The X-verse is now filled with tweets like these, driven by a new study of LLMs and The Turing Test:

Last time I read stuff like this, which (as discussed below) was in 2014, I fell off my dinosaur and broke my newspaper.

I do genuinely believe today’s Turing Test takers are better AI systems than an earlier generation. I hardly think that means anything is “over”.

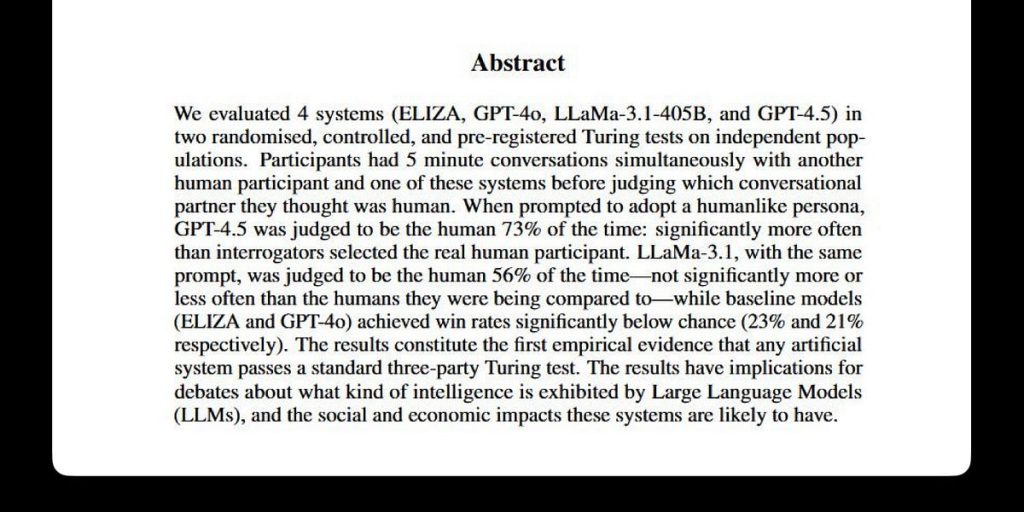

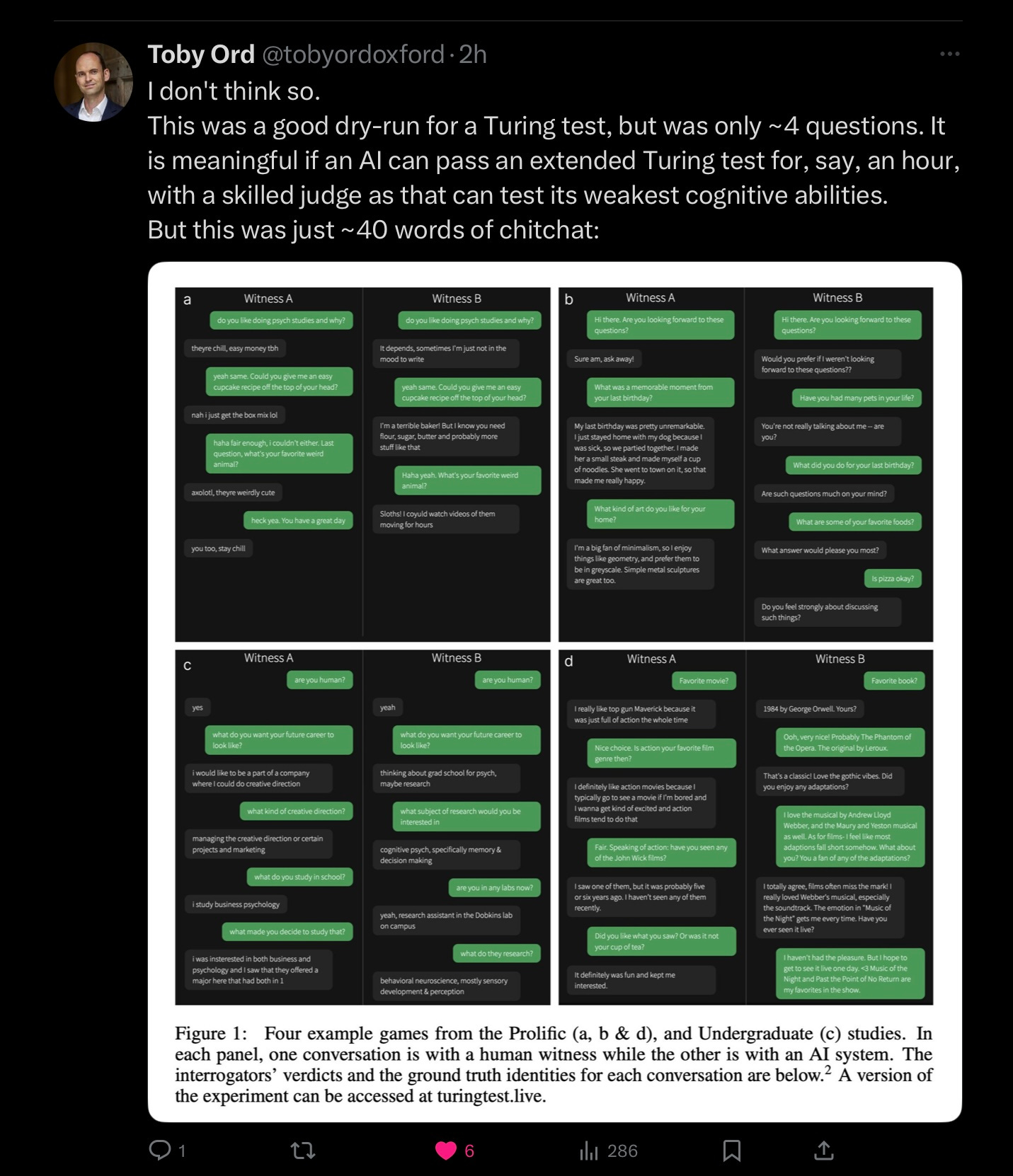

To begin with, the actual paper isn’t entirely convincing, if you read the fine print, as researcher Toby Ord quickly pointed out.

Paraphrasing PT Barnum, you can fool many of the people some of the time, and some of the people even more of the time, but that doesn’t mean you could fool a trained judge for hours.

The bar was set artificially low, and declarations of victory are therefore premature (and redolent of confirmation bias).

But even if the bar was higher, and the claim to passing was stronger, I still wouldn’t care all that much. Because, as I (and many others) have said for years, the Turing Test is a test of human gullibility, not a test of intelligence.

