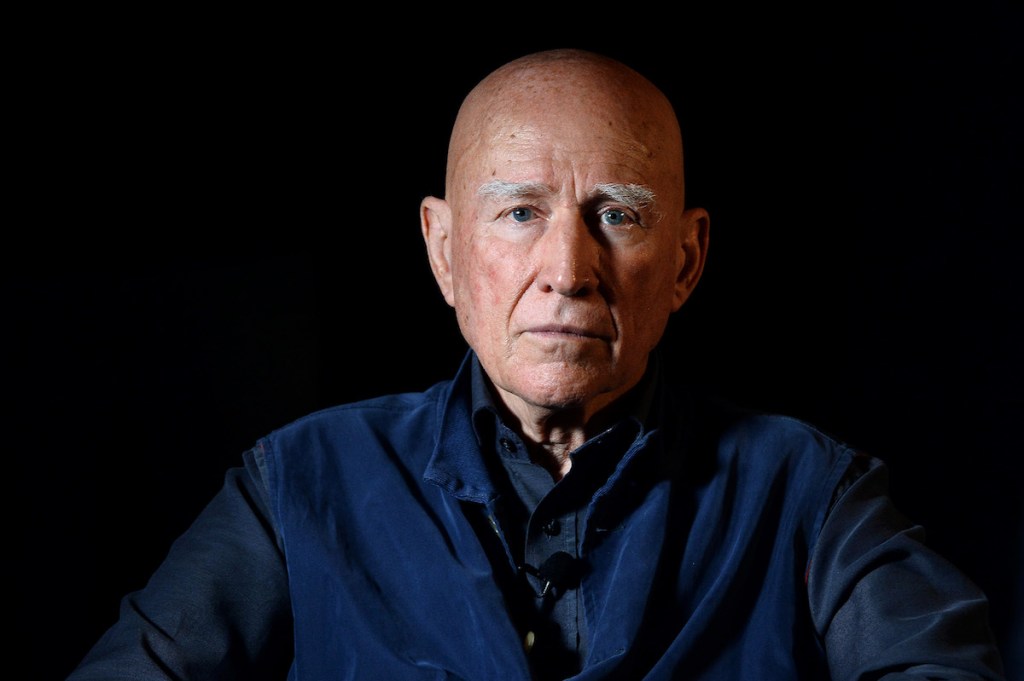

Sebastiao Salgado, a photographer whose memorable images of worker exploitation, environmental destruction, and human rights abuses gained him widespread acclaim, has died at 81.

His death was announced on Friday by Instituto Terra, the organization he cofounded with his wife Lélia Wanick Salgado. The New York Times reported that he had health issues since contracting malaria in the 1990s.

Salgado was considered one of the most beloved photographers working today. His lush black-and-white pictures were taken in seemingly every corner of the world, from the Sahel desert to the Amazonian rainforest to the farthest reaches of the Arctic. In bringing his camera to places many hear about but rarely see, Salgado provided the world with irrefutable glimpses of all the horrors man had unleashed upon the earth.

Related Articles

He worked within a lengthy tradition of documentary photography, using his images to tell the truth about the sights he observed. But whereas many documentary photographers and photojournalists purport to retain objectivity, Salgado got close to his subjects, holding lengthy conversations with the people who passed before his lens and waiting for long periods to get the right shot.

“What sets Salgado’s images apart from this work is his engaged relation to his subject, a product of his life-long commitment to social justice,” wrote critic David Levi-Strauss in Artforum. “The emotional static that allows us to turn away from other photographs of starving people, for instance—their exploitativeness, their crudity, their sentimentality—is not there to protect us in the case of Salgado’s reportage.”

His photographs have been published widely in the media and have been the subject of countless photobooks. Unusually, for a someone who could be labeled a photojournalist, Salgado was also accepted in the art world, with the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art organizing his first retrospective in 1991.

