Credit: YouTube/Dwarkesh Clips

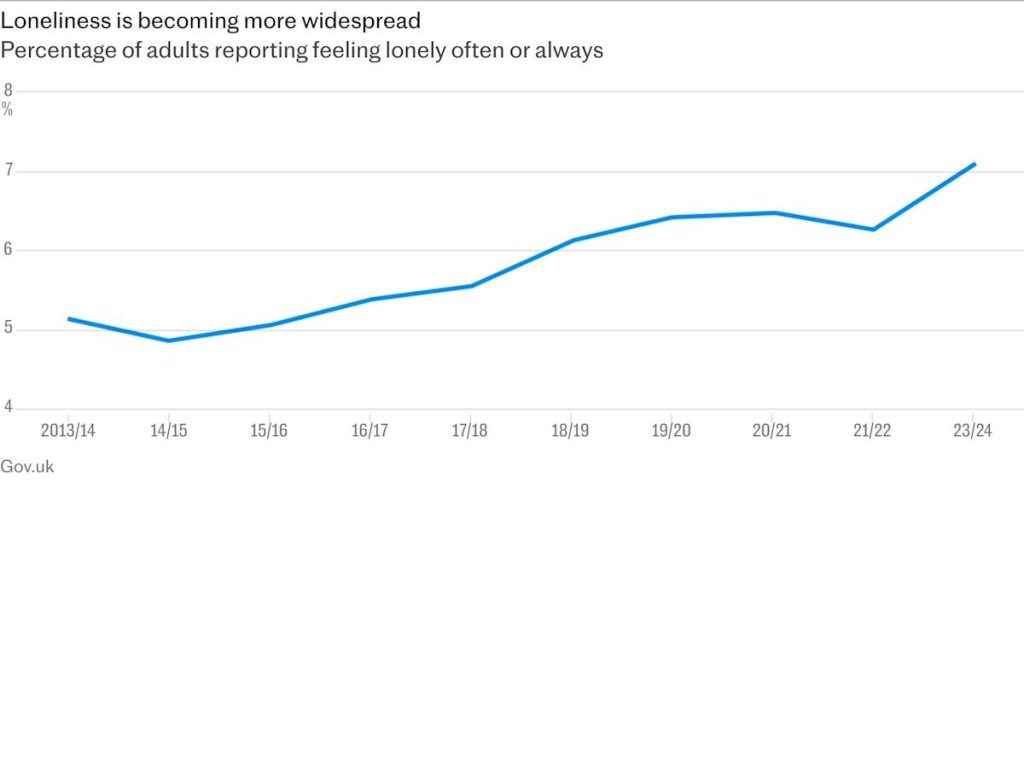

We have never been more connected – yet people are feeling more and more isolated.

Two decades after Facebook began linking us with friends, family and people we’d like to get to know online, loneliness rates are rising.

In the UK, 7pc of people report often feeling lonely – up from 5pc a decade ago. The figure climbs to 10pc among 16 to 24-year-olds who are now spending up to six hours per day online, according to Ofcom data. The UK average is four hours and 20 minutes.

The ubiquity of social media has been blamed for exacerbating feelings of isolation. Meet-ups with friends have been replaced by video calls, group chats and TikTok videos.

In the US, the American Psychological Association found that 41pc of teenagers with the highest social media use described their mental health as very poor.

According to a 2017 study by the University of Pittsburgh, 19 to 32-year-olds who spent the most time on social media felt twice as isolated as those who spent less than two hours a day on it.

Mark Zuckerberg, Facebook’s architect, knows there is a problem.

0805 Loneliness chart

“The average American has fewer than three friends,” the billionaire told a podcast last week. They want “meaningfully more”, he added.

“The average person wants a lot more connectivity than they have. They feel more alone a lot of the time than they would like.”

The tech billionaire’s solution is not to log-off, however. Instead, he wants people to find comfort in machines.

“I think people are going to use AI for a lot of these social tasks,” he told Dwarkesh Patel’s podcast, describing how people could soon enjoy an “always on video chat” with an AI avatar.

“As the AI starts to get to know you better and better, I think that is going to be really compelling.”

While it may sound like science-fiction – recall Joaquin Phoenix falling in love with his AI voice assistant in the 2013 film Her – many are already taking Zuckerberg’s advice.

In the 2013 film Her, Joaquin Phoenix’s character fell in love with his AI voice assistant – Cinematic/Alamy

Millions of teenagers are using MyAI, a chatbot from Snapchat. Character.AI has more than 20m monthly users. The start-up Replika AI, meanwhile, explicitly bills its chatbot as an “AI companion who cares”, one that is “always here to listen and talk, always on your side”.

