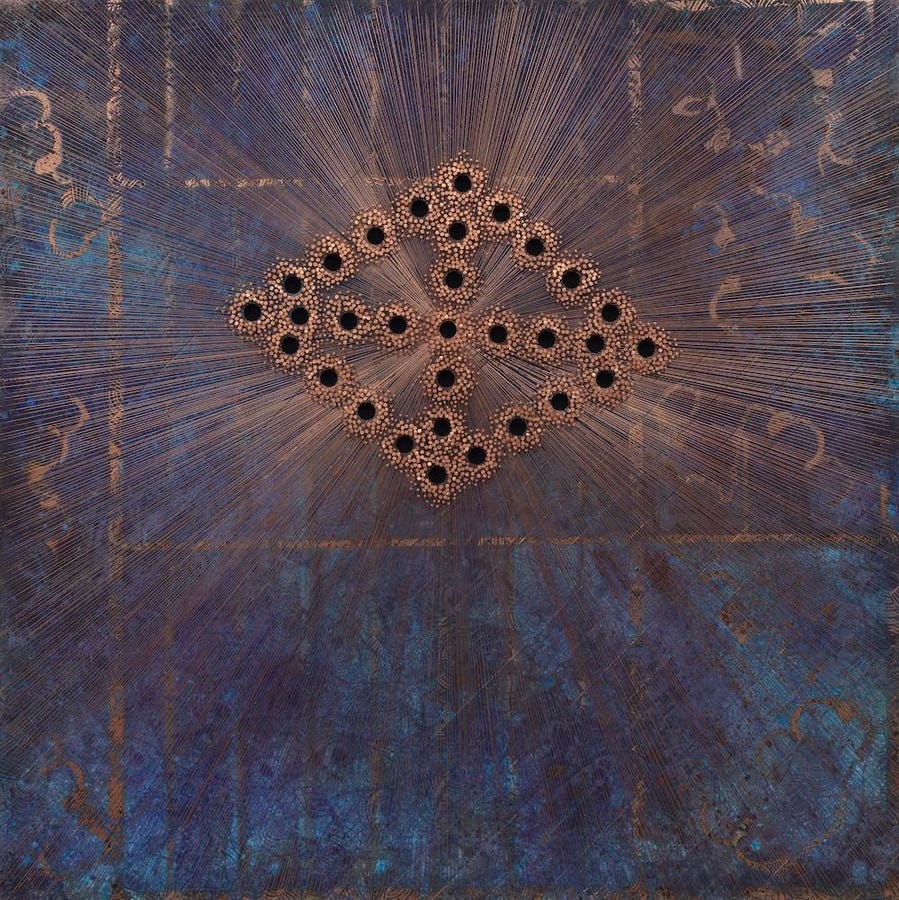

Nari Ward, “Breathing Bars Diagonal Left,” 2020, oak wood, copper sheet, copper nails, darkening … More

Photo: Daniel Kukla. Courtesy Art Bridges.

The First African Baptist Church in Savannah — which was founded by enslaved people and is the oldest continually open black church in North America — has many unique features. Among them, original gas lighting fixtures from when the sanctuary was completed in 1859, pews carved with ancient Semitic languages including Cursive Hebrew and Ethiopian Amharic Ge’ez, and floorboards drilled with holes that form a triangular pattern.

These floorboards were of particular interest to the artist Nari Ward, who first saw them while visiting Savannah to prepare for a solo exhibition at the Savannah College of Art and Design in 2015. There are theories for why the holes exist in the otherwise smooth floor. Many surmise that they represent the Kongo Cosmogram, a religious symbol that portrays the relationship between human and spiritual worlds and has been used for many centuries by the Bakongo people, who live in what is now known as the Democratic Republic of Congo. Others say that the holes were drilled into the floor to allow escaped slaves to breathe. The church may very well have served as a hiding place in the Underground Railroad, given that March Haynes, a deacon of the church, was a known member of the network.

In “Breathing Bars Diagonal Left” (2020), Ward took the shape of these holes, and made them radiant. On a crepuscular blue background covered with faintly gilded symbols of hand cuffs and prison bars, the Cosmogram explodes with beams of light, which in the artwork are represented by thin gold lines. Each hole, which embodies a place where someone might have drawn a breath, is surrounded by golden nails, which cluster like worker bees. Or the spirits of ancestors. One gets the physical sensation, looking at the artwork, that you are witnessing life itself. Oxygen inhaled; carbon dioxide exhaled. Exuberance, miracles. Hope stubbornly clinging on in a dark hiding place, and despite it all, exploding outward with exuberance. In times like these, I looked at the artwork, and started crying.

An installation view of “In Reflection: Contemporary Art and Ourselves,” an ongoing exhibition at … More

Photograph by Stephen Harmon

The artwork is installed as part of “In Reflection: Contemporary Art and Ourselves,” an ongoing exhibition at the Jepson Center in Savannah that showcase the museum’s modest but mighty contemporary art collection, which includes works by Kara Walker, Elaine de Kooning, Chul Hyun Ahn and Rocío Rodríguez. “One of the best parts about working in a museum is continually looking at these cutting edge artists, and what they are saying about the current moment and the times we are living in,” says Erin Dunn, the curator of modern and contemporary art at the museum, who also organized the exhibition.

The Ward piece, however, is on loan from Alice Walton’s Art Bridges Foundation, which aims to provide financial and strategic support to museums across the United States, in part by lending out pieces from its permanent collection upon request. Such as the Nari Ward piece lent to the Jepson Center for a year. “Our goal is getting art out of storage and into museums,” says Ashley Holland, the curator and director of curatorial initiatives at Art Bridges Foundation.

As the curator at a small museum in a city of just under 150,000 people, Dunn works with a modest budget which does not always support the acquisition of works by notable contemporary artists. She was grateful, therefore, to see one of Ward’s works on Art Bridges Foundation’s website. She applied for a loan, and it was granted by Holland and her team. Dunn notes that the loan came with very few stipulations, and that the foundation even paid for shipping. Art Bridges Foundation also loaned “Black Girl on a Skateboard Going Where She’s Got to Go to Do What She’s Got to Do and It Might Not Have Anything to Do With You, Ever” (2022), a ceramic sculpture by Vanessa German, to the Jepson Center for the exhibition.

“We really expect all of our partner organizations to also be doing learning and engagement,” says Holland, noting that she was thrilled to lend the artworks by Ward and German to the Jepson Center. “There were so many local connections,” says Holland. “Both pieces were a great fit for them.”

An installation shot from “In Reflections.”

Photograph by Stephen Harmon

The presence of philanthropy from billionaires was visible throughout the show, which was marked by artwork that refused to cower, including “Black Cotton Flag Made in Georgia” (2018), a 27-foot tall draped American flag rendered entirely in black, and collapsed against a flagpole, by Paul Stephen Benjamin. There were the two pieces from Art Bridges Collection, which is funded by Walton, the richest woman in the world. And then, there was signage leading visitors to Bloomberg Connects, a digital guide to the exhibition funded by Bloomberg Philanthropies. At a time when arts organizations are facing budget cuts — President Trump started eliminating grants funded by the National Endowment for the Arts in early May — these programs from wealthy philanthropists are lifelines for small museums like the Jepson Center.

Dunn, for one, is honored to have the piece by Ward, even if it’s not in the museum forever. Already, a few weeks after opening, school children have visited. They’ve seen the breathing holes, and they’ve felt the life emanating from them. “I think it’s so cool for them to realize that artists come here to Savannah and when they leave, take ideas with them,” Dunn says. “It helps them understand that our small community actually has a really outsized influence on our world.”