Not all critics praised Salgado, who was repeatedly accused of exploiting his subjects. Those allegations even resurfaced last year when Salgado’s “Amazônia” photographs, featuring shots of Indigenous Amazonians, appeared in Barcelona. The Guardian quoted João Paulo Barreto, a Yé’pá Mahsã anthropologist, who recalled walking out of the show: “For me, it feels such a violent depiction of Indigenous bodies. I mean, would Europeans ever deign to exhibit the bodies of their mothers, of their children in this way?”

Even Salgado’s fans tended to eye his photography with suspicion. Weston Naef, then a curator at the Getty Center, told the New York Times Magazine in 1991, “For myself, one problem is the nagging question of whether Salgado is not sometimes exploiting his subjects rather than helping his subjects.”

Salgado seemed to know, however, that his images could not be divorced from him. “You photograph with all your ideology,” he once said. And he frequently directed the money gained from his pictures’ sales toward the communities photographed. The 1991 New York Times Magazine piece said he had recently used those funds to bankroll an artificial-limb factory in Cambodia.

His breakthrough was his 1984 book Autres Ameriques (Other Americas), which was devoted to peasants in Latin America. The series, begun in 1977, was his first done in South America since he fled his native Brazil for Paris amid the thread of the country’s military government, and it was meant to showcase the region’s impoverished communities and their plight.

“The seven years spent making these images were like a trip seven centuries back in time to observe, unrolling before me … all the flow of different cultures, so similar in their beliefs, losses and sufferings,” he told the Independent in 2015. “I decided to dive into the most concrete of unrealities in this Latin America, so mysterious and suffering, so heroic and noble.”

That series, along with a follow-up one devoted to victims of a famine in Africa’s Sahel desert, gained him a loyal following in Europe. Americans seemed to have a tougher time with these photos. Salgado recalled that American aid groups wouldn’t publish the Sahel photos in the US, even though thousands of copies of books with them had already sold abroad. By the ’90s, many Americans knew him only because of one of his very few breaking news pictures: a shot of the the 1981 assassination attempt on Ronald Reagan by John W. Hinckley Jr.

Sebastiao Salgado was born on February 8, 1944, in Aimorés, a small town in Brazil’s Minas Gerais state. His father, a cattle herder, wanted Salgado to become a lawyer, and Salgado initially set out to fulfill his wishes. But when he ended up attending São Paulo University, Salgado instead studied economics. He went on to work for Brazil’s Ministry of Finance.

He married his wife, Lelia Wanick Salgado, in 1967. With the country’s military government on the ascent, Salgado, an avowed leftist, left with his wife and their two children in 1969. They relocated to Paris, where Salgado took courses on agricultural economics at the Université de Paris. He later worked for the International Coffee Organization in London.

His work took him around the world, and with him came his Pentax camera. A 1971 trip to Africa convinced him that photography was “the way to go inside reality.”

While he periodically published his early photographs in magazines, he did not gain greater notice until the 1980s. The publication of Autres Ameriques saw his following grow immensely, and further praise followed for his pictures of workers at the Serra Pelada gold mine in Brazil.

In the new millennium, Salgado’s work became increasingly concerned with climate change and ecological disturbance. His series “Genesis” (2004–11) featured gorgeous shots of glaciers, mountain ranges, and people in arid landscapes.

“There are places where no one from Western civilization has gone; there are humans who still live like we lived fifty thousand years before,” Salgado told Aperture. “There are a lot of groups that never made any contact with anyone else. They are the same as us. There is still a percentage of the planet that is in the state of genesis.” Later, he would say that through the series, he was “transformed into an environmentalist.”

Salgado’s work was collected widely, by institutions ranging from the Museum of Modern Art to Tate Modern. And he racked up plenty of accolades beyond the art world: he was a UNICEF Goodwill Ambassador, and he received countless support for his work done in support of the environment, including for the forest restoration work in Brazil that he did with his wife.

He seemed unconcerned whether he would be memorialized. Speaking to Al-Monitor last year, he dismissed the notion that he was an artist, saying instead that he was a “photographer,” and mentioned that his pictures should be his legacy. “I have no concerns or pretensions about how I will be remembered,” he said. “Photos are my life, nothing else.”