An artist from Cleveland, Ohio is transforming a classic 1947 Greyhound bus, which he saved from a Pennsylvania junkyard, into a traveling museum.

Robert Louis Brandon Edwards, who is also a historian and preservationist, is tearing out the bus’s interior (in a previous life in the 1970s it was a motorhome equipped with a kitchen, bathroom, and bedroom) so he can turn it into the Museum of the Great Migration.

The Great Migration was a period between around 1910 and 1970, when millions of African Americans uprooted from the rural South to the North America’s Midwest, West, and Northeast. The museum will highlight the experiences and hardships they endured as they migrated north, including racism, Jim Crow segregation laws, and violence. Its program will include virtual reality exhibitions.

Related Articles

“Depending on how quickly I can raise the funds to get the bus operational again, I hope to have it on the road by this time next year, and plan to hit all of the major Great Migration destination cities,” Edwards told ARTnews.

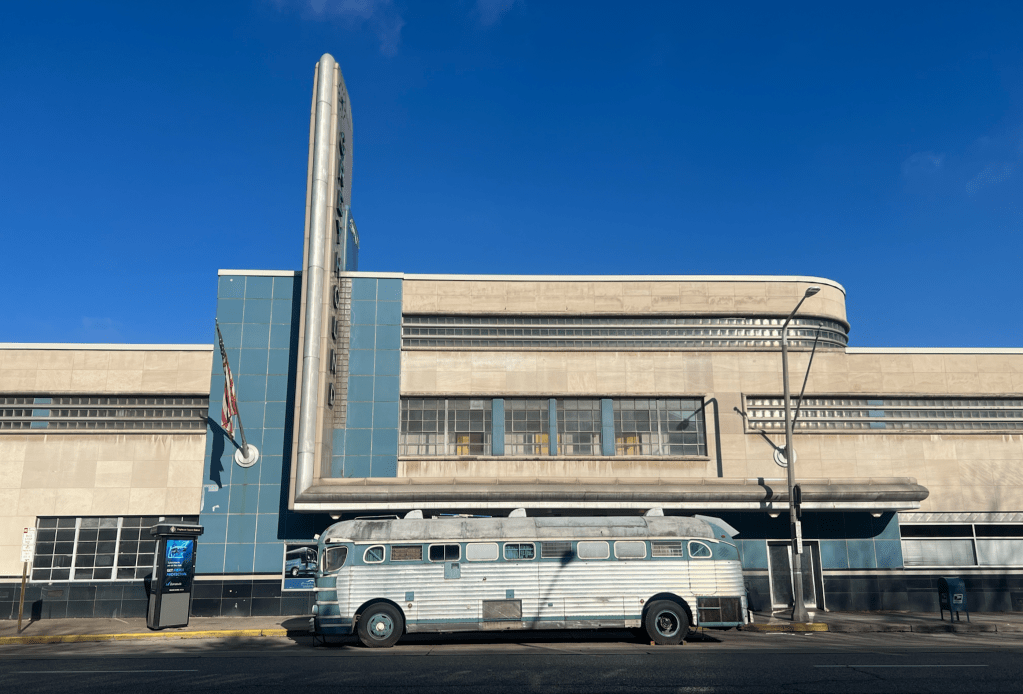

The bus was designed by Raymond Loewy, who also designed a number of the cars featured in The Negro Motorist Green Book, a 1930s-era guidebook for African American road trippers which detailed safe stops. It originally operated out of the Great Lakes region of America, making stops in cities including Chicago, Cleveland, Detroit, New York, and Philadelphia, “all major destinations for Black southerners during the Great Migration,” Edwards said.

The bus is currently parked outside a Greyhound terminal in Cleveland on Chester Avenue. The building was designed in 1948 by architect William Strudwick Arrasmith in the Streamline Moderne, post-Deco style. Later this year, the terminal is permanently closing its doors, as Greyhound services struggle against factors like increased competition from airlines and ride-sharing services. It is slated to be turned into a performance venue by Cleveland-based arts education nonprofit Playhouse Square.

Edwards’ museum project, part of his Columbia University doctoral studies in historic preservation, is in partnership with Playhouse Square. He was inspired to launch it by his grandmother, Ruby Mae Rollins, who travelled on Greyhound buses from Fredericksburg, Virginia to New York with her two daughters, Cindy, and Linda (Edwards’ mother).

“I thought of the stories that my grandmother shared with me and how traveling while Black during the era of Jim Crow was both liberating and challenging,” Edwards told ARTnews. “It made me realize that the car, train, and bus are spaces that need to preserved to expand the field of preservation and expand the archive of spaces that represent the Black experience.”

He continued: “I realized that while some museums interpret the Great Migration, there was no museum entirely dedicated to the Great Migration. The Great Migration brought Southern African Americans to the North, West and Midwest which not only affected industrialism and urbanism, but art, food, music, culture, literature, and television. We’re all products of migration and this bus museum will hopefully bring us together over this commonality.”

Edwards told The Art Newspaper that during the mid-20th century, Black Greyhound passengers were often subjected to harassment and assault. He said they tended to bring their own food for the journeys because there was no guarantee roadside restaurants would let them enter. “They didn’t know which places were safe for them to use,” he said. “Greyhound bus stations, to me, are like Ellis Island.”

In 2022, Edwards said he was compelled by a “crazy idea”: Did any buses used during the Great Migration survive? After some searching, he found one in Pennsylvania listed for $12,000 but managed to haggle the price down to $5,500 in cash. However, shipping the bus to Cleveland on a flatbed truck cost him $7,000. Several components had survived one of the previous owners turning it into a motorhome, including the back bench that Jim Crow laws forced Black passengers to use.

Playhouse Square purchased the Greyhound terminal for $3 million before Edwards asked the nonprofit if he could park the bus outside. Craig Hassall, Playhouse Square’s president and chief executive, told TAN that “the synchronicity is palpable.”

He added that exhibitions at converted terminal could also explore Ohio’s Black history as a result.

“The bus serves as an alternative ‘vehicle’ of inquiry into how regular Black people navigated cultural, social, and physical landscapes,” Edwards told the Cultural Landscape Foundation. “I wanted to understand what my grandmother’s experience may have been like riding on a segregated bus to an unfamiliar city in the North. Was it loud? Was it warm? Was it comfortable? Was it scary? Figuring out what that ‘in-between’ moment traversing the American landscape was like is important to me. I also wanted to challenge and change how we practice and implement research and pedagogical methods in preservation.”