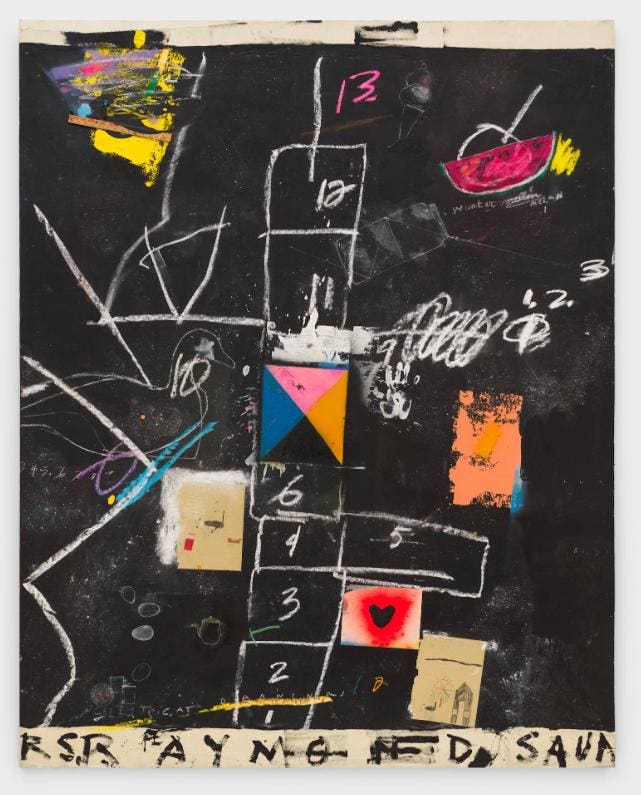

Raymond Saunders, ‘Celeste Age 5 Invited Me to Tea,’ 1986. Collection of Jill and Peter Kraus, © 2025, Estate of Raymond Saunders. All rights reserved

Estate of Raymond Saunders. All rights reserved

Visitors to the Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh are forgiven for not knowing the name Raymond Saunders (b. 1934). Eric Crosby, the museum’s director, was unfamiliar with Saunders when Crosby relocated to Pittsburgh for a curatorial job at the Carnegie in 2015, and he’s devoted his entire professional career to contemporary American art.

Saunders is hardly an unknown or a recent “discovery,” however. He was awarded a Rome Prize Fellowship in 1964, a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1976, and is a two-time recipient of the National Endowment for the Arts Awards (1977, 1984). Saunders’ paintings are in the permanent collections of the nation’s finest institutions including the Carnegie, the National Gallery, The Met, MoMA, the Whitney, and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

The Pittsburgh native’s lack of national notoriety has more to do with his remove from New York than anything else. New York and its museums and galleries and auction houses and collectors and arts media continue leading contemporary American art around by the nose. From Pittsburgh, Saunders moved to Oakland in the early 1960s.

He received an MFA from the California College of Arts and Crafts (1961) and later served there and at California State University East Bay as a faculty member. He continues living and working in the Bay Area.

Saunders also, conspicuously, had zero interest in playing the gallery game or producing art for the market. And he’s a Black man. That didn’t help any painter’s career in the 20th century.

Crosby and the Museum shine an overdue light on the artist, featuring him in their signature spring exhibition, “Raymond Saunders: Flowers from a Black Garden” (through July 13, 2025), the 90-year-old’s first solo show at a major museum and the most in-depth consideration of his practice to date.

“What struck me most, and what continues to strike me most about the work, is the degree of ambition that it holds,” Crosby told Forbes.com. “He is an artist who is a consummate student of painting, someone who has dedicated his life to the medium and embraces it in all of its complexity, all of its historical references, all of its symbolic and metaphoric illusions–so many different facets of the medium he brings to bear. I gravitate toward art that is complex and that makes me uncomfortable, that makes me ask questions, and Raymond’s work does this consistently over the six decades of his career.”

A Pittsburgh Story

Raymond Saunders, ‘Red Star,’ 1970, Corcoran Collection (The Evans-Tibbs, Collection, Gift of Thurlow Evans Tibbs, Jr.), National Gallery of Art, 2014.136.158, © 2025, Estate of Raymond Saunders. All rights reserved

Estate of Raymond Saunders. All rights reserved

Saunders didn’t spend much of his life in Pittsburgh–childhood through undergrad at the Carnegie Institute of Technology, now Carnegie Mellon University–but the years he did spend were formative. Particularly time at the Carnegie Museum of Art.

