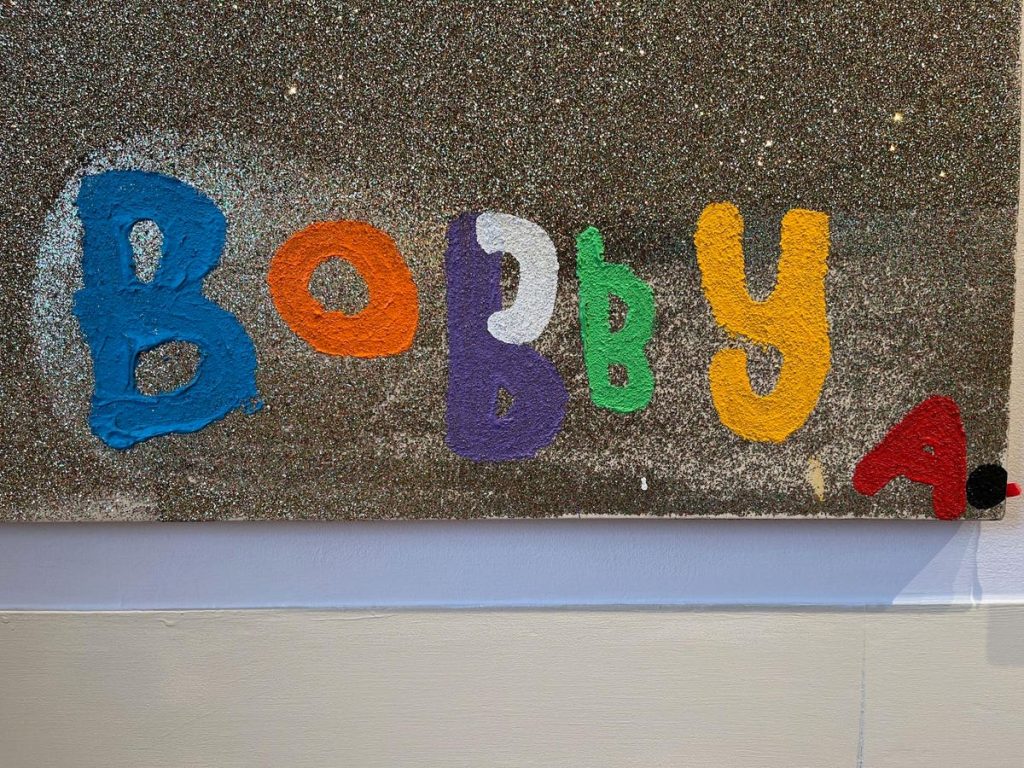

Bobby Anspach signature on one of his paintings installed at the Newport Art Museum.

Chadd Scott

Bobby Anspach (1987–2022) wanted to save the world. Art was the best way he could think of to do it.

Anspach believed he could create a singular sculpture that, once experienced, would transform even the most sadistic, selfish individual into an empathetic person who felt unity with all humanity and a responsibility to protect people and the planet. If he ever got it right.

The evildoers were who Anspach most wanted to reach. His 2017 Master of Art thesis mentions Donald Trump and Elon Musk by name.

“Since Donald Trump was sworn into office this year (2017), it seems unlikely that human life is going to be able to exist on this planet in the way that we have known it, as the result of the climate alone,” Anspach wrote. “My fear, however, is that once it starts to get so bad, people in power are going to make even more rash decisions than they already have.”

Anspach knew the world was in grave peril then. He knew who was to blame. It is in even graver peril today because of the same villains who’ve continued acquiring more power and wealth and greater means and audacity to unleash it upon humanity.

“Right now, a very small percentage of people hold the power to destroy or save this planet,” Anspach said during his life. “They are my target audience.”

Anspach worked desperately on his mind-altering sculpture with the power to turn even the blackest of hearts.

“He made artwork like his life depended on it,” Anspach’s graduate sculpture program professor at the Rhode Island School of Design, Taylor Baldwin, writes in an essay for “Bobby Anspach: Everything is Change,” a survey of Anspach’s life’s work on view June 21 through September 28, 2025, at the Newport Art Museum in Newport, RI.

Anspach, tragically, would not have long to commit to the pursuit. He died in a drowning accident at age 34.

Highlighting the exhibition are two of his experimental sculptures, what Anspach called “Places for Continuous Eye Contact,” room-filling, participatory installations representing as close as he came to his ultimate goal of designing a vessel that could save the world one person, or two people, at a time.

He believed this could be achieved through the power of continuous eye contact.

“Eye contact has always been critical for Bobby,” the artist’s father, Bob Anspach, told Forbes.com. “His eyes are amazing. People always comment about his eyes. One of the reasons they are amazing is because he actually looks at you. One makes oneself vulnerable when one looks at Bobby’s eyes.”