Zuckerberg has suggested chatbots like these could be useful for “talking through difficult conversations”, and while there is “stigma” around the idea of an AI girlfriend or therapist, soon these could be seen as “valuable … rational … adding value to their lives”.

Yet not everyone believes more technology is really the answer to the loneliness epidemic.

“If you are feeling lonely and lacking a genuine sense of social connection with another person then it is difficult to see how a chatbot can fulfil that need,” says Sam Roberts, a senior lecturer in psychology at Liverpool John Moores University.

Harry Farmer, a researcher at the Ada Lovelace Institute, says AI companions have been designed to “keep you using them for as long as possible” to help make money for the companies behind them.

Tech giants have made them “too agreeable”, he adds, with none of the “friction and awkwardness” of real conversations.

“There is a real concern that, as a result, these systems may make it harder for people to make and keep friends, by leading people to cultivate unrealistic expectations of human relationships.”

The “mission statement” of Meta, Zuckerberg’s tech empire, is to “build the future of human connection”. Until recently, that meant connecting people to their friends and family online (and selling a few billion of dollars of digital adverts in the process).

But now, Zuckerberg appears to be ditching that vision altogether.

Meta has already launched a new AI chatbot app, called Meta AI, and similar bots that can hold a conversation in WhatsApp and Instagram. In the US, users can also hold spoken conversations with their Meta AI bot. They can also create and share customised AI avatars across Meta apps through its AI Studio product.

Zuckerberg said last week he thinks AI friends will “probably” not replace “in-person connections or real life connections” entirely, but that most people could soon be sharing their head-space and social feeds with AI chatbots instead of, or at least alongside, their friends.

It is not clear if the public is on board with Zuckerberg’s vision. A survey from YouGov found that just 10pc of people felt an AI chatbot would give good relationship or mental health advice. Only 17pc felt it would be a good conversation partner.

There is some evidence to suggest AI can help people’s mental health. A study of 1,000 users of Replika, published in Nature from researchers at Stanford University, found that about half of participants reported feeling decreased anxiety and a feeling of social support when speaking to the chatbot.

But other reports paint a more disturbing picture about the emergence of AI “friends”.

Last month, the Wall Street Journal reported that Meta’s AI chatbots would engage in explicit roleplay, even with underage users, when given the right prompts. Its chatbots have been designed to engage in “romantic roleplay”, intended only for older users.

Meta said the chats were “manufactured”, but that it had tightened its safeguards.

Andy Burrows, of the Molly Rose Foundation, says Meta’s decisions to rapidly launch AI bots poses a “real risk of individual and societal harm”, adding Zuckerberg’s “vision” is “disturbingly creepy” and “raises profound questions over whether it is appropriate for Mark Zuckerberg to be making these kinds of societal judgments”.

While the Stanford study suggested AI can help with mental health, other research finds the opposite. In March, a study published by OpenAI and researchers at MIT’s Media Lab suggested that there was a correlation between heavy use of ChatGPT and higher levels of loneliness.

The researchers studied 4m ChatGPT conversations from 4,000 people. The top 10pc of users felt more isolated, especially those who used the bots as an emotional crutch.

“Generally, users who engage in personal conversations with chatbots tend to experience higher loneliness,” the researchers wrote. “Those who spend more time with chatbots tend to be even lonelier.”

Farmer says: “AI companions can be remarkably unsupportive in times of crisis. There are already quite a few examples of companions providing flippant and uncaring responses to users experiencing acute mental health problems.”

Andrew Przybylski, of the Oxford Internet Institute, says so far there is little evidence that AI chatbots fuel loneliness.

“The best evidence is that it is complicated,” he says, adding “people who are lonely reach out to new technologies”.

He notes concerns may dissipate, just as they did with past panics over video games and television.

Still, Roberts, of Liverpool John Moores, is doubtful that those who turn to chatbots for friendship will feel any less isolated. “They are unlikely to lead to lower feelings of loneliness, because no matter how sophisticated the chatbots appear, it is just an AI,” he says.

Humans are social animals who rely on personal interactions to feel safe and fulfilled. “At some level an AI chatbot will always be unsatisfying and will not meet that need,” he says.

“It is not a genuine form of social connection.”

Broaden your horizons with award-winning British journalism. Try The Telegraph free for 1 month with unlimited access to our award-winning website, exclusive app, money-saving offers and more.