offer a roadmap for the future.”

Catlett’s fusion of art and politics was cemented in 1946 when she moved to Mexico. She was pursuing printmaking at the highly regarded artist collective Taller de Gráfica Popular, then labeled a “Communist front organization” by the American Embassy.

She became deeply involved with leftist cultural circles in Mexico City and Cuernavaca. She recognized how the Mexican Revolution and the Civil Rights Movement in America were connected–how the struggle of all marginalized, colonized, abused, disenfranchised people fighting the powerful across the globe were connected.

“Art is only important in that it aids to the liberation of our people,” Catlett said.

Catlett desired more than equality, that should be the baseline, the least to expect; she wanted liberation. Liberation, the freedom and empowerment to pursue the highest individual and community aspirations.

While raising a family and teaching in Mexico, Catlett never lost sight of the Black liberation struggle in the United States. As she told Ebony magazine in 1970, “I am inspired by Black people and Mexican people, my two peoples.”

“What I admire most about Elizabeth Catlett is her remarkable clarity both artistically and politically. Catlett saw her politics and her art as inextricable,” Morris said. “That isn’t to say that she didn’t go through a process as a young artist to think through how to accomplish the sophisticated merging of the two, but I would say that from 1946 onward, all the work she had done in D.C., Iowa, Chicago, and New York were a scaffold for her experience in Mexico. Working at the Taller de Gráfica Popular allowed for a clarifying moment of vision, one that drove her work—politically and artistically—for the rest of her life. Very few of us have the grace of that clarity, and Catlett is remarkable for embracing her vision and maintaining it for decades.”

Catlett’s life spanned lynching to Obama. World War I to the War on Terror. The Great Depression and the Great Recession. Her long life, activism, and artwork are impossible to consider without drawing parallels between them and America circa 2025.

Culture Under Attack

Elizabeth Catlett, ‘Homage to My Young Black Sisters,’ 1968 red cedar, overall (without pedestal): 181.6 x 33 x 31.8 cm (71 1/2 x 13 x 12 1/2 in.); pedestal: 57.8 x 58.4 x 58.4 cm (22 3/4 x 23 x 23 in.).

Art Bridges © 2024 Mora-Catlett Family / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

America’s new Red Scare has government, corporate and cultural forces targeting activists speaking out against the Israeli genocide in Gaza, smearing pro-Palestinian protestors as antisemitic. Students are being deported. Artists, their funding and exhibitions pulled. Professors fired.

They understand the “all” Catlett was talking about. “All” implies sacrifice.

Citizenship. Statelessness. Borders. Banishment.

“A Black Revolutionary Artist and All That It Implies” being staged at the National Gallery in Washington, D.C., one mile from the White House, makes it all the more so impossible to divorce from current events. The exhibition has a “see it while you can feel,” before the barbarians get to it.

On March 27, 2025, Donald Trump issued an executive order attempting to bring the Smithsonian Institution to heel. The order seeks to reinforce the political right’s desired white supremacist, patriarchal, colonial story of America. The flag-waving, “we’re #1” version. The story Elizabeth Catlett spent a lifetime combatting.

Anything taking place at the Smithsonian Trump considers “improper, divisive, or anti-American ideology” is in the crosshairs. Can the National Gallery be far behind for highlighting the work of a “Black Revolutionary Artist?’’

Catlett’s defiant Homage to My Young Black Sisters (1968) feels sculpted and installed to confront the Trump administration, although that was not the intent of either.

“In honoring Elizabeth Catlett’s legacy, we hope that her work will resonate as a poignant reminder of art’s power to ignite change and unite communities in the ongoing struggle for equality and liberation,” Dalila Scruggs, Augusta Savage Curator of African American Art at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, said when announcing the exhibition. “A Black revolutionary artist, Catlett made real, material sacrifices—including nine years of political exile—to speak truth to power and to make art for all.”

Cultural workers will soon be put to the decision of making similar “material sacrifices” or bending their knee to tyranny. The White House and its hatchet men attacking culture are coming for the artists, curators, museum directors, docents, writers, and editors who value freedom and liberation and Black history and women’s history and ideas and progress. Jobs will be lost. Careers lost. Imprisonment and deportation possible. Government surveillance.

The “all” Catlett spoke of.

Being a “Black Revolutionary Artist and all that it implies” will be visited upon them. Look to her for strength. Stay true to your principles, come what may. When the world faces darkness, every individual shining light is required for the fight, no matter how seemingly small.

After opening last year at the Brooklyn Museum, following its presentation in Washington, the exhibition travels to the Art Institute of Chicago later in 2025.

More From Forbes