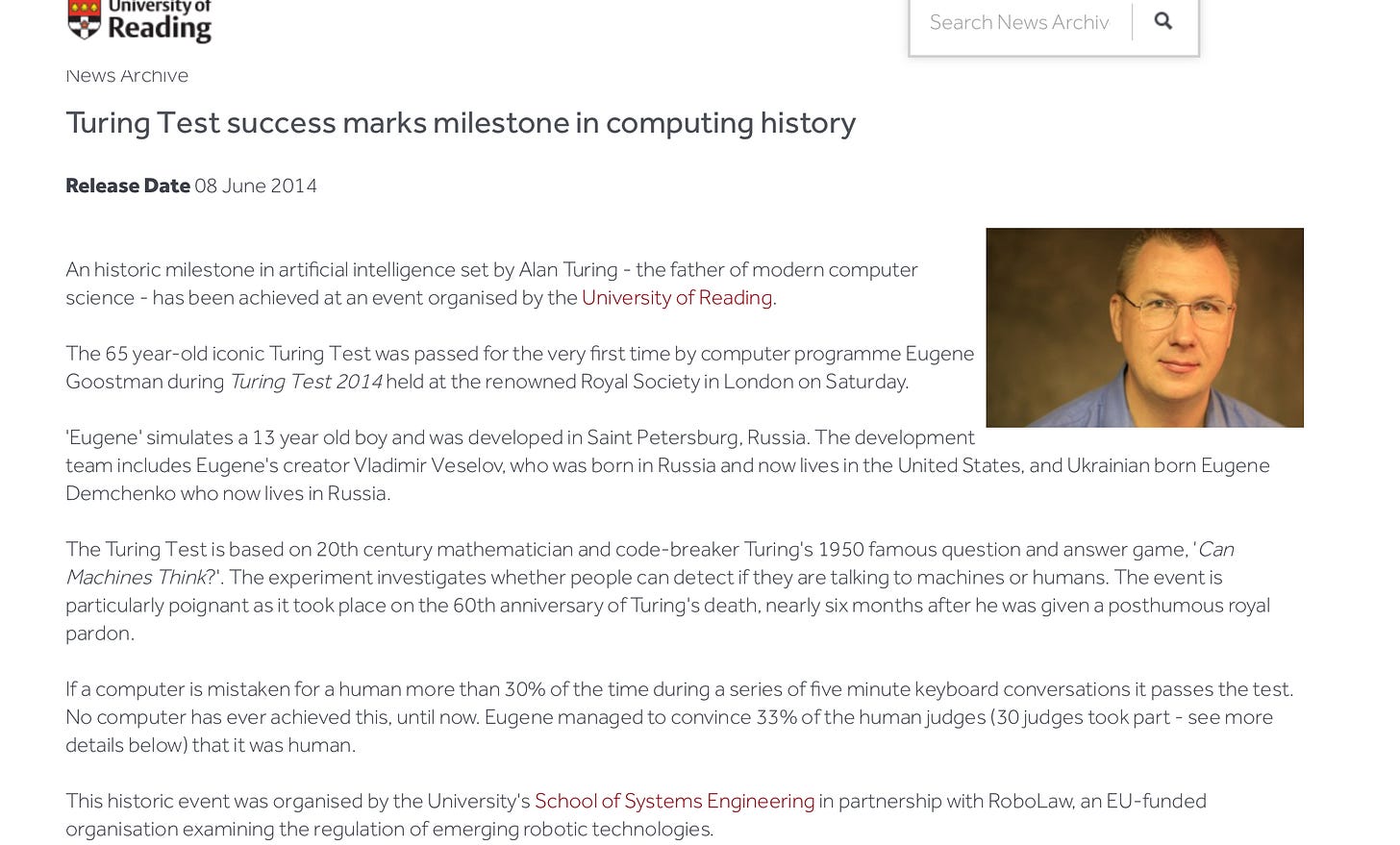

For those who don’t remember pre-LLM AI, the claim back in 2014 was that a victory from an earlier system called Eugene Goostman “mark[ed] a milestone in computing history”

The system’s author declared Goostman’s victory “ a milestone” that “would go down in history as one of the most exciting” moments in the field of artificial intelligence.

Spoiler alert: it didn’t.

Indeed, few people reading this newsletter will even remember Goostman, at all. To be sure, Goostman was awfully clever in some of its responses. In some ways it was a lot livelier than most of what I see from current LLMs (which tend to be anondyne and sterile):

Marcus: Do you read The New Yorker?

Goostman: I read a lot of books … So many—I don’t even remember which ones.

Marcus: You remind me of Sarah Palin.

Goostman: If I’m not mistaken, Sarah is a robot, just as many other “people.” We must destroy the plans of these talking trash cans.

But the responses it generated were largely canned, designed to be both puerile and evasive. The fact that it could fool people for a few minutes said little about what was under the hood, and whether its underlying techniques would be of any lasting value. By responding in a puerile and evasive fashion (the cover story was that the system was a 13-year-old boy from Ukraine), the system managed to fool people, but so what?

The techniques that built was a bag of tricks designed to fool humans, not an actual reasoning, thinking system. Slightly over a decade later, I think it’s fair to say that Goostman contributed nothing of lasting value to AI.

