Stay informed with free updates

Simply sign up to the Artificial intelligence myFT Digest — delivered directly to your inbox.

The writer is author of ‘Fallen Idols: Twelve Statues That Made History’

Can you be sure that what you’re reading isn’t generated by artificial intelligence? It’s often easy if you read for content — large language models, or LLMs, are famous for advising you to stick toppings to your pizza with glue, advocating eating rocks and insisting that there are only two Rs in the word “strawberry”. But is there also something in the style?

For the last few months, a theory has been circulating on developer forums that one tell-tale sign is a surfeit of em dashes — the longest and proudest dash, the length of a lower-case m, rather than the modest en dash, the length of an n, or the puny hyphen. ChatGPT is apparently so addicted to em dashes that some users claim it’s impossible to prevent it from — sprinkling — them — through — all of its output, as if Emily Dickinson herself is breathlessly circulating your quarterly report.

The simple way to avoid this, of course, is to write your own emails. But what if you do, and your prose is so banal that someone mistakes it for AI anyway? Mortifying. No doubt many editors, judges and academics have already had the experience of reading a manuscript, court submission or essay and thinking: is this AI, or is the person who wrote it just a bit dense?

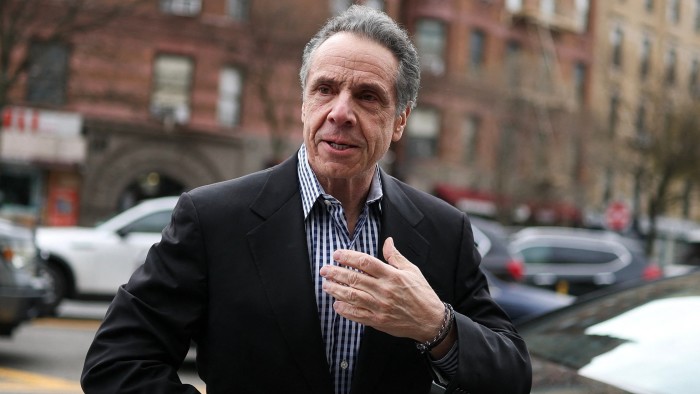

Former New York governor Andrew Cuomo, now running for mayor, released a housing plan last week that was littered with gibberish. It included such passages as: “Nevertheless, several candidates for mayor this year have either called directly for a rent increase or for other measures that would tilt the scale toward lower rent increases. This is a politically convenient posture, but to be in. Victory if landlords — small landlords in particular — are simply unable to maintain their buildings.” Two em dashes in there. Most suspicious. Though, even without those, an attentive reader might have noticed a couple of issues.

A campaign spokesman argued that the plan wasn’t generated by an LLM, saying: “If it was written by ChatGPT, we wouldn’t have had the errors.” How much more embarrassing is it, though, to have typed this guff as a human being? One criticism of AI is that if you can’t be bothered to write your own housing plans, no one else should bother to read them. But what if you did write them, and the problem is you’re incompetent? That’s a real vote-winner.

Some will argue that writing isn’t just the generation of plausible text: it is a process of thinking and analysing. The act of creation is how we challenge and refine our ideas. If you have to work harder to express precisely what you mean, that’s wonderful. The labour of writing expands our brains, understanding, imagination and empathy.

But this point in history is a terrible time to expand our brains. AI is going to take most of our jobs, and in a few years we’ll be serfing it up at the Soylent Green factory. Do you really want to be able to think critically about what you’re doing during your 16-hour shift at the mulcher? Upsetting yourself with intrusive thoughts such as “why have we allowed the world’s worst people to destroy everything worth living for?” and “did Karl Marx have a point?” and “gosh, I hope this stuff really is plankton.” No, you do not.

Much better to reduce your intellectual capacity to that of an obedient drone. A number of studies have already shown that using AI regularly impairs your cognitive function. So by all means keep generating those emails, em dashes and all, and turn your brain into soup.

There may be those among us who are not content to accept this future; who still hope and believe that human craft and creativity, even human life, have meaning. Suckers! What has humanity ever done for shareholder value? Still, if you don’t want your writing to be confused with AI, it’s not really a question of what punctuation you use. Just try to write something worth reading.