He participated in the Carnegie’s still ongoing Saturday art classes for young people. His mentor, Joseph C. Fitzpatrick, the instructor of the classes and director of art for Pittsburgh public schools, also taught Andy Warhol, Philip Pearlstein, and Mel Bochner.

The Carnegie additionally hosts one of the most prestigious and longest running surveys of global contemporary art in America: the Carnegie International. Saunders attended these exhibitions in the 1950s, gaining exposure to radical abstract painting in Pittsburgh for the first time.

“As a young man who’s learning about the possibility of painting in his own life, he’s walking through the halls of this museum seeing extreme, avant-garde painting and learning through and alongside the museum,” Crosby said. “That’s a wonderful narrative that grounds the work, that makes us presenting this exhibition different from any other museum or gallery.”

In addition to the caliber of the work, it is Saunders’ embodiment of the Carnegie’s mission that moved Crosby to not just champion, but curate the exhibition himself, a rarity for museum directors.

“As a young person, he learned how to become an artist in the halls of the Museum, learned from the Museum’s collection,” Crosby added. “This is the work of the Museum all the time, to educate young people and show them a path to choosing art in their own lives.”

The life Saunders lived has been an inspiration to Pittsburgh through the generations.

“I first came to Pittsburgh and learned quickly about the legacy of Raymond Saunders within our community as someone who excelled as a young person in the arts and then went on to have a distinguished career as an educator and as an exhibiting artist,” Crosby said. “Even though he spent relatively little time here, there is a lore about him as the successful artist who moved on from Pittsburgh. He went on to have this extraordinary career and younger artists have grown up in his shadow in Pittsburgh looking to him as a model for someone who grows up in Pittsburgh and then has a successful career in the arts.”

Saunders has never forgotten the home folks. He has titled paintings after Pittsburgh. References to the Carnegie, the Museum’s education program, the Saturday morning art classes, to Fitzpatrick, and specific artworks from the Museum’s collection feature in his paintings.

“His paintings are very situated within his autobiography and integral to that autobiography is formative time as a young person learning about art here at the Museum,” Crosby explained.

Flowers From A Black Garden

Raymond Saunders, ‘Untitled,’ 2000, The Studio Museum in Harlem; Museum purchase with funds provided by the Acquisition Committee, in honor of Nancy L. Lane, and Greater Harlem Nursing Home and Rehabilitation Center, Inc., 2022.15, © 2025, Estate of Raymond Saunders. All rights reserved

Estate of Raymond Saunders. All rights reserved

Flowers are also a consistent theme in Saunders’ paintings. He has used the exhibition title, “Flowers from a Black Garden,” to describe past exhibitions and paintings. Nearly every work includes flowers in some form.

“For me, the importance of flowers is around the possibility of beauty and love within the pictures,” Crosby said. “His work is inherently abstract, and yet, somehow beauty can take hold. The flower is something that he’s always been attracted to as a subject matter, I think, because it grows, it changes, it shape shifts, it moves through different seasons of life.”

Same as Saunders’ artwork.

“He never really had an inclination to ever finish a work, formally. He would always return to artworks,” Crosby explained. “He would come back to them, revise them, reconfigure them, add elements to them, subtract things, continue to play with the artworks and often collaborate with others and children on the making of his artworks.”

Yes, children. Throughout Saunders paintings, he’s pasted drawings by children onto the surfaces, collage style.

“There was always a process of returning back to his work rather than completing one masterpiece after another (in) linear fashion; he’d always circle back, reconsider his own practice, learn something from it, and carry it forward,” Crosby said.

These improvisations and innovations are visible across 35 works in the show, some as large as 16-feet-wide. They are filled with references to urban experience, education, Black history, pop culture, jazz, and, of course, Pittsburgh and flowers. While not overtly political at first blush, remember, Saunders was working in Oakland in the late 60s and early 70s, the Bay Area then the epicenter of the Black Power movement, the American Indian Movement, the anti-war movement.

In his large-scale works, Saunders routinely deploys a black ground recalling a literal blackboard and the ideas explored in his 1967 essay Black Is a Color, in which he claims an expansive role for the Black artist.

“i am not here to play the galleries,” Saunders writes in a personal typographic expression. “i am not responsible for anyone’s entertainment. i am responsible for being as fully myself, as man and artist, as I possibly can be, while allowing myself to hope that in the effort some light, some love, some beauty may be shed upon the world, and perhaps some inequities put right.”

More From Forbes