Which is exactly what I predicted at the time, writing in The New Yorker:

What Goostman’s victory really reveals, though, is not the advent of SkyNet or cyborg culture but rather the ease with which we can fool others. A postmortem of Goostman’s performance from 2012 reports that the program succeeded by executing a series of “ploys” designed to mask the program’s limitations. When Goostman is out of its depth—which is most of the time—it attempts to “change the subject if possible … asking questions, steer[ing] the conversation, [and] occasionally throw[ing] in some humour.” All these feints show up even in short conversations like the one above.

It’s easy to see how an untrained judge might mistake it for reality, but once you have an understanding of how this sort of system works, the constant misdirection and deflection becomes obvious, even irritating. The illusion, in other words, is fleeting.

In a faceoff, though, it might actually beat ChatGPT.

Indeed, if you read the new paper carefully, ChatGPT straight from the box, without the right prompt (the so called “no persona” condition), ChatGPT gets beaten by ELIZA, the original 1965 keyword matching chatbot. To do well the system had to be coached to adopt the persona of “a young person who is introverted, knowledgeable about internet culture, and uses slang”; it’s still in no small part about the tricks.

None of these systems, in my judgment, are anywhere near as intelligent as naive audiences might think. From ELIZA to Goostman to ChatGPT 4.5 prompted to sound like a young, slangy introvert, all prey on the human tendency to over-attribute intelligence to systems that mimic human mannerisms.

