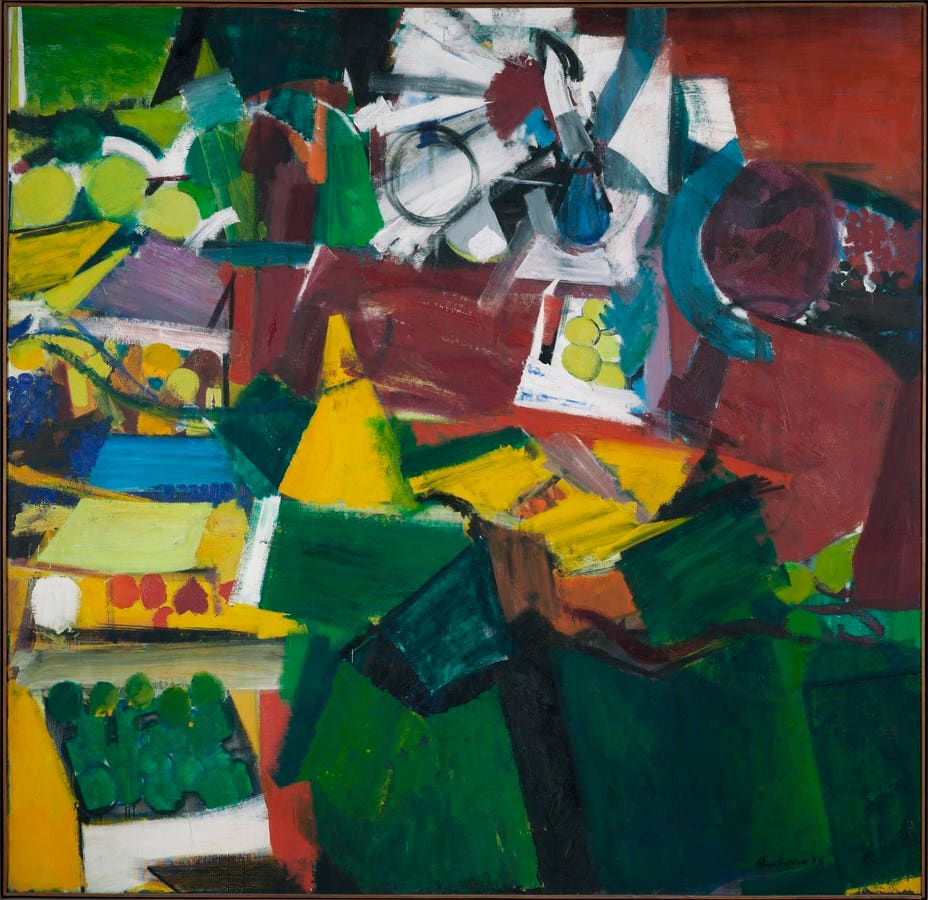

Grace Hartigan, ‘East Side Sunday,’ 1956, oil on canvas, 80 × 82 in., Brooklyn Museum, Gift of James I. Merrill, 1957, 56.180.

© Estate of Grace Hartigan

In the late 1940’s, North Carolina had a novel idea. To begin a state art collection. For the people. To be displayed in a state art museum in the state capital of Raleigh.

No state in the nation had such a thing.

A radical notion for place that at the time thought it was such a bad idea for Black and white people to eat together that it was illegal.

Word of the idea spread. All the way to New York, newly minted as the capital of the Western contemporary art world following the tumult in Paris and mass exodus of artists out of Europe during World War II.

New York gallerist John Myers caught wind of the idea. The gallery he co-owned was unusual in that it was a place for both artists and poets to show and discuss their work. And collaborate.

One such poet was future Pulitzer Prize winner James Merrill. Merrill was raised in absurd wealth as the son of Charles E. Merrill, co-founder of investment brokerage firm Merrill Lynch. The poet Merrill was working with Myers’ gallery to help fund purchases of work by the gallery’s roster of artists for placement into museum collections.

One of those artists was Grace Hartigan (1922–2008). One of those museums was the North Carolina Museum of Art. This story inspires “Grace Hartigan: The Gift of Attention,” the largest exhibition of Hartigan’s work in over two decades, on view through August 10, 2025, at the museum.

Jared Ledesma is the Curator of 20th-Century Art and Contemporary Art at the North Carolina Museum of Art. Interested in the museum’s connection to Hartigan, he began researching. He found a letter from Myers to Merrill where the gallerist relayed what was taking place in Raleigh with the new state museum and how the institution’s associate director, James Byrnes, was especially keen on acquiring contemporary art. Another progressive notion for the era, particularly in the South.

The gallery sent Hartigan to Raleigh to sit on a panel of jurors and judge the first contemporary art exhibition held there. This was near the peak of the Abstract Expressionist movement. The movement of Pollock and Krasner and Rothko and the de Kooning’s and Hartigan and Mitchell. The movement that set New York and American painters atop the mainstream contemporary art world. Made them superstars. The first explicitly original mainstream, contemporary, American art movement in the eyes of many.

Merrill funded an acquisition of Hartigan’s work for the North Carolina Museum of Art, along with the Brooklyn Museum, the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, the Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh, and others.

The connection between Hartigan and Merrill, between painter and poet, sent Ledesma down a rabbit hole.

“I was aware of past exhibitions focusing on the painters and poets of the New York School, but I didn’t find much focusing on Hartigan herself,” he told Forbes.com. “A lot has been written on Frank O’Hara and how the painters were, in some ways, his muse, but I really wanted to bring Hartigan to the fore after finding so much work that she created that’s really indebted to the poets in many ways.”

The NCMA exhibition centers Hartigan’s engagement with New York’s contemporary poets during the 50’s and 60’s, arguably the pinnacle of her career, the period from which the artworks in the show are drawn.

Hartigan created artworks in direct response to poems. Her Oranges paintings. There’s a painting in the Raleigh exhibition called Snow Angel, so named a Barbara Guest poem. Merrill, a poet, of course, was a major patron. As were other poets who helped support Hartigan through the purchase of paintings.

“Daisy Alden, the poet, she bought two works by Hartigan. One was a portrait of her and her lover, Olga,” Ledesma explained. “The poets also wrote art criticism. This was also a boost for Hartigan. She was a subject of a few reviews written in ‘ARTnews’ by Frank O’Hara and James Schuyler, another thread in direct connection.”

AbEx-ish

“Grace Hartigan: The Gift of Attention,” installation view at the North Carolina Museum of Art.

North Carolina Museum of Art

Hartigan is generally associated with the Abstract Expressionist movement. Unlike her Ninth Street female peers Helen Frankenthaler, Elaine de Kooning, Lee Krasner, or Joan Mitchell, however, Hartigan has not had a major show in recent years.

The AbEx categorization in Hartigan’s case is an oversimplification. Through 40 works, the NCMA exhibition reveals how she channeled both abstraction and figuration to create something uniquely her own.

“It relates to possibly why there hasn’t been a large focus on Hartigan, I think ultimately, it’s because it’s hard to classify her work into one camp. The work is at one point abstract, and then another, very figurative, and then it also, at some points, falls in between,” Ledesma explains. “That was her goal. She never wanted to be within one certain category. She goes back and forth between both styles, very rebelliously, I would add. She definitely embraced the all-over democratic style that she learned from Pollock firsthand, from seeing his cavasses, but then also the insertion of the figure from watching Willem de Kooning and his Women works, except her figures are just a bit more concrete and formed. She lives in between.”

The show Hartigan visited Raleigh to judge in the 50’s featured an amazing roster of artists including herself, Frankenthaler, Louise Bourgeois and Mary Abbott.

Mary Abbott

“Mary Abbott: To Draw Imagination” installation view at Schoelkopf Gallery New York.

Schoelkopf Gallery

Abstract Expressionism is inseparable from New York, and for AbEx in the Big Apple, visit Schoelkopf Gallery where “Mary Abbott: To Draw Imagination,” the first comprehensive survey of Abbott’s (1921–2019) career, can be seen through June 28, 2025. The retrospective presents more than 60 works spanning from 1940 to 2002.

Highlighted are Abbott’s bold explorations of color, form, and media, tracing her evolution from early figurative works and Surrealist influences to her later large-scale Abstract Expressionist paintings. It will also bring to light Abbott’s role as one of the few women artists deeply engaged in The Club, a members-only artists group dedicated to shaping the Abstract Expressionist movement.

Born and raised on New York’s Upper East Side, Abbott studied with George Grosz, Rothko, Barnett Newman and Robert Motherwell, and maintained deep artistic connections with André Breton, Hartigan, Pollock, O’Hara, and the de Kooning’s.

This retrospective presents rarely seen works from the Estate of Mary Abbott, among them, Abstract Expressionist canvases (1950s–60s) created in dialogue with Pollock, Willem de Kooning, and Joan Mitchell, highlighting her synthesis of action painting and automatic drawing techniques.

Alongside Elaine de Kooning and Mitchell, Abbott was one of few women invited to join The Club, a group of artists dedicated to shaping Abstract Expressionism. Her work pushed the boundaries of the Abstract Expressionist movement and painting itself, incorporating diverse materials and tools, such as oil, oil stick, charcoal, pastel, collage, and paw and handprints.

Mildred Thompson

Installation view, ‘Mildred Thompson: Frequencies’ at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami, May 10 – October 12, 2025. Photo: Oriol Tarridas.

Courtesy the Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami.

Abstract Expressionism was one aspect of Mildred Thompson’s (1936–2003) creative output. That came later in a four decade career also featuring a most unusual period of reliefs, assemblages, and collages made out of wood. Examples of all can be found at “Mildred Thompson: Frequencies” on view at the ICA Miami through October 12, 2025.

The most comprehensive solo museum exhibition to date for the artist, approximately 50 works from 1959 to 1999–paintings, sculptures, etchings, drawings, assemblages, and musical compositions–are brought together.

Thompson’s AbEx-leaning paintings and works on paper dazzle. They are characterized by energetic mark-making, a profound understanding of color, and complex, absorbing compositions. She was interested in physics and astronomy and through her own interpretation, sought to visually represent scientific theories and systems invisible to the eye.

Often featuring radiating swirls of color and gesture, her showstopping paintings from the 1990s delve into the invisible forces of particle physics and quantum mechanics (String Theory, 1999) and magnetic fields (Magnetic Fields, 1991). In her “Radiation Explorations” series (1994), she translated radiation and UV light into luminous colors and gestural brushstrokes. Later in her career, Thompson focused on cosmologies and astrological phenomena. For the first time in over three decades, a significant selection of her “Heliocentric Series” (c. 1990–94) will be on display.

These works are presented alongside her largest paintings, the series “Music of the Spheres” (1996). Depicting Mercury, Venus, Jupiter, and Mars, each of the four paintings is accompanied by an original electronic music composition by Thompson. The tracks, collectively titled Cosmos Calling, evoke science fiction soundtracks and Afrofuturist music. Thompson described them as “a journey through the soundscape of space inspired by the NASA Voyager recordings.”

More From Forbes