Bobby Anspach believed that vulnerability was the key to unlocking something.

“If we all allow ourselves a special type of freedom, of vulnerability and risk, of connection, that we–and maybe the world–could become forever changed,” Anspach writes.

Freedom.

Freedom was at the core of what Anspach believed could save the world.

Freedom from the self.

“(Bobby) believed that he had experienced a truth through deep meditation and far out thinking–like as far as you could get–and experiment with lots of different states of consciousness,” Baldwin said at a press preview for “Everything is Change.” “He understood something fundamental about consciousness and the lack of separation of self that would essentially convert anyone into a sense of obligation.”

An obligation to save the world. To do good.

“Because he knew that truth, he wanted to make sure he could share it with as many people as possible,” Baldwin explained. “He thought he had seen this truth that he needed to share, and there was a sense of urgency around, ‘It shouldn’t just be me. I need to spread this.’”

What was “the truth” according to Anspach?

His master’s thesis details it, in part:

“Every problem in the world stems from not seeing that everything is changing and from the deluded sense of a self that is created in the holding on to the changing world. It is what produces greed. It is what produces hatred. It is what produces the feelings of being separate from other people. Seeing that the world is changing and allowing it to be how it is does not make someone apathetic or unable to participate in the world. It leads to a deeper understanding of how things are and a better understanding of why others are suffering.”

Resistance to change.

Nostalgia.

An imagined past “greatness,” perhaps?

“Everything is Change.”

Sharing Transcendence

Installation of recreated Bobby Anspach “Places for Continuous Eye Contact” sculpture at Newport Art Museum.

Pernille Loof

Bobby Anspach was an addict; it runs in the family. He suffered from severe bouts of mental illness requiring hospitalization.

It wasn’t easy being Bobby Anspach. Or his parents.

“I have come to believe that those who are closest to the holy are also frequently closest to the demons; that was Bobby,” Bob Anspach said, paraphrasing a quote that has stayed with him. “The demon part of him was he would hear voices.”

Bobby Anspach experimented with hallucinogenic drugs.

“I took mushrooms with my little brother and I looked outside the window and it was the most beautiful thing I’d ever seen, more beautiful than Van Gogh, and it was inside my own brain,” Anspach states in a video playing at the Newport Art Museum as part of the presentation.

That was the mind-altering, life-changing experience Bobby Anspach was trying to recreate in his sculptures, his “Places for Continuous Eye Contact.”

“He was intent on creating something that people frequently refer to as a psychedelic experience without any (psychedelics), just by going into his machines for three-and-a-half minutes,” Bob Anspach said.

Father and son would stay up talking long into the night about the sad condition of the world and the artist’s dreams for correcting it.

“He was convinced that he could make sculptures that had the potential to deliver that experience to a viewer, and that they would leave with a sense of–fundamentally–wholeness with the rest of creation and that that would also generate in them a sense of responsibility towards the world, towards solving things like climate change and nuclear war,” Baldwin said. “He was really a true believer that there was a profound, transcendental experience that can be had, that he had had, and he wanted to build a sculptural experience that could deliver that to any viewer and give them a profound sense of presentness and communion with other people, with the world around them.”

Transcendence, the final goal of Buddhism, a state of being without suffering, desire, or the sense of self.

“In 2008, I got sober to save the world,” Anspach relates in the exhibition video. “Soon after getting sober, I was introduced to meditation. Over the past couple of years, I have had the opportunity to experience the fullness of this human life during a number of long meditation retreats, sometimes lasting up to three months. When the mind settles, everything becomes clear.”

Anspach was describing Buddhism.

“I want to create works of art that have the power to transform our awareness, to inspire humanity to do something about this world which is so desperately calling for a response,” Anspach continues in the video.

Visitors can decide for themselves how close he got.

Both of Anspach’s “Places Continuous Eye Contact” in Newport are meant to be used. His vision wasn’t theoretical. He was actively pursuing the creation of his sculpture, his installation, what others have called a “machine,” that could work on a neurological level to inspire people via continuous eye contact to save the world. He devoutly believed such a thing was possible.

“I’ve never worked with a student who was as clearly focused and driven as Bobby was,” Baldwin said. Baldwin and Anspach conversed almost weekly between 2015 and 2017 when Anspach was in the RISD sculpture program. “When he came into the program, he told me straight up, ‘I’m only trying to make one sculpture and once I make it perfectly, once it works, I won’t need another sculpture.’”

Continuous Eye Contact

The “Places for Continuous Eye Contact” installations at the Newport Art Museum are exact replicas of ones Anspach created, fortified for repeated use by the public and made more accessible and safer. Everyone is welcome to experience.

One is designed for individual use, with participants laying down and staring up into their own eye via mirror. The other is for two people. Preferably strangers. Anspach thought the vulnerability of staring directly into the eyes of strangers led to a more powerful experience.

For the two-person sculpture, both participants enter a pup tent sized dome, every surface of which is covered with multicolored cotton ball sized poms. The pair sit facing each other, nearly touching. The distance between their eyes is roughly three feet. Both participants wear eyepatches over their left eye. This is crucial.

Anspach’s most successful experiments with the transformative power of continuous eye contact revealed that by removing depth perception, by flattening space and the field of vision, a psychedelic experience could more closely be replicated.

The “Places for Continuous Eye Contact” were as much science experiment and invention as artwork.

“He was trying to get down to the exact refined pattern (of poms and lights) that would cause this (transcendent experience) to happen almost neurologically,” Baldwin explains. “He was experimenting with repeating (pom) pattern, with different size poms, with uniform color, randomized color. He was trying every possible variation to see what would cause this.”

In the two-person sculpture, the participating couple cover their heads with helmets, also covered with poms, and are then covered with a heavy bib, obscuring their clothes and shapes. The bib is also pom-covered. Anyone with claustrophobia may want to pass.

Noise canceling headphones playing ambient music are worn throughout the three-minute experience during which multicolored lights playing in sequence create a fantastical ride. All while staring directly into the eye of the stranger sitting opposite.

Without depth perception, with facial features and body outlines obscured, with the one available eye fixed straight ahead, the interior of the space appears to swirl and pulse. The poms become animated. There is no background or foreground.

Museum docents lead participants into and out of the installations. Their role is critical. Anspach worked with a close friend, actor Carson Fox Harvey, on how best to guide the experience. If this were ever to become successful, Anspach wouldn’t be able to lead every experience. Harvey trained Madison Velding-VanDam who trained staff at the Newport Art Museum on how to guide.

Freedom

Installation of recreated Bobby Anspach “Places for Continuous Eye Contact” sculpture at Newport Art Museum.

Pernille Loof

Freedom. The truth. Transcendence. Saving the world.

Bobby Anspach was an optimist.

More optimistic in humanity’s universal desire to want these things than in believing they were possible to achieve through continuous eye contact.

Bobby Anspach was too good, too free, to understand not everyone in the world seeks freedom. Tens of millions desire control. To control and be controlled. To conform. The safety in control when those doing the controlling reflect those being controlled.

He didn’t believe man was irredeemable. The innate, uncorrectable wickedness of men. That evil–true evil–exists in the soul of men. Millions of them. Many occupying the “very small percentage of people (who) hold the power to destroy or save this planet.”

They are unreachable by art. Unreachable by logic. By morality. By humanity. By truth.

They delight in the suffering of others. The “self” is all they know, all they can understand. They can never be divorced from it. Their selfishness. Their ego. Narcists. Sociopaths.

Bobby Anspach was too good a person to think this base depravity in other people couldn’t be changed. He thought everyone could be reached if only he could reach them. Reach them through his art.

He was wrong.

Donald Trump and Elon Musk and their universe of sycophants who worship wickedness can’t be changed by continues eye contact. Art bounces off them like a ball off a wall. Images of children blown to pieces in Gaza bounce off them.

“I (feel)… he got out–in his mind–just in time because what’s happening with the world today is something he raved against, but he knew it was going to happen,” Bob Anspach said.

Bobby Anspach made sure everything he said and did was kept for posterity. Because of that, a tremendous amount of his thinking, in his own voice, exists. The exhibition video shares only fractions. It does share him detailing a dream which eerily, meticulously, premonitions aspects of his death.

“He realizes in the dream he’s going to die, but ‘it’s all ok,’” Bob Anspach explains, recalling the words of his son. “At first it was horrible, but then it was all ok. It was all ok.”

In the exhibition video, Bobby Anspach questions why he didn’t write a detailed account of the dream, “but I didn’t, the next day I just wrote down three words twice: it’s all ok, it’s all ok.”

It’s not.

But it is for Bobby.

“He was the best son,” Bobby Anspach’s mother Jane Anspach told Forbes.com. “He was the best son; through all of this. He was an amazing kid who had an amazing brain and drove me crazy a lot, but it’s the best ride he could give any two parents who have to go on in the world without the child, because it’s so full of love, and him, and this passion, and this intensity. He was the greatest gift.”

His gift to the rest of us was continuous eye contact, and no, it can’t save the world.

It can’t.

But maybe it can save yours.

It’s worth a try.

Side of Bobby Anspach painting on view at Newport Art Museum reading, “It’s Okay. It’s Okay.”

Chadd Scott