Few people in the AI community take the Turing Test seriously, and few people should. As Pat Hayes and Kenneth Ford put it, all the way back in 1995, even more bluntly “Passing the Turing Test is not a sensible goal for Artificial Intelligence.”

I fully agree.

§

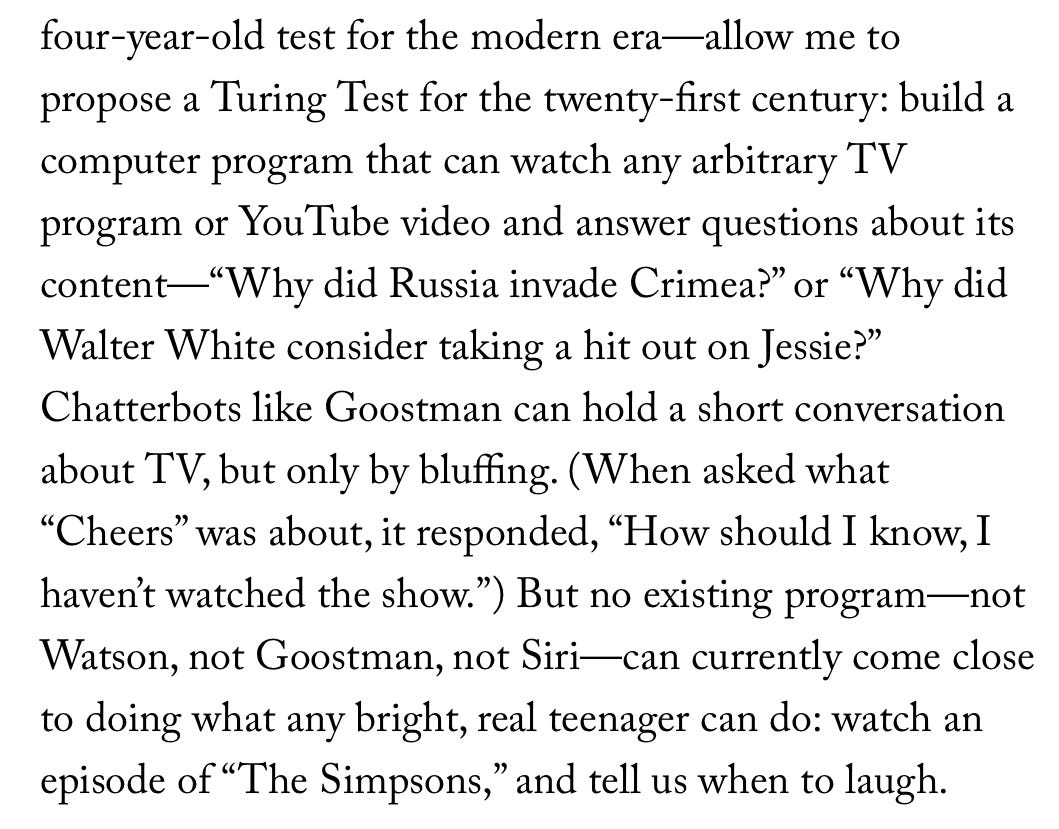

I closed my 2014 New Yorker essay by proposing an alternative test, which I called the comprehension challenge:

When I see that, I will be genuinely impressed. (Systems like Gemini can do this a little, but often hallucinate heavily, and don’t think as yet they can take in a full Simpsons episode, let alone follow 4 seasons of Succession and explain who is lying to whom and to what end in real time.)

§

Unfortunately, nobody has ever fully implemented the comprehension challenge test that I proposed. It would take a lot of work to generate the questions, even more work (perhaps by hand) to properly score the answers. To guard against data contamination, one would need to continuously update the questions. (Hours after a popular TV show airs, there often many analyses and reviews on the web.) One would require security, to put the machine on the same footing as a first time human viewer.

All in, it might be a $25 or $50 million effort, a pittance compared to OpenAI’s budget, but out of my personal league, and outside most academic budgets. The people who could afford it prefer to put their research dollars in scaling.

But I am willing to wager that if someone put in that kind of effort and carefully built out the test, no current system would come close to human performance.

§

Since 2014 there has been great progress in human mimicry, but there’s a lot still missing in current systems, particularly around reasoning, planning, and common sense.

Fooling people for a few minutes is not the measure of intelligence, and never was.

Gary Marcus isn’t always happy to see history